The real life story behind Redgum's 'I was only 19'

John Schumann donated his guitar to the Australian War Memorial.

I was only 19 is the song that changed John Schumann’s life. But when the singer-songwriter sat down to write about the Vietnam War more than 35 years ago, he never dreamt the song he wrote would become a number one hit, or that its lyrics would one day be inscribed on a national memorial.

“As a young songwriter you are totally convinced each new song you write is going to be the next Stairway to Heaven,” he said with a laugh, “but it’s true to say that I didn’t think for a moment that this song was going to be as influential and as life-changing for me and others as it has been.

“It’s also a song that you can’t perform lightly. It means so much to other people … you have to concentrate and play it with sincerity and intensity every time you play it …

“You have to perform it like it’s the first time you’ve performed it, and you have to perform it like you mean it because the song demands it … [but] in lots of ways it doesn’t belong to me, it belongs to the people about whom it’s written.”

Schumann originally wanted to write a song about Vietnam veterans because he knew he could have been one of them. As a teenager in South Australia in the late 1960s, Schumann was the right age to be “swept up in conscription”, but his number never came up.

“It really was a case of, there but for the grace of God go I,” he said. “I was the right age to have had Vietnam on my personal horizon … [and] the army held no terrors for me … Like most families there was a history of service. My grandfather was a marksman on a merchant navy minesweeper during the First World War – he used to stand on a deck with a .303 and detonate mines – and then Dad was in the RAAF in the Second World War.”

Schumann’s father wasn’t too worried about the idea of him being conscripted – “He thought it would do me the world of good” – but his mother was far from comfortable with the idea of her boy going to Vietnam. “I didn’t understand why every time I had an asthma attack I had to go to the doctor, but she told me a bit later on that she was laying a paper trail in case my marble came up.”

It wasn’t until he was studying philosophy at Flinders University that Schumann started to learn more about the war in Vietnam.

“By the time I got to university, the war was in its final hours,” he said. “I had been in blissful naive ignorance about the war – other than what it might or might not mean for me personally – but once the light was turned on, I became opposed to our participation.

“It was a war of American imperialism, and we had no business there, and I was very keen to see the Australians brought home, particularly those blokes I knew over there.”

Schumann never forgot those who served and how close he came to being one of them.

“I had some friends who went and they came back fundamentally altered,” he said. “And that I think helped give rise to the song because I looked at these guys and again thought, there but for the grace of God go I... The songwriter in me could well imagine myself being sick and psychologically injured and being home from a war that nobody wanted to honour my service in. There was a sense of injustice, and … injustice will always fire me to get off the couch.”

He decided to write a song for the veterans, but he didn’t want to base it on media reports and his imagination. When Cold Chisel recorded Don Walker’s Khe Sanh, he thought he’d missed his chance, but then he wrote I was only 19, based on the experiences of his brother-in-law, Mick Storen, who had served with 6 Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR), in Vietnam in 1969.

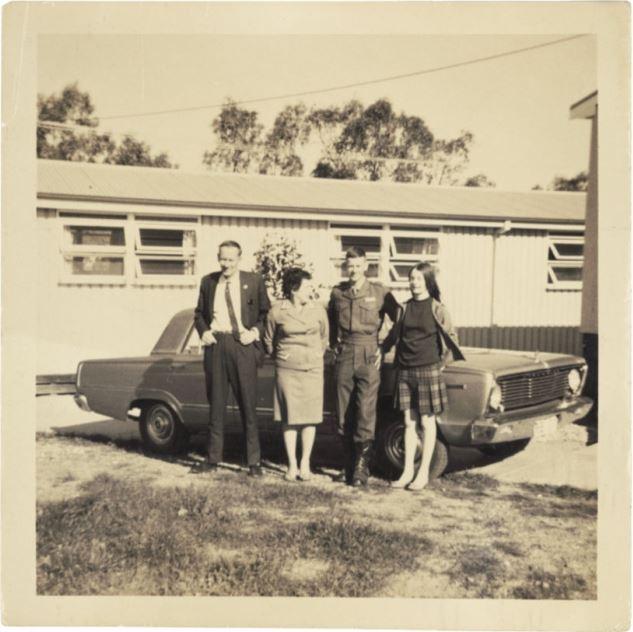

Mick Storen with his sister Denny and his mum and dad. Photo: Courtesy the Storen family

