Harry Aldridge: Navigating Bomber Command

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people please be advised that the following article contains the names of deceased people.

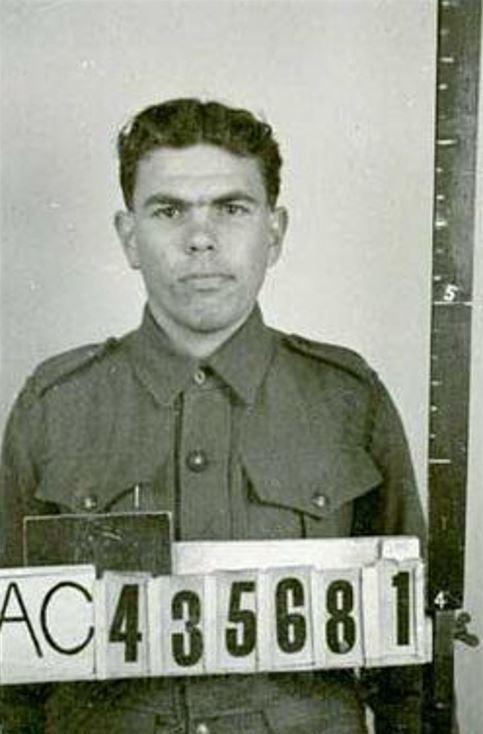

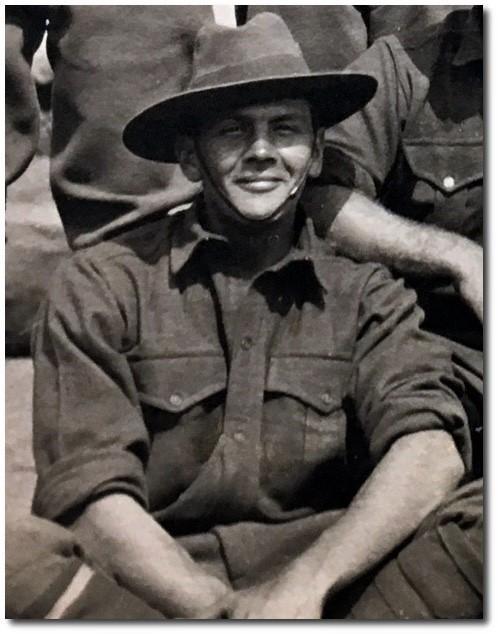

Harry Aldridge, a Butchulla man from Pialba on the Fraser Coast of Queensland, serve as a navigator with Bomber Command during the Second World War. Photo: Courtesy National Archives of Australia

Flight Sergeant Harry Aldridge was huddled over a small desk in a Lancaster bomber, flying low over the Netherlands.

Sitting in a cramped, curtained-off compartment, he worked by the light of a simple lamp, the pilot relying on him to find the target before guiding the aircraft and its crew safely home.

He was one of the busiest men in the Lancaster. As a navigator, he had to be highly-skilled and adaptable, maintaining a high-level of concentration for virtually the whole flight, plotting a course and making last-minute adjustments if the weather changed, or if the Lancaster came under attack. His tools were not bombs or machine-guns, but charts, protractors, dividers, rulers and pencils.

But this mission was different.

On the 29th of April 1945, 242 Lancaster bombers flew to six different parts of the Netherlands. Rather than releasing bombs over their targets, they would be dropping food.

Mildenhall, RAF Station, Suffolk, England, May 1945: Crew members of No 15 Squadron RAF with a trolley load of food, ready to be loaded aboard a Lancaster bomber and dropped in the Netherlands as part of Operation Manna.

It was during the last days of the war in Europe, and the Allies had devised a plan to deliver food by air to alleviate the suffering of the Dutch in what would be the first airborne humanitarian mission.

German occupation and the consequences of the war in Europe had left the Netherlands without food or supplies; and the Dutch were starving, having already endured the horrific famine known as the “Hunger Winter” of 1944–1945.

On that first mission, Allied bombers dropped almost 535 tons of food; Dutch civilians running from their homes to wave to the bombers as they rumbled overhead.

