Remembering the Hilliet brothers

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people please be advised that the following article contains the names of deceased people. It also includes examples of racist and offensive language that were in use at the time.

George and William Hilliet were prepared to sacrifice everything to serve their country. But when the two brothers volunteered to enlist during the First World War, they were rejected because of the colour of their skin.

The Hilliet brothers were among more than 1,100 Indigenous Australians known to have enlisted or attempted to enlist during the First World War despite restrictions in place to prevent them from doing so.

For Michael Bell, the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Australian War Memorial, the story of the Hilliet brothers and their struggle to fight for their country is particularly confronting.

A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, Bell has been researching the military service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent, and is working to identify Indigenous Australians who have served or are currently serving.

He said the story of George and William Hilliet was a powerful one, a permanent reminder of the racism Aboriginal people faced as they fought to serve their country.

“George and William were two brothers from Victoria who tried to enlist during the First World War,” Bell said.

“They were living on Cummeragunja Mission, which was one of the largest Aboriginal missions in the area, just over the NSW side of the border, on a bend on the Murray River, when they went to enlist in Berrigan in January 1918.”

The 1903 Defence Act, which was amended in 1909, had exempted people who were not “substantially of European origin or descent” from enlisting. But in 1917, after the first conscription referendum was defeated, and with large numbers of Australian casualties in Europe and the need for more manpower due to the ongoing war of attrition in the trenches of the Western Front, Military Order 200 was issued. It stated “half-caste” Aboriginal men could enlist in the AIF, provided the examining medical officers were satisfied one of the parents was of European origin. All previous instructions on the subject were to be cancelled.

“It’s often referred to as the ‘half-caste law’ or the ‘half-caste order’,” Bell said.