“I was going out with Denny at the time, and I knew her brother had been in Vietnam, but she told me that he didn’t talk about it,” Schumann said. “She brought him along to hear the band play at the Oxford Theatre in Unley [shortly before Christmas in 1981], and we all went out for a drink and something to eat after the show … Notwithstanding the fact that I’d been warned that he didn’t talk about it, I asked him – very possibly on the wings of a six pack – if he would be prepared to talk to me.”

Much to Schumann’s surprise, Storen said yes. But there were two conditions, the first being that Schumann didn’t denigrate Storen’s mates. “That was not what I wanted to do, so that was easy,” Schumann said. “And the other condition was that he heard the song first, and if he didn’t like it, then the song was not to see the light of day.”

Schumann agreed, and the pair met a few months later at Denny’s house in the Adelaide Hills. Storen brought with him a carton of beer and a small cardboard box containing his Vietnam memorabilia – photographs, slides, a couple of badges, a map and a few bits and pieces.

“He came up one night, and we had a long conversation, which I taped on cassettes, and I just listened to those cassettes over and over and over,” Schumann said.

When he sat down to write a few months later, the words just tumbled out. “It was like it’d already been written,” Schumann said.

“We’d done a gig … in Gippsland the night before, and I was living in Melbourne at the time with my friend David Sier. He had a little terrace house in North Carlton, and I went into the backyard. It had a little cottage garden and it had a little bench, and I sat in the sunshine with my guitar, and, really, it didn’t take very long at all to write the song. It was really quite extraordinary… As proud as I am of 19, that morning I felt as if I was little more than a conduit.”

He admits it was “pretty scary” playing the song to Storen for the first time. “He’s not very demonstrative at the best of times, but he did greet the song with silence, and not unreasonably, I thought that I’d really put my foot in it,” Schumann said. “I thought he was thinking, ‘How dare he? This guy’s a complete idiot and he’s going to marry my sister.’ But no, he liked it, and I was so apprehensive about the whole thing, I just remember he said, ‘Mate, you’d better go see Frankie.’ And he said that a few times.”

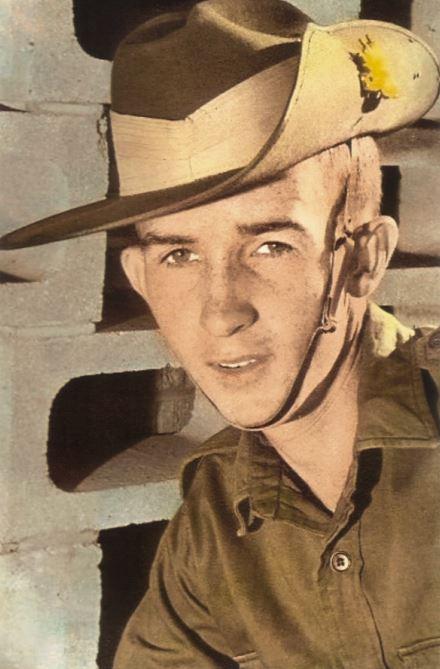

Frank Hunt during training in 1967. Photo courtesy Frank Hunt

In the original lyrics, Schumann wrote that Tommy “kicked a mine the day that mankind kicked the moon”, but Storen didn’t know any Tommys and wanted the name changed. It was Storen’s platoon commander, Lieutenant Peter Hines, who stepped on the mine in July 1969, but Storen didn’t want his name used out of respect for his family. He told Schumann, “You can use Frankie, but you’d better go and see Frankie to ask him if it’s okay.”