Operation Manna – named in reference to the Biblical account of God dropping bread from heaven for the starving Israelites – had begun.

Over ten days, RAF bombers would drop more than 7,000 tons of food; it was the first time combat aircraft had been used for humanitarian purposes.

Harry, pictured left, during the war. Photos: Courtesy Ann Rutledge

Among those taking part was Harry Aldridge, the first navigator in Bomber Command to be identified as having Aboriginal heritage by researchers at the Australian War Memorial.

A Butchulla man from Pialba on the Fraser Coast of Queensland, Harry had enlisted in the army in 1942 before transferring to the Royal Australian Air Force in 1943.

His family was well-known in the local area and had a proud history of military service; his father and uncle had served on Gallipoli and the Western Front during the First World War.

Harry’s grandmother was Lappy “Wondunna” Tanner, a Butchulla woman, whose people are the traditional owners of K’gari (Fraser Island).

Her parents' identities remain a mystery. Earlier research had suggested Lappy could be the daughter of Mary Ann Dalungdalee, a Dalungbara woman, who had been born at Woolgoolba Creek on Fraser Island. She was married to John Rooney, an Irishman who had emigrated to Australia with his brother Jacob in 1863. The brothers had successfully tendered to build the Sandy Cape Light House on Fraser Island, which was completed in 1869 with the help of local Aboriginal people. Mary Ann and John married that same year; their wedding was reported as being in the Indigenous tradition, with John “exchanging the customary gifts with the elders”.

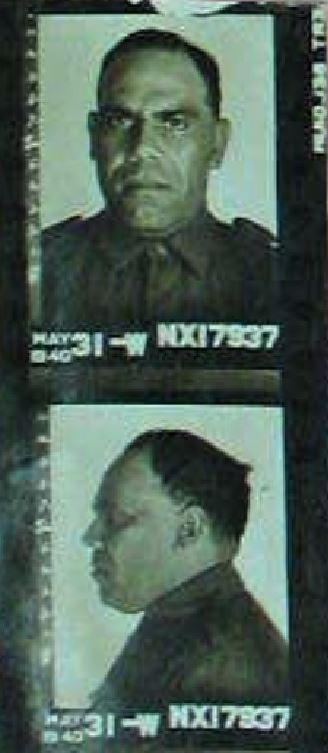

Their daughter Susie married Robert Dow, an indentured cane cutter from Ambryn Island. The Aboriginal Protector had signed a special permit allowing them to marry on 11 March 1905, and they married 11 days later. Their son Alfred would go on to serve with the 2/1st Pioneer Battalion during the siege of Tobruk.

It has been suggested in the past that Lappy could have been Susie's older sister. Lappy was known as Lappy Tanner or Lappy Goodwin. The surname Goodwin was from a well-known family in Maryborough. The surname Tanner may have come from the Reverent Tanner, who is said to have taken Lappy from the Mount Perry Mission to work in the house of Maria Aldridge.

Lappy went on to marry Harry’s grandfather, Harry Edgar Aldridge, in November 1898. His father, Edgar, was reportedly the first white man to settle in Maryborough, with Harry Edgar being the first white baby born in the area. The couple married in New Zealand, possibly because they did not obtain permission from the Chief Protector of Aboriginals to marry in Australia. They had two daughters, Essie and May, and two sons, Harry’s father – also called Harry Edgar – and Harry’s uncle – Daniel Edgar. Their births were registered twice, possibly to ensure they were recognised as Harry Edgar's children.

Although discriminatory policies at the time sought to exclude those “not substantially of European origin or descent” from enlisting, Harry’s father and uncle served during the First World War.