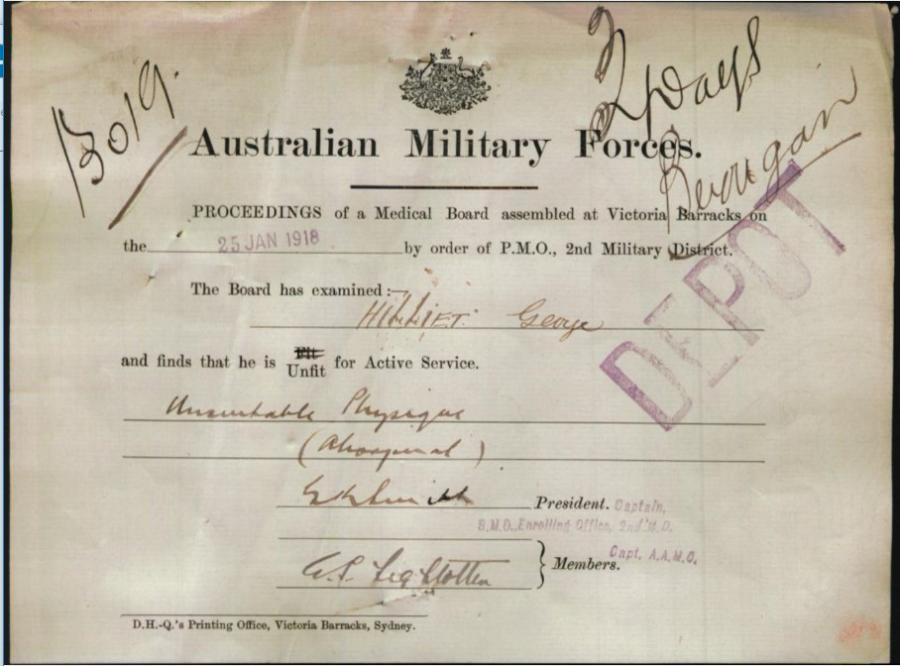

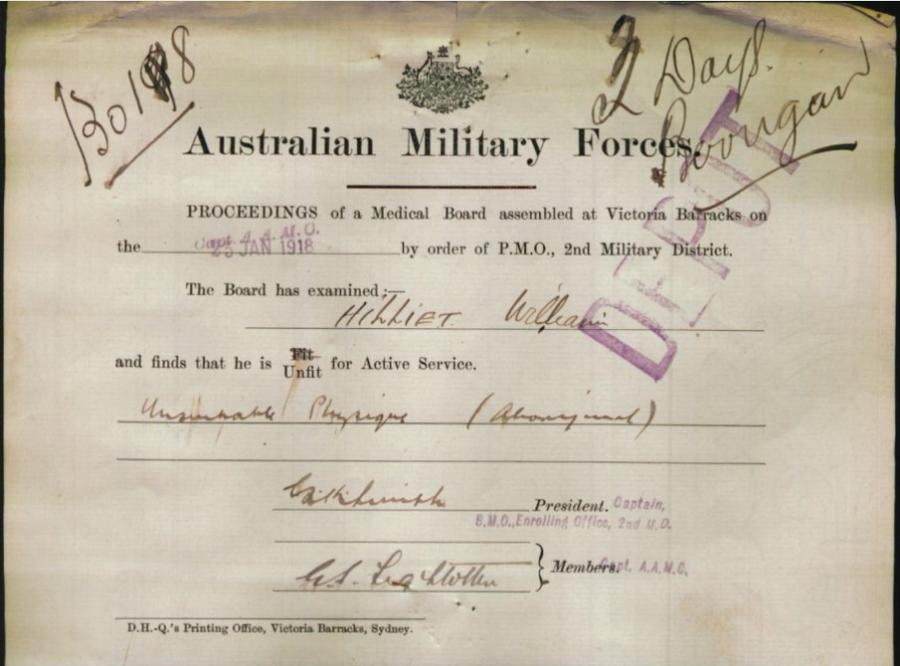

“But when George and William Hilliet tried to enlist on the 25th of January 1918, nearly a year after the ‘half-caste rule’ came in, they were found unfit by the medical board. Their reasoning was ‘unsuitable physique’ and in brackets, ‘Aboriginal’.

“It’s a clearly defined record that shows they were rejected based on their race.

"Instead of saying they were ‘irregularly enlisted’, or using any of the other euphemisms that were around at the time, they’ve rejected two fit, healthy young men – fit, healthy young men in all other circumstances, except the colour of their skin – and the doctor’s put his name to it, and then signed it, stating the reason they were rejected was because of ‘unsuitable physique’, and that ‘unsuitable physique’ was because they were Aboriginal.

“Despite the ‘half-caste law’ coming into place, it was still a common practice, even in the final year of the war, to reject Aboriginal men based on the colour of their skin, and there is no clearer example of this than being told that you are unfit for active service – Unsuitable Physique (Aboriginal.)

“That’s the most powerful interpretation, and it cannot be confused, that you get rejected simply because you are Aboriginal.”

Today, the Hilliet brothers are included on the Memorial’s First World War Indigenous Service List.

For Michael, it’s important that their story is not forgotten.

“You’ve got young Aboriginal men who want to enlist and fight for their country, and this is how they were treated,” he said.

“There’s no greater patriotic deed that you can commit to or ask for than to put your life on the line to go and defend your country and these men are being rejected because of their race.

“They are seen as ‘less than’, and it’s important that we highlight these stories, and tell people about them.

“They still wanted to serve. They still wanted to do their bit.

“And then to be told your services aren’t required because you are Aboriginal, when they’re crying out for men, there’s no clearer statement than that.

“And that’s why it’s important to tell these stories.

“It’s about the fight within the fight... and the willingness of our men to go and fight for a country where they weren’t entitled to the rights that they were fighting for.”

Michael Bell is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Australian War Memorial. A Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, he is trying to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of any person of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who served, or is currently serving, or has any military experience and/or contributed to the war effort. Michael would like to get further details of the military history of all these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au

For more information about Indigenous service, visit here.