'Treated like an outcast'

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, please be advised the following article contains names and images of deceased people.

“Coolbaroo League gives soldier hearty welcome”, West Australian, 15 November 1952.

In late 1952, Desmond Parfitt attempted to order some sandwiches from a shop in the West Australian town of Williams. Despite the fact that he was wearing his uniform and service medals, he was refused service and “treated like an outcast”.

“Lance Corporal Parfitt in my opinion should have gone to the police station,” wrote an outraged letter writer at the time, “and the shopkeepers might have learnt something.”

An Indigenous soldier from Western Australia, Parfitt had appeared regularly in the newspaper columns in his home state.

One article noted that, “When [eminent English philosopher] Bertrand Russell was in Perth some time ago he met Parfitt at the Bassendean camp and he was most impressed with him.”

But when Parfitt returned to Australia from Korea, having been wounded in action at the battle of Maryang-San, he faced the same discrimination as before.

Michael Bell, the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Australian War Memorial, said Parfitt’s story was all too familiar.

“Despite lack of recognition of rights, denial of citizenship, and concerted efforts at exclusion, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have served in conflicts involving Australian defence contingents since Federation,” Bell said.

“When the First World War broke out in 1914, many who tried to enlist were rejected on the grounds of race; but many slipped through the net.

“They served on equal terms and were paid the same rate as non-Indigenous soldiers, but when they returned home, they found that discrimination had worsened.

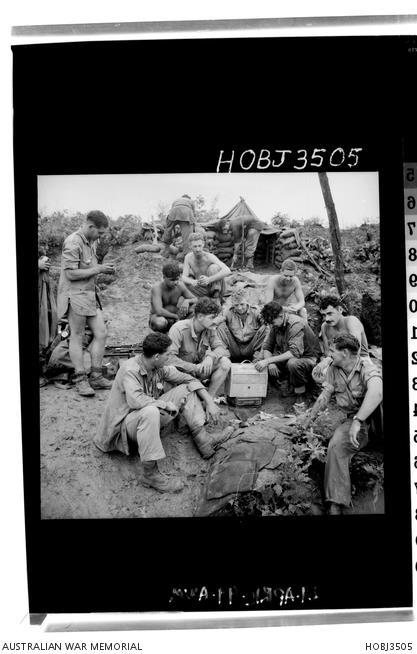

Korea. c. August 1952. Soldiers of C Company, 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR), listen to their new radio. A shirtless Desmond Parfitt is upper left of centre.

“As late as 1928 Indigenous Australians were being massacred in reprisal raids, while protection acts had given government officials even greater control.

“When the Second World War broke out, Indigenous Australians and Torres Strait Islanders were allowed to enlist and many did so, but in 1940 the Defence Committee decided the enlistment of Indigenous Australians was "neither necessary not desirable", partly because they believed white Australians would object to serving with them.

“When Japan entered the war, however, the increased need for manpower forced the loosening of restrictions and thousands of Australian Aboriginals enlisted and served.”

The first Indigenous serviceman to be promoted to a commissioned rank was Reg Saunders, whose family had a strong tradition of service. The son of a First World War veteran, Saunders fought in the Second World War in the Middle East and New Guinea, and then returned to the army for the Korean War, serving as a captain in the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment.

Desmond Parfitt was one of the men who served in Saunders’ C Company.

Parfitt’s father had served during the Second World War, and Parfitt followed in his footsteps, enlisting at the age of 21 and serving in the Korean War.

He was wounded in action at the battle of Maryang-San in October 1951, and spent a month in hospital before returning to active service.

Newspaper reports at the time noted that the Parfitt was “treated like an outcast” when he returned to Australia and that he deserved better.

“Again, those who had fought for their country came back the same discrimination as before,” Bell said. “Barred from Returned and Services League clubs, many would not be given the right to vote for another 17 years.”

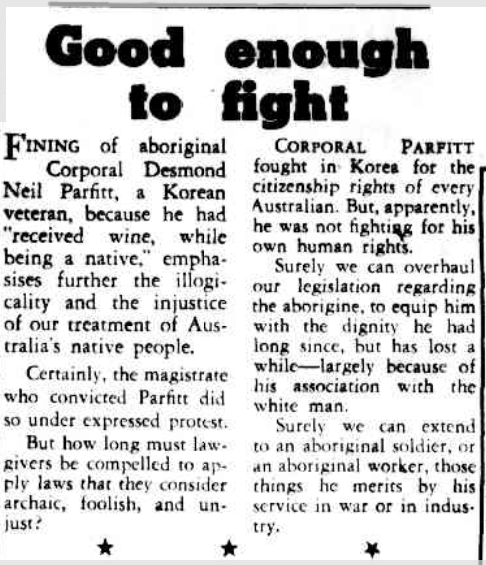

The Argus, 22 January 1953.

Other responses, however, were less sympathetic.