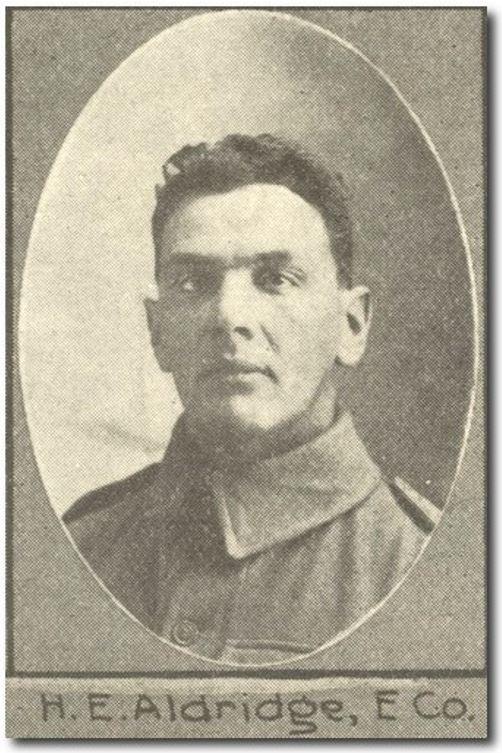

Harry Edgar Aldridge was the son of Harry Aldridge and Lappy Tanner, a Butchulla woman, whose people are the traditional owners of K'gari (Fraser Island). He served on Gallipoli and the Western Front during the First World War.

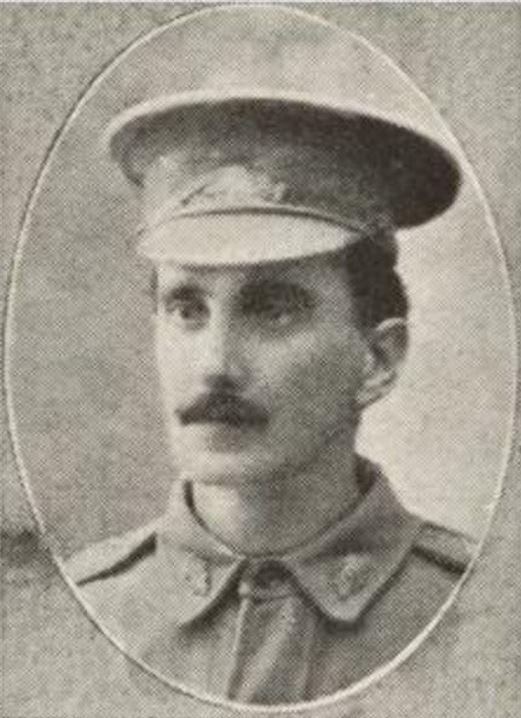

Daniel Aldridge also served during the First World War.

Harry’s uncle, Daniel Edgar, enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in March 1916. He served on the Western Front with the 31st Battalion, and returned to Australia in May 1918, suffering from trench fever.

His father, Harry Edgar, had enlisted within weeks of the declaration of war. He was allotted to the 9th Battalion and embarked for Egypt in September 1914.

Admitted to hospital with pneumonia days before the landing on Gallipoli, Harry Edgar was evacuated to Cairo where he spent two months recovering. He rejoined his comrades in July and served on the peninsula for the remainder of the Gallipoli campaign, leaving just short of the evacuation in December to be treated for jaundice. He was transferred to the newly-raised 49th Battalion in Egypt and went with it to France, where he was wounded in the right leg at Mouquet Farm on 3 September 1916.

He was evacuated to England for treatment, but contracted rheumatic fever while his leg healed, and was deemed no longer fit for military service, returning to Australia in February 1917.

Harry, named Harry Edgar like his father and grandfather before him, was born in Maryborough, Queensland, in October 1922.

An assistant teacher at Cordalba, he joined the Citizen Military Forces in June 1942, enlisting in the Second Australian Imperial Force a month later. He discharged on 5 July 1943 to join the RAAF, enlisting the following day. He went on to train as a navigator as part of the Empire Air Training Scheme in Canada before heading to the United Kingdom to join Bomber Command.

In April 1945, Harry transferred to RAF Squadron 622, stationed at Mildenhall, where he became part of a tight-knit crew of three RAAF and four RAF personnel flying Lancaster bombers.

As well taking part in Operation Manna, Harry and his crew were involved in Operation Exodus, repatriating former prisoners of war from Europe to Britain.

