A very close thing indeed

The battle of Long Tan was Australia’s most costly battle in Vietnam.

Australian soldiers fought in scores of fierce actions during the war in Vietnam. Few were as intense or dramatic as the actionin the Long Tan rubber plantation on 18 August 1966. An isolated infantry company of 108 men, cut off and outnumbered by at least ten to one, withstood massed Viet Cong attacks for three hours. They suffered the heaviest Australian casualties in a single engagement in Vietnam, but prevailed against the odds. Their valiant stand became a defining action of the war.

In the early hours of 17 August, the 1st Australian Task Force base at Nui Dat was shaken without warning by enemy mortar and recoilless rifle fire. The bombardment lasted just 22 minutes but it left 24 soldiers wounded and raised fears that it could be a prelude to a full-scale enemy attack on the base, established in the heart of Phuoc Tuy province just two months earlier.

Official war artist Bruce Fletcher compressed some aspects in time and embellished others: the ammunition re-supply was free-dropped from helicopters, not delivered by slung load; and the armoured personnel carriers did not use their headlights in the initial assault.Long Tan action, Vietnam, 18 August 1966, oil on canvas, 152 x 175 cm, 1970

No attack followed. At dawn, rifle companies of 6th Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR) were sent out to search for the enemy. Soldiers of B Company located the mortar base plate positions and followed several enemy tracks, but they encountered no Viet Cong. The search continued, although the threat now seemed to have passed. Companies harboured overnight in their search areas and the next day B Company sent 48 men, who were due for leave, back to the base where a visiting Australian concert party with Col Joye and Little Pattie was

due to perform.

D Company was next ordered out to search and left the base at 11 am on 18 August. Company commander Major Harry Smith recalled that he and his men were “not real happy at missing the concert” as they pushed through tall grass to the sound of the music from the base (as reported in Wartime Issue 35). The enemy, estimated to be a heavy weapons platoon of the local D445 Battalion, numbering some 30 to 40 men, was by now “thought long gone”. D Company relieved B Company at about 1pm at the edge of the Long Tan rubber plantation, 2,500 metres east of Nui Dat. After inspecting the area and a quick meal of combat rations, D Company entered the rubber plantation at about 3 pm to search eastwards. “We did not expect action,” Smith recalled, “but nevertheless, we set off in two-up formation, widely dispersed, alert, watching for the enemy.”

What Smith and his soldiers did not know was that the task force headquarters signals intelligence unit, 547 Signal Troop, had been monitoring the transmissions of a radio set belonging to the Viet Cong 275 Regiment. This highly classified signals intelligence was restricted to operations and intelligence officers and the task force commander. For the past two weeks, tracking by radio direction-finding had indicated that the radio—and with it presumably the enemy main force formation—was approaching Nui Dat from the east, advancing a kilometre every day. The transmissions had apparently ceased on 14 August, when the radio was near the Nui Dat 2 hill feature, 5,000 metres east of the task force base. Earlier patrols sent out to investigate had found no signs of the enemy in the region. Now D Company was patrolling towards the same area.

At around 3.40 pm rifle platoons had their first fleeting contacts with scattered groups of enemy. The enemy uniforms, equipment and weapons, including AK47 assault rifles, should have warned the Australians they were enemy main force soldiers, not local guerrillas, but at first “the penny didn’t drop”, Smith said.

Contacts increased rapidly and it was soon obvious that the Australians were facing a large enemy main force regiment. The Australians were used to short, sharp enemy actions in which local guerrillas quickly struck, then slipped away. But the enemy were standing and fighting, not avoiding contact, and they were massing for attack with large volumes of fire.

11 Platoon was almost surrounded and pinned down by heavy RPG and automatic weapons fire from an estimated company strength force of Viet Cong. At about this time, the monsoon broke and the battle continued through a torrential downpour. Within 20 minutes, the platoon commander and one-third of his platoon of 28 men were killed or wounded. The survivors were forced to pull back and rejoin the other platoons who were also fighting off heavy enemy attacks and manoeuvring to counter enemy flanking movements.

