An enduring hope

When Ethel Freeth was told that her son had been killed during the Second World War, she refused to believe it.

Her son, Flight Sergeant John Freeth, was killed when his plane crashed off the coast of Scotland in May 1943, but she was convinced that he had survived the crash, and spent years lobbying officials to find out what had happened to him.

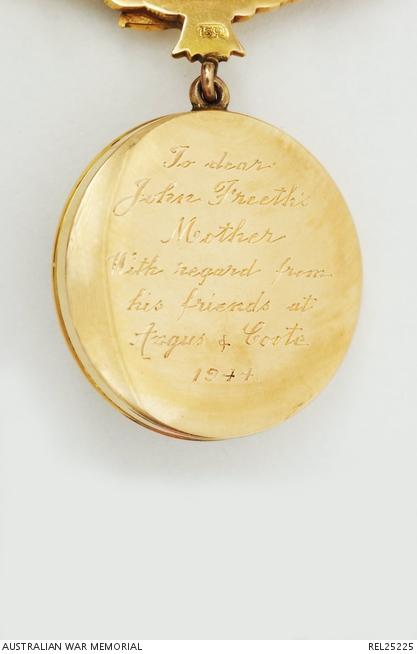

John had been a jewellery salesman at Angus and Coote before the war, and his colleagues created a beautiful gold brooch in his memory for her. They hoped it would help her come to terms with her son’s death, but she refused to believe it, and never gave up hope of finding him alive.

Ethel’s brooch is now on display at the Australian War Memorial as part of the After the war exhibition.

The exhibition explores the consequences of war through personal stories of love, loss, and hope from the First World War to Afghanistan.

For assistant curator Dr Kerry Neale, Ethel’s story is particularly poignant.

“War alters the lives of almost everyone it touches, from those who served to the loved ones left behind, and its ripples effects can continue to affect people generations on,” Dr Neale said.

“Mrs Freeth refused to believe that her son had died to the point that right into the 1950s she was writing to the Prime Minister, to the Minster of Air, and to the Air Ministry.

“There was even a story in the papers where she looked at a photograph and thought that it was her son, and what we’ve got is the letter from them saying that we need to explain to her that we know who the man in the photograph is, and that he will come and speak to her if need be to prove that he’s not her son.

“She just could not believe that her son had died. She was adamant that her son had amnesia and was living out a life somewhere, unaware of who he was, and she kept to that belief until her death in 1971.”

Ethel Freeth with her son John in Sydney.

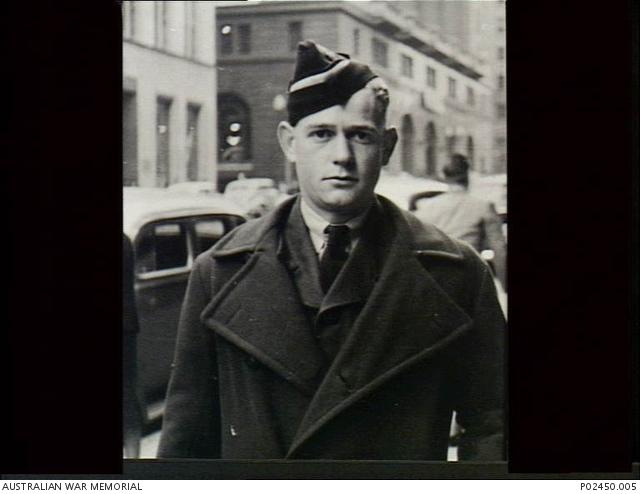

John Freeth enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force on 25 May 1941, two days after his 21st birthday.

He and his mother posed for a final photograph before he left for Canada with the Empire Air Training Scheme.

“It was probably one of their final outings as mother and son; him in his uniform and her so proudly standing beside him,” Dr Neale said. “You can see that there’s that sense of pride of a new officer wearing his uniform, and that love and pride in his mother’s faces as well.”

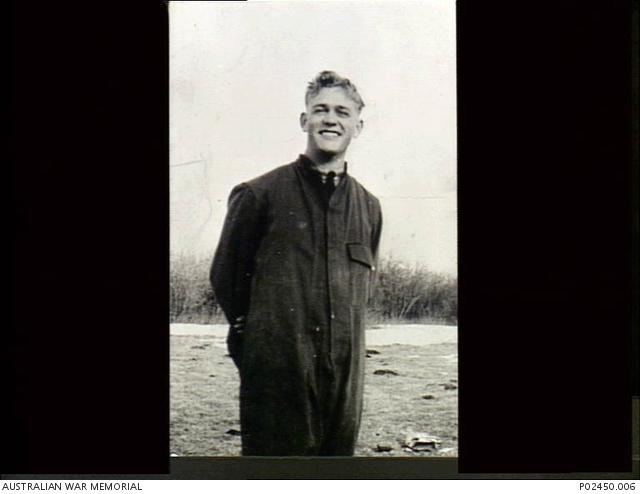

John was posted to Britain in late 1942 and joined 455 Squadron in Scotland in early 1943. Equipped with Handley Page Hampden torpedo bombers, 455 Squadron flew anti-U-boat patrols with RAF Coastal Command over the Norwegian Sea.

In April 1943, John and his crew attacked and sank the German U-boat 227 off the Norwegian coast with eight depth charges. It was considered to be an outstanding achievement as the crew members were untrained in the difficult skill of anti-submarine attack. Despite being hit by machine-gun fire, the crew escaped unharmed. But John’s luck did not last.

