'Nothing could prepare you for it'

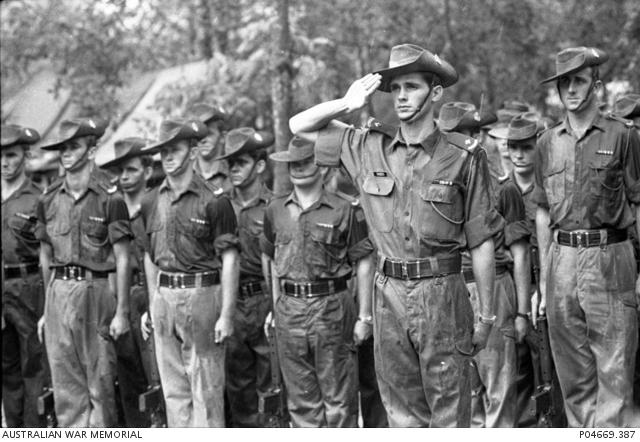

Dave Sabben receives a Mentioned-in-Despatches rosette from the former Commander of the 1st Australian Task Force, Brigadier O. D. Jackson.

Dave Sabben was a 21-year-old National Serviceman when he found himself in the middle of the battle of Long Tan, one of Australia’s fiercest and most intense engagements of the Vietnam War.

It was his first battle, and one he will never forget.

“Nothing could prepare you for it,” Sabben said. “I’d been in the army a year and a month, and to come into what was essentially a pitched conventional battle – no amount of training could prepare you for how to cope with it.

“It was the first contact – the first time that we had exchanged fire with the enemy – and there’s no baptism like a real baptism.”

Second Lieutenant David Sabben with his damaged Armalite rifle after the battle of Long Tan.

Sabben had been working as a layout artist with the advertising department of a large Sydney department store when he volunteered and was accepted for the first intake of Australia’s National Service scheme in 1965 because he saw it as his duty.

During recruit training, he was selected for officer training at the Officer Training Unit (OTU), Scheyville, NSW. He graduated as a Second Lieutenant and was posted to 6th Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR) as an infantry platoon commander. He went to Vietnam with the 1st Australian Task Force in June 1966 and was the platoon commander of 12 Platoon, D Company, 6RAR, when “all hell broke loose” on 18 August 1966.

The day had begun as an ordinary one. The men of D Company were assigned a routine patrol to continue the search for the Viet Cong forces that had launched a mortar attack on the Australian operations base at Nui Dat a day earlier and were disappointed they were going to miss a much-anticipated concert by Australian pop stars Little Pattie and Col Joye. The performers had arrived by helicopter as D company left the Task Force area at Nui Dat at about 11am, and the men could hear the sounds of the band setting up and rehearsing as they pushed through the tall kunai grass, bound for the Long Tan rubber plantation.

When they entered the plantation at about 3 pm, they had no idea that less than an hour later they would be fighting for their lives. The isolated infantry company of 108 men were all but cut off and almost surrounded. Outnumbered by at least 10 to one, they withstood massed Viet Cong attacks for three hours in torrential rain. They suffered the heaviest Australian casualties in a single engagement in Vietnam, but prevailed against the odds.

Major Harry Smith, far left, holds a briefing in the field shortly before his company return to the Long Tan battlefield. Second Lieutenant Dave Sabben is next to him.

“Two thirds of us survived, untouched, against horrific odds, but with tremendous support from everyone: the artillery, the air, the armour,” Sabben said. “It’s all part of the story, but we had not conducted combined arms operations – so [it was great] getting the APCs, the armoured personnel carriers, and getting the helicopters, and getting the artillery… We had trained a little bit with the artillery, and we could call it in with such an intensity that they fired in excess of 3,000 rounds in three hours … but that sort of intensity, we’d never trained for. Nobody in the Australian Army had even thought that that would happen.”

Sabben remembers the conditions were horrendous as the monsoon opened up and the ground became a sea of red mud.