“What’s wrong with you city people?” one man fumed in the papers. “You get all het up when any of us country folk put our coloured brothers in their place … Why should our white waitresses and proprietors demean themselves if it is against their principles? … These coloured people hate honest work and all this crawling to our poor black brother is creating a feeling of superiority in the native for which we country people have to pay dearly … Once you have experienced the laziness, deceitfulness and dishonesty of our semi-civilised natives you would have a very different opinion of the subject.”

In 1953, Parfitt was again the centre of controversy when he was found guilty of having “received wine, while being a native”.

“The magistrate who convicted Parfitt did so under expressed protest,” Bell said. “And newspaper articles ridiculed the notion that Parfitt could be considered good enough to fight for his country, but be unable to buy a beer.”

The Argus argued the judgement emphasised the “injustice of our treatment of Australia’s native people”.

“How long must lawgivers be compelled to apply laws that they consider archaic, foolish and unjust?” the Argus asked.

“Corporal Parfitt fought in Korea for the citizenship rights of every Australian. But, apparently, he was not fighting for his own human rights.”

“These same newspapers also revealed the level of discrimination that still existed,” Bell said.

One correspondent wrote that “‘original Australians’ to which race Parfitt belongs by birth, are more than ordinarily quarrelsome under [alcohol’s] influence and are better citizens without it … This is for their own and society’s protection.”

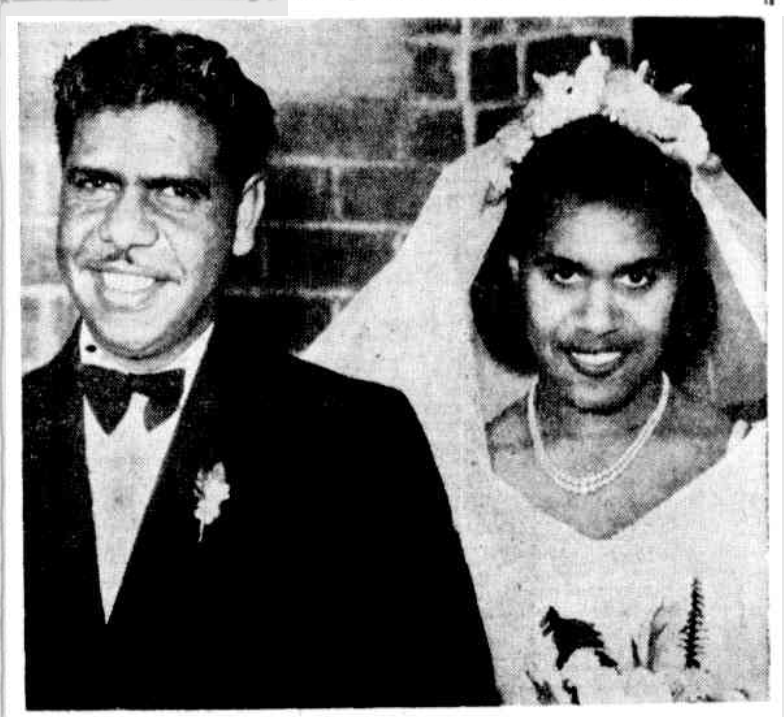

This was brought to the fore after Parfitt married Phyllis Narkle at St Joseph’s Church in Bassendean later that year.

“While newspaper pictures portray a happy picture of the newly-wed couple, their honeymoon was less than joyous,” Bell said.

Des Parfitt and Phyliss Narkle. Mirror, 17 October 1953.

“A flat that they thought had been arranged for was unavailable,” the local newspaper reported.

“Accommodation sought around hostels and other places for them was just not to be had. The truth is that when it was found they were aborigines, accommodation was denied them. Finally, as a great favour, they were allowed to stay one night in a city room provided they did not appear for breakfast next morning.

“Disappointed and doubtless disillusioned they had to forego the week’s honeymoon they had planned in Perth and left for the country.”

The newspaper article that detailed these events apologised and expressed embarrassment, but it also insisted that “no reasonable critic disputes our White Australia Policy”, and ruled out the concept of “the marriage of black and white and the mixture of the races”.

“By the time that Des Parfitt died on 18 October 1996, Australian society had changed,” Bell said.

“The White Australia policy had been dismantled, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were no longer prevented from entering the Australian Defence Force.”

A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, Bell is researching the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent and is working to identify Indigenous Australian soldiers who have served and are currently serving.

“Today, the Australian Defence Force looks to recruits through the Defence Indigenous Development Program, and the actions and involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in all Australian conflicts since Federation is far better known,” Bell said.

“But while many Australians assume that the sorts of discrimination faced by Des Parfitt is a thing of the distant past, it doesn’t take much searching to stumble across similar sentiments on social media.

“One of the antidotes to this problem is to learn and tell the many stories of Indigenous service, of those who rose above to fight for the nation that spurned them – ‘those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.’”

Michael Bell is working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au.

The Memorial's touring exhibition For Country, for Nation is on now.