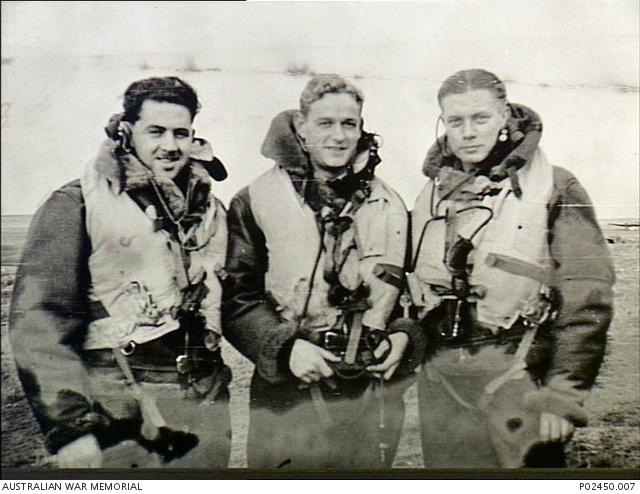

An informal portrait of John Freeth, centre, with Bert Downing and Bert Wheatcroft in Scotland in 1942.

Less than a month later, John was killed when his Handley Page Hampden torpedo bomber collided with a Bristol Beaufighter from 235 Squadron during an exercise off the coast of Scotland.

“It was just a day after his 23rd birthday,” Dr Neale said.

“The aircraft went down with John and his crew, and all four men died instantly. Only two bodies were recovered and unfortunately John … was lost at sea.

“It was almost two years to the day that he enlisted that he was reported missing, presumed dead.”

His body was never recovered, and his mother refused to believe that he had died, insisting that he must be alive somewhere suffering from amnesia.

Ethel spent years writing to her local MP, the Royal Australian Air Force, the Air Ministry, and even Prime Minister Ben Chifley insisting that her son had survived the crash and just needed to be found.

She ended a letter to the RAAF in 1945 about her son’s personal effects saying: “Trusting you will understand my persistence in believing that my darling son will eventually come back to me. Please put yourself in my place. What would you believe under the circumstances?”

An official later noted: “The evidence that Flight Sergeant Freeth lost his life in an aircraft accident in the UK in May 1943 is conclusive, but Mrs Freeth is one of numerous mothers who will not accept evidence, and she has since 1946 approached the former Prime Minister and the Minister for Air on the matter.”

She became even more convinced that her son was alive when she saw an article in Sydney’s Daily Mirror in December 1946 about two RAAF pilots who had broken a trans-Tasman record by flying a Mosquito aircraft from Mascot, Australia, to Auckland, New Zealand. Ethel was certain that a photograph of one of the pilots, Flight Lieutenant Leonard Lobb, was actually of her son John.

“She is sure that the blue-eyed, blond-haired man who is in these photos is her boy,” Dr Neale said.

“She actually writes in wanting confirmation that Flight Lieutenant Lobb is her son and that he has simply been misnamed or has been living another life…

“They have to provide her with evidence and confirmation from Flight Lieutenant Lobb himself, who says to her, ‘I’m sorry, but I’m not your son, and here is my story,’ and even then, I think, Ethel was not convinced.”

She simply refused to give up hope, and in August 1949, she appealed to the newspapers directly to help find her son and give her “peace of mind”.

Nothing, it seemed, could convince her that her son had died during the war, and she continued to contact officials into the 1950s.

“Mrs Freeth called again,” an official wrote. “She is still of the opinion that her son is alive. I explained to her the details of the crash and endeavoured to convince her that there could be no doubt that her son was killed and that it was impossible that he had taken part in a flight in 1946 under the name of Flight Lieutenant Lobb. She remained unconvinced but did not ask for any action to be taken and departed saying that God in his own time would reveal the true facts … There appears to be no possibility of convincing her that her son is dead.”

John’s colleagues created the stunning gold cameo brooch in his memory, hoping that it would help her come to terms with his death and give her solace.

It is engraved on the back with “To dear John Freeth's Mother with regard from his friends at Angus and Coote, 1944” and features a hand-coloured miniature of a black-and-white studio portrait that was taken in London not long before he died.

“We don’t know for certain, but I would think she would have worn it almost every single day,” Dr Neale said. “It’s an absolutely stunning example of what we refer to as sweetheart jewellery… where pieces were made to be worn by the mothers, the girlfriends, and the wives of those men who were serving overseas as a memento, and a reminder of their loved ones.”

Ethel treasured the brooch for the rest of her life.

“It’s one of those pieces that really speaks to you,” Dr Neale said. “You can really see the love that she had for her son, the fact that she could not accept his death, and that even his friends at the jewellery store wanted to give her some sort of closure by having this made for her.”

Ethel died on 9 April 1971, still believing her son was alive.

“We are talking about a mother’s love and a mother’s loss,” Dr Neale said.

“It’s about trying to come to terms with the grief that you experience when people die on a distant shore and you don’t even know the circumstances around their death or even where they are buried. It’s a way of harnessing that grief and emotion into an object that can become a bit of a memorial to that lost love …

“With Ethel’s story you almost see an enduring hope as well. She would rather live her life with the belief, and the hope, that her son had amnesia and was living a fulfilled life somewhere.

“His work colleagues had crafted this beautiful brooch in memory of her son to try and give her some sense of closure, but right until her death, she would not believe, and could not allow herself to believe, that her son had died.”

The After the war exhibition runs until October 2019. For more information, visit here.

Listen to Louise Maher’s podcast, A mother's love and memory, here.