Australians in the Atomic City – BCOF interactions in Hiroshima

On 6 August 1945 the United States Army Air Force dropped the first atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. The effects were devastating. The bomb released energy equivalent to 12.5 kilotons of TNT and had a surface temperature of 6,000 degrees. It is estimated that approximately 30% of the population, between 70,000 and 80,000 according the US Strategic Bombing Survey, died as an immediate result. The radius of total destruction was 2 km, demolishing the landscape and reducing the city to rubble.

Hiroshima on 28 February 1946. Looking south from the centre of the city, it shows only a section of the damage caused by the bomb.

In March 1946, Australia was assigned to Hiroshima and the surrounding area as part the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), whose mission was to demilitarise and democratise Japan. By 1946 there were already the beginnings of a major tourism industry in Hiroshima and, unaware of the dangers of radiation, Australians flocked to the infamous city. Locals sold debris to tourists as a way of survival, while other visitors sifted through the rubble to take home a souvenir. The Australian Military History Section was also interested in salvaging this material as historical records.

Melted beer bottle collected by Lieutenant Allan Queale, head of the Military History Section, from beneath the epicentre of the bomb. Relics such as this were chosen for their melted state rather than their cultural significance.

A portion of a terracotta tile fused by the atomic blast with other debris, including pottery. This was also collected by the Military History Section as a war relic to be sent back to the Australian War Memorial.

Tours for high-ranking government and military officials were also extremely popular, as well as important in understanding the evolving nature of warfare. From a military technology perspective, there was an intense fascination with effects of this bomb, rather than the average sightseer’s interest in the novelty of the site. In addition to viewing the damage wrought on the buildings and infrastructure, many tours included visits to nearby hospitals in order to meet bomb victims and inspect their injuries.

Lieutenant General Sir Horace Robertson, Commander in Chief of BCOF, in front of the infamous a-bomb dome in 1947. At a peace ceremony in 1948 Robertson told the crowd of Allied officials and Hiroshima residents, “The destructive ways of war and aggression brought this upon your city.”

Hiroshima evoked a range of responses in Australian servicemen and servicewomen. The fear of Japanese expansion, as well as racial prejudice, had been present in Australia since the beginning of the 20th century. The atomic bomb was seen by many Australians who had served in the Second World War as a morally justifiable action in forcing the Japanese surrender. They had experienced firsthand the scale of horrific physical and psychological injuries inflicted by Japanese forces on the battlefield and in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps. This overwhelming exposure to violence and suffering of their countrymen and women made it difficult to empathise with the suffering of their longstanding enemy.

In a survey done by BCOF as part of an intelligence summary in February 1947, it was noted that there was an overall “lack of feeling for the sufferings of the general Japanese public during the war”. This was attributed in part to “apathy and what may be called ‘defensive indifference’…lending to a vague ‘they brought it all on themselves’ philosophy without considering its implications.”

Nevertheless, there was still compassion among some Australians. As part of a trip to Japan in 1947, artist and correspondent Albert Tucker visited Hiroshima. The picture he painted there is haunting and confronts the ethical and moral issues of the bomb. Tucker never felt he could fully encompass the suffering he saw there, stating in a later interview that he looks back on his work in Hiroshima “with tremendous regret … that I just simply didn't know more at the time.”

Depicts a small child standing in a burnt and destroyed landscape. A burnt tree fills the centre of the piece, with branches in the shape of swastikas. This work turns away from a focus on the barren landscape and towards Japanese suffering.