As the enemy continued to press their attacks, the dispersed platoons called in artillery fire support but communications were impeded as their radios were hit and damaged by enemy fire. One soldier ran forward to 10 Platoon under heavy enemy fire carrying a spare radio.

A wounded Viet Cong prisoner, one of three found on the battlefield after D Company 6RAR returned to the Long Tan rubber plantation is questioned by 6RAR intelligence officer Captain Bryan Wickens, with the help of a Vietnamese interpreter.

Major Smith managed to draw his platoons together and organise his force into a defensive perimeter around the company headquarters. Soldiers went to ground there and withstood repeated enemy attacks, including massed human-wave assaults. They held firm and controlled their fire, taking a steady toll of the assaulting enemy. Any movement by the Australians drew a furious hail of automatic weapons fire from enemy assault rifles and machine-guns and enemy sniper fire from the trees. The thunderstorm added to the deafening din of the battle, making all communication difficult.

Under intense enemy fire, the soldiers of D Company fought off successive assaults, assisted by accurate artillery fire from the base at Nui Dat five kilometres away. Labouring in acrid cordite smoke and driving rain, the gunners knew their artillery support was crucial to the infantry company’s survival. They worked hard to maintain their rhythm of preparing, loading and firing while checking and adjusting the fall of their shells in response to the calls from the forward observer in the field.Soldiers from around the base were called in to assist in unpacking the artillery rounds and feeding them to the gunners. At times, the fire of all 18 guns totalled over 100 rounds per minute. Fighter-bombers attempted to provide air support but this was found to be impossible owing to the low cloud cover and the thunderstorm.

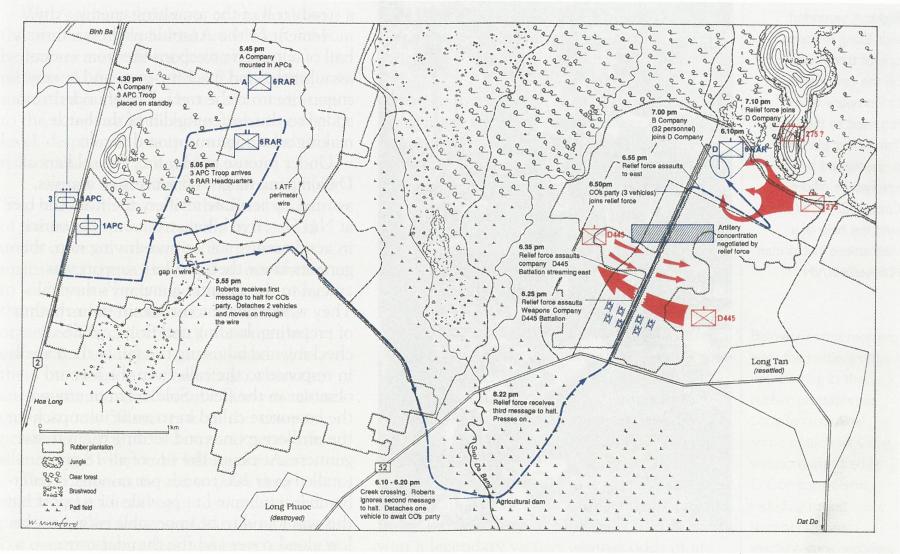

Progress of the relief force from Nui Dat to the besieged D Company in the Long Tan rubber plantation. (Reproduced from To Long Tan, by Ian McNeill, Map 15.1 - cartographer Winifred Mumford)

Meanwhile the soldiers of the besieged D Company fell back on their training and teamwork. Men know what they had to do and were sure from their training of what their mates alongside them were doing, and so worked together as a unit. As each wave of Viet Cong came forward they fired as a team, providing covering fire for each other. One soldier recalled:

A solid line of them—it looked like hundreds—would suddenly rush us. The artillery would burst right in the middle of them and there would be bodies all over the place. The survivors would dive for cover beside these bodies, wait for the next attacking line, get up and leap over the dead to resume the rush. They were inching forward all the time over their piles of dead.