“It was a thunderstorm, the like of which was unusual to them,” Sabben said. “Normally the monsoon doesn’t have lightning, but this was lightning and thunder, and the monsoon. The rain was coming down through the rubber canopy so hard that when it hit the earth – the red, sodden earth – it kicked up a mist, and we were lying in the mist, so it helped us … because we were camouflaged. They were up and moving, looking for us, and we were lying down in the mud and covered … so that was a help.”

Second Lieutenant Dave Sabben advances cautiously through the rubber plantation the day after the battle.

He smiles when asked if he was scared. “Sure, but you had a job to do and your mind was on the job,” he said simply. “You concentrate on what you are supposed to do, and that’s your focus, and what’s happening around you is periphery. You take notice, but you don’t let that distract you, so really it goes back to training.

"The level of our training … was of such a good standard that when action was required we slipped into it… Your environment closes around you and nothing, in my experience, nothing else matters…

“I need to know where my troops are. I need to know where the enemy is. I don’t need to know how scared I am. I don’t need to know that I need a drink of water or something. I’m totally focused on what I need here. I’ve got my map. I’ve got my radio. I’ve got my weapon if I need to fire it …

“When it’s happening you don’t realise it because you are far too busy and you are dealing with [it] moment by moment. And then when you get back the next day, [you] go back into the battlefield and see the carnage and you realise, not only, well, that could have been me, but how could such few people with such powerful support do this? And that’s the memory that comes back all the time.”

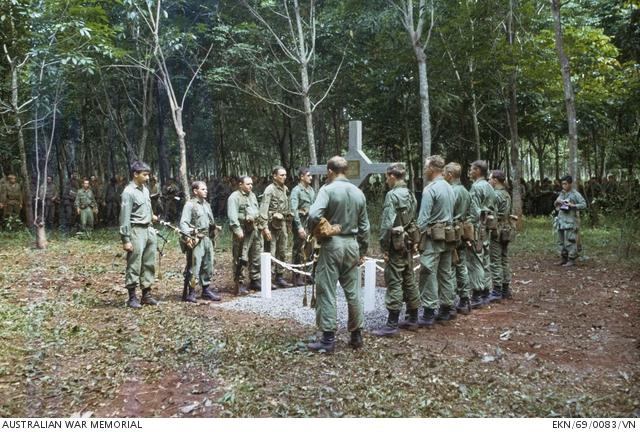

Second Lieutenant Dave Sabben reads at a memorial service for comrades of D Company who lost their lives during the battalion's tour of duty. An important part of the ceremony involved the laying and dedication of a plaque inscribed with the names of the fallen, including those killed at the battle of Long Tan.

The next morning, a combined force of infantry and armoured personnel carriers returned to the battlefield, but for the men of D Company it was a traumatic experience. The rubber plantation was a scene of utter devastation and carnage. The bodies of the soldiers of 11 Platoon who had been killed were found lying in their firing positions, still facing towards the enemy and eerily washed clean by overnight rain. Amid the horror, the men were relieved to find two of their mates who had been reported as missing in action. The men had been badly wounded, but had managed to survive the night on the battlefield.

D Company’s valiant stand at Long Tan became a defining action of the war. The Australians had inflicted heavy losses on Viet Cong forces but the cost was high: 17 Australian soldiers were killed in action and 25 were wounded. One of the wounded was an APC crewman who was wounded in action during the battle and died of his wounds nine days later. The battle had left one third of the Australian company dead or wounded, making Long Tan the army’s most costly single engagement in Vietnam.

Sabben still considers himself lucky to have survived. “When one third of your number is going to be hit, you don’t think your chances are very good,” Sabben said quietly. “If you knew you were going to drive home, and one third of the people driving home were going to be hit, you wouldn’t drive home, would you? So, yes, you do have that thought in the back of your mind, but … Long Tan was just two months after we arrived, so we had another 10 months to go, and we didn’t know how many more Long Tans there might be, so for the rest of the 10 months we were all nervous, wondering when’s the next Long Tan going to happen.”