Harry was discharged after the war in September 1945 and settled in Brisbane where he worked as a federal public servant for the Australian Taxation Office. When he retired, he returned to Hervey Bay at Scarness, living not far from his mother's house. He died at Hervey Bay in November 1995, aged 73. His ashes were interred in the Aldridge family vault in Maryborough cemetery to lie with four generations of the Aldridge family, including Harry Edgar Aldridge and Daniel Edgar Aldridge. None of them ever never spoke about the First or Second World Wars.

Harry's story is one of the many being shared by the Memorial’s Indigenous Liaison Officer, Michael Bell.

“While Harry Aldridge is the first navigator in Bomber Command to be identified as having Aboriginal heritage, he was by no means the only one serving in Bomber Command – or even in RAF Squadron 622,” he said.

“His story is significant because it represents the expanding research and knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander service.

“He’s now one of 16 Aboriginal men we’ve identified as being part of air crew in Bomber Command during the Second World War, but more significantly than that, he is our first navigator.

“We’ve known about the service of Aboriginal pilots, but with Aldridge, we’re now starting to fill out the stories of the rest of the aircrew.

“His family’s long history of service, through his uncle, and his father on Gallipoli and the Western Front, is reflective of what we’ve been saying here at the Memorial, that there has been a long and broad history of service of Aboriginal people in the defence of Country.

“It’s continued right through his family, and it’s the little known histories of our men in the Second World War that we are working to uncover.

“Through further research, and assistance from community members, and our veteran community, we are starting to identify, and share these stories.”

Harry Aldridge, pictured front row, second from left.

Harry in 1943. He is pictured fifth from the left in the second row. Photos: Courtesy Ann Rutledge

A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, Bell has been working to identify Indigenous Australian soldiers who have served or are currently serving. He hopes others will come forward with their own family stories.

“What we’re trying to do is appeal to all the families of the people who have served,” he said.

“Your story is important as well. It’s not just the gong winners, or those on the Roll of Honour.

“It’s the everyday service of people, and the differing roles our men and women have played.

“Being a navigator, Aldridge would have been under immense pressure.

“The navigator is guiding the whole crew, and it’s about getting the mathematics right, and getting the crew there and back safely.

“You don’t want to make a mistake; the lives of the crew are in your hands.

“We didn't know a lot about what happened to Aldridge after the war until members of his family got in contact.

Alfred Dow was one of the famed Rats of Tobruk. Photo: Courtesy National Archives of Australia

“We’re trying to find out further details from all the families, so we can tell the bigger picture.

“We want to try and understand why they served, what happened to them, and how their service affected them, so we’re searching for all those answers from the families … What they were like before they went to war, and what they were like when they came home.

“It’s about understanding the man and the family, as opposed to just the soldier, or the pilot, or the navigator in this case.

“It’s about understanding the full impact of military service, but also the full impact of the political policies and the treatment of Aboriginal people of the day and how those combine.

“It’s about putting the Indigenous face into the Anzac legend, and giving our men and women the recognition they didn’t get at the time.

“We’re not just looking for the first, or the best and the bravest, or the hero; we’re looking to reflect everyday service from different families from different places and different backgrounds.

“We don’t want to forget about our Tasmanian brothers and sisters, or our Western Australian brothers and sisters … we want them to know we’re interested in their stories as well.

“It’s about remembering and paying respect – the dignity of putting a name to an unknown face in a photo, the dignity of sharing their wartime experiences with the family. But it’s also about making sure we’re a culturally safe place to be able to accept these stories from the community in a safe and culturally appropriate way.

“It’s an honour to do it, and the joy I get in bringing these stories to light, is the fact that our veterans are now encouraging the modern, younger veterans, to come forward and tell their own stories as well.

“It is a little known story that deserves to be widely known.”

Private Harry Aldridge served with the 9th Infantry Battalion during the First World War. Photo: Courtesy State Library of Queensland (Warnes Family Collection 2.31166)

Michael Bell is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial. A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, he is working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au