Radio messages from D Company, recorded in the 6RAR log at Nui Dat, conveyed the company’s increasingly desperate situation:

4.26 pm “Being mortared . . . Want all artillery possible.”

4.31 pm “Enemy [on] left flank. Could be serious.”

5.01 pm “Enemy …penetrating both flanks and to north and south.”

5.02 pm “Running short of ammo. Require drop through trees.”

With soldiers almost out of ammunition, the artillery briefly halted fire while RAAF helicopter crews flew a daring resupply mission. At 6 pm two RAAF helicopters succeeded in dropping boxes of ammunition to the company while hovering at tree-top level, despite the heavy downpour and the risks from enemy ground fire.

Company sergeant major Warrant Officer “Big Jack” Kirby handled the distribution of the rounds to soldiers lying in the mud under constant enemy fire. Kirby was the mainstay of the defence and an inspiration to soldiers, his burly figure moving among the men as he distributed ammunition, organised the collection of the wounded, encouraged soldiers and even joked with them on occasion. At one stage, when the enemy attempted to set up a heavy machine-gun post only 50 metres from the company perimeter, Kirby moved out and personally silenced the weapon by killing the crew.

The enemy continued to press their attack and soldiers began to wonder if the promised relief force would arrive in time. For over two hours they had been fighting a ferocious battle against overwhelming odds and they were now virtually surrounded by a determined and well-equipped combined Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army force estimated at over 2,000 men. At 6.20 pm, as daylight was fading, D Company radioed to the base: “Enemy could be reorganising to attack. Two platoons are about 75 per cent effective. One platoon has been almost completely destroyed. [We] are reorganising for all-round defence.”

Annihilation seemed imminent. Then, just before 7 pm, as the enemy were apparently forming up for a final assault, the relief company of infantry, mounted in armoured personnel carriers, broke through the enemy lines and drove them off.

The battle ended and the monsoonal storm abated, as suddenly as both began. “All firing ceased as though the tap was turned off,” Major Smith recalled. Under cover of darkness, the Australian units withdrew and regrouped while the dead and wounded were evacuated by helicopters. Soldiers spent a restless night as artillery and air strikes continued to pound the battle site and likely enemy withdrawal routes.

The next morning, a combined force of infantry and armoured personnel carriers went back into the battlefield to conduct a thorough clearance.For the men of D Company this was a harrowing experience. The rubber plantation was a scene of utter devastation and carnage. The bodies of the soldiers of 11 Platoon were found lying in their firing positions, still facing towards the enemy and eerily washed clean by overnight rain. Amid the sombre scene, soldiers were elated to find two of their mates earlier reported missing in action. The two men had been wounded but survived on the battlefield overnight. Soldiers also found three enemy wounded who were treated and evacuated.

On the morning after the battle, troops in a clearing in the rubber plantation of Long Tan examine some of the Viet Cong weapons captured by D Company, 6RAR, including rocket launchers, heavy machine-guns, recoilless rifles and scores of rifles and carbines.

The grisly task of counting the enemy bodies was eventually halted at a total of 245. The dead were buried where they lay in shallow graves. There were signs that many more had been removed by the enemy as they withdrew during the night.

The bravery, tenacity and sacrifice of Australian and New Zealand soldiers at Long Tan was duly celebrated. They had won a legendary victory against odds of at least ten to one. D Company 6RAR was awarded a US Presidential Unit Citation and fifteen Commonwealth decorations were awarded to individual soldiers for their actions during the battle.