Standing in front of his platoon on parade, Second Lieutenant Dave Sabben salutes at a memorial service for comrades of D Company who lost their lives during the battalion's tour of duty.

Sabben was mentioned in dispatches for his actions that day and later awarded the Medal for Gallantry, but the loss of his men was always a terrible blow.

“You don’t believe that it’s happening,” he said in an interview for the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. “You can see a soldier lying there and there’s a flinch and they go slack, and that’s how most soldiers are wounded. It’s not a hysterical flinging of the arms in the air and a double somersault backwards; it’s not like that at all. If he’s standing up it’s like his legs are just cut out from under him. And it doesn’t matter whether you knew him or not.

“In that split second of witnessing that, you have an image in your head. That guy, he will never hold his kids on his lap. He’ll never have a Sunday lunch with mum and dad again. You just sense the loss.”

The battle of Long Tan though was never forgotten. On the third anniversary of the battle, 6RAR – renamed 6RAR/NZ (ANZAC), with the addition of two New Zealand rifle companies – was on its second tour of Vietnam. The entire battalion returned to the battlesite to commemorate their losses in the Long Tan action and erect a cross in memory of those who died. Ten soldiers who had fought at Long Tan in 1966 stood on either side of the cross, flanked by two pipers, while the remainder of the battalion watched on.

Sometime after the communist victory in 1975, the cross was removed and reportedly used by local people as a memorial for a Catholic priest. It was later found in a hut and put on display in the Dong Nai Museum in Bien Hoa in the late 1990s.

The memorial dedication service was held on 18 August 1969 on the site of the battle of Long Tan.

Last year, the cross was gifted to Australia by the Vietnamese government and it is now on permanent display in the Vietnam Gallery at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

For those who fought in the rubber plantation at Long Tan on that day 52 years ago, it was particularly special to see the cross find a permanent home at the Memorial.

“It’s a very potent symbol,” Sabben said. “Even those who go to Vietnam rarely see the cross. In the last 10 years, I have taken one tour a year of Australian people to walk the battlefield where the replica is – and then I’ve taken them to the Dong Mai museum to see the real cross. But now, having it here, it opens up, and it makes it more accessible to 20 million Australians.

“It’s been said, probably by someone much wiser than me, that the soldiers win the battles but the politicians win the wars or lose the wars; and Vietnam was no different. The politicians sent the soldiers in. We were not very well equipped. We were not very well supported. We won the battles. We lost the war…

“There is a recognition that that simple shape represents not only Long Tan, but Vietnam.”

Dave Sabben, right, at the Memorial after the Long Tan Cross was gifted to Australia by the Vietnamese government.

For Sabben, seeing the cross always brings back memories.

“All back,” he said quietly. “I mean, it’s not a clean pristine cross, and that stain there [on the cross] is red mud – that’s how it was, that’s how the battle was…

“Three years later, the battalion put the cross there and that refreshes the memory all the time. It’s as symbolic as if you had a car accident and you retained your car, and every time you got into that same car you would remember, and that’s the same thing here. [The cross] is a constant reminder, not only of my experience, but of the company’s. One in three of the company became casualties, so it’s a memory of all those friendly faces that we lost.”

The Long Tan Cross will be on permanent display in the Vietnam Gallery at the Australian War Memorial from Friday 17 August 2018.

Join the Memorial’s head of military history Ashley Ekins and curator Craig Blanch at 3pm on Friday 17 August 2018 in the BAE Systems Theatre at the Memorial as they discuss The battle of Long Tan: unravelling the riddles and The Long Tan Cross story. This event can also be viewed live on Facebook or the Memorial’s dedicated YouTube Channel. Read Ekins’s Wartime article about the battle of Long Tan here.

The Last Post Ceremony on 18 August 2018 will commemorate Vietnam Veterans Day and the 52nd anniversary of the battle of Long Tan. The Last Post Ceremonies take place daily in the Commemoration Area at the Memorial, and can also be viewed live on Facebook or the Memorial’s dedicated Last Post Ceremony YouTube Channel.