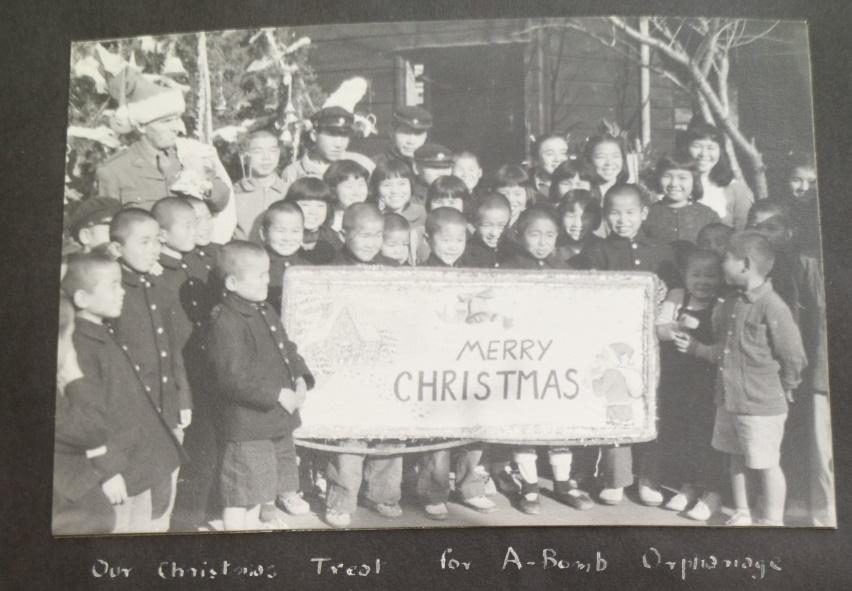

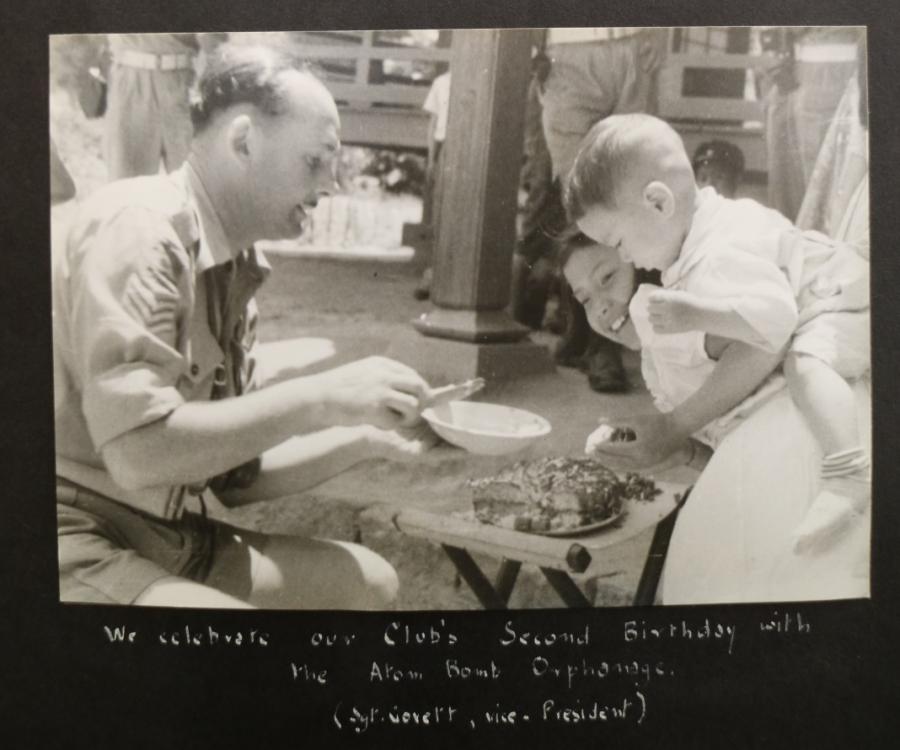

Major Jack Lee Bloomfield, an officer in the audit section at BCOF HQ in Kure, worked closely with the Hiroshima orphanage during his time in Japan. As president of the BCOF Tourist Club, Bloomfield helped fund donations of new books and toys and visited the orphanage regularly. In 1949 the president of the orphanage, Gishiu Yamashita, wrote to him: “It is indeed beyond any expression how I appreciate your acts of sympathy and feel very grateful to you.” Bloomfield demonstrated a capacity for compassion and inspired others to follow his lead.

A Christmas celebration held by the BCOF Tourist Club at the orphanage, with Bloomfield on the left dressed as Santa.

These connections to Australian service in Hiroshima help remind us that the road to peace and understanding is not an easy one. Australians struggled with the moral dilemma Hiroshima presented. What is the price of peace? And was it worth it?

The club’s vice-president, Sergeant Clement N. Govett, celebrating the club’s second anniversary with children from the orphanage. (PR01939)

Shortly after the Japanese surrender on 15 August 1945, Australian prisoner of war Kenneth Harrison decided to celebrate his freedom with his fellow inmates by travelling to Hiroshima. Originally captured in Malaya 1942, Harrison was a survivor of the Burma–Thailand Railway. He was later transported to Japan, where he worked at a shipyard in Nagasaki and then a coal mine in northern Kyushu. Despite his experiences under the Japanese, Harrison could not help but be affected by the devastation that he saw at Hiroshima. At the end of his visit he reflected:

“Now, as we left Hiroshima, our hatred of the Japanese was swept away by the enormity of what we had seen. All bitterness was shed and left behind forever in the silence, the desolation, the ashes of Hiroshima.”

Sources

Hiroshima: The Origins of Global Memory Culture (2014), Ran Zwigenberg, p.37-38

Albert Tucker full interview transcript from the Australian Biography Project, recorded 14th February 1994

https://www.australianbiography.gov.au/subjects/tucker/interview3.html

HQ BCB, BCOF Monthly Intelligence Summary, no.11 for the month of February 1947 (AWM114, 423/10/17)

Private records relating to the service of SX32964 Jack L. Bloomfield's involvement with an orphanage in Hiroshima Japan whilst he was serving at the BCOF HQ.

Road to Hiroshima (1983), Kenneth Harrison, p.267

The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1946), The United States Strategic Bombing Survey, p.15