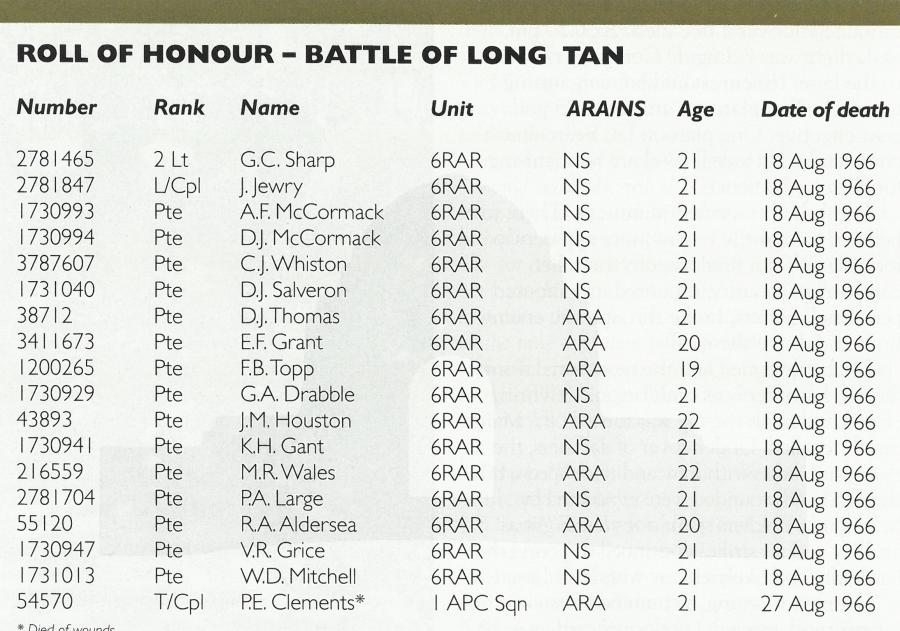

The Australians had inflicted heavy losses on Viet Cong forces but the cost was high: seventeen Australian soldiers were killed in action and 25 were wounded, one of whom died nine days later. The battle left one third of the Australian company dead or wounded, making Long Tan the army’s most costly single engagement in Vietnam. Eleven of the dead were National Servicemen and seven were Regular Army soldiers: their average age was 21 years. Brigadier O.D. Jackson, commander of the 1st Australian Task Force, was impressed by the battle performance of D Company but he judged the outcome “a very close thing indeed”. The effectiveness of the artillery support had proved crucial to the survival of the company and the relief force had arrived just in time.

Many questions remained about the enemy involved, their intentions and plans, and the outcome. It appeared that the battle of Long Tan had established the Australian task force’s dominance in Phuoc Tuy province, but that dominance did not rest unchallenged. Over the following five years, aggressive Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army forces periodically threatened the peace and stability within the province and forced the task force to retaliate.

Long Tan remains a defining event in Australia’s longest war. But it was not a pivotal battle as some have claimed. It was neither a turning point in the Vietnam War, nor was it a decisive victory. The Viet Cong units involved were damaged but not destroyed. They regrouped and continued their revolutionary struggle for nine more years until the armies of North Vietnam defeated the south in 1975.

Today, the veterans of D Company 6RAR guard the memory of their unit’s bravery and sacrifice on 18 August 1966. This is understandable. The survivors among the original Anzacs who landed on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 did the same. Just as Anzac Day has grown in significance to become Australia’s de facto national day, so too has Long Tan day become more inclusive. On Vietnam Veterans’ Day, the recalling of a single battle on one afternoon in August 1966 now commemorates all Australians who took part in that long and divisive conflict.

* Died of wounds

Suggested further reading

Lex McAulay, The battle of Long Tan (1986)

Terry Burstall, The soldiers’ story (1986)

Ian McNeill, To Long Tan: the Australian Army and the Vietnam War 1950–1966 (1993)

Bob Grandin, et al., The battle of Long Tan as told by the commanders (2004)

Lieutenant Colonel Charles S. Mollison, Long Tan and beyond: Alpha Company 6 RAR in Vietnam 1966–67 (2005)