Frankie was Frank Hunt. He had been badly wounded in the same incident that killed Hines, and in January 1983, Schumann went to visit Hunt at his home in Bega. “I knocked on the door, and I don’t think he was very impressed,” Schumann said. “I was this long-haired, bearded, left-wing firebrand … but because I was a friend of Mick Storen’s, he let me in the house, and I played him the song, and he was knocked sideways too. He just wanted to hear it again and again.”

Frankie agreed to share his story, and when the song was released in March 1983, the impact was immediate. “Everybody I played it to was knocked out by it,” Schumann said.

The song went to number one, and four years later 25,000 Vietnam veterans marched through the streets of Sydney in a belated welcome home parade. For the hundreds of thousands of Australians who bought the record, Schumann suspects it was a way of saying sorry.

“I think I was only 19 provides an ‘I get it’ moment,” Schumann said. “Australians are fundamentally fair and decent, and I think I was only 19 was a story … that made us stop and think, ‘Oh, shit, we didn’t do the right thing by those blokes.’ It gave us all a chance to look over the fence, and look into the backyards of the Vietnam veterans who lived next door or down the street.

“I think we’ve learned to separate our position on the war and our position on the men and women who are sent to fight it. And I think that’s a very important distinction.”

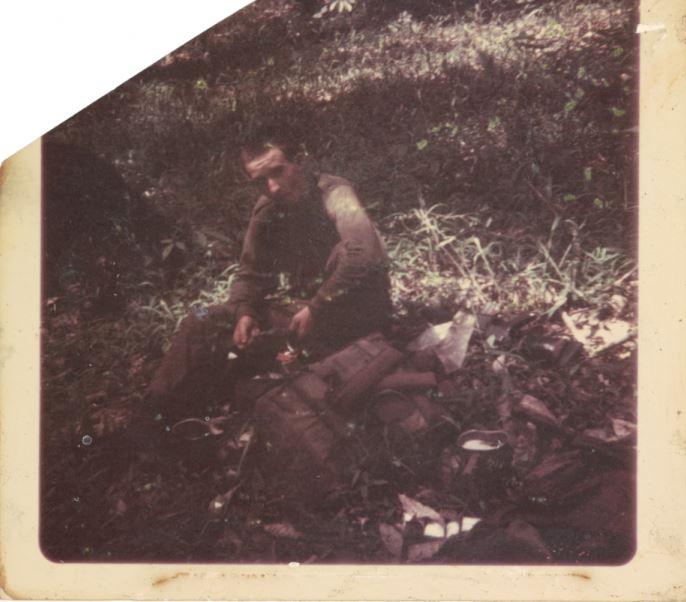

Frank Hunt in Vietnam in 1969. Photo: Courtesy the Storen family

More than 35 years later, veterans still approach Schumann to thank him for telling their story and helping their families understand.

“It’s the song that changed my life,” Schumann said. “On the basis of 19 … I’ve been places and met people and done things that I would never have hoped to have done in my wildest dreams. [But] it’s no credit to me. The work and the power of the song is, in lots of ways, nothing much to do with me … it’s the Australian people who have opened their hearts, and their minds, and elevated the song, and drawn it into the pantheon of Australian literature and culture.

“Sometimes I think that I channelled some other force that day … It’s almost as if the universe said, ‘Look … it’s really not fair about these Vietnam veterans. We really need to get everybody to understand what’s going on here, and how do we do that? Oh we’ll do it with a song.’ And they sort of peer through the clouds, and say: ‘See that guy with the left-handed guitar and the stammer, let’s pick him.’”

In June, Schumann will perform a new arrangement of I was only 19 with musical artist Bill Risby as part of the Vietnam Requiem concert in Canberra to mark the 50th anniversary of the Australian withdrawal from the conflict.

“I’m delighted and honoured beyond measure that I was only 19 was chosen to be a part of this requiem,” he said. “It’s very exciting and I’m deeply honoured.

“I think music can be a tremendously powerful and tremendously healing force and the more musicians, the greater the healing, the greater the power …

“19 is an anthem … [and] I think the fundamental power of the song is that it’s true.

“It’s tremendously important to veterans and you have to respect the song and respect them…

“They got together and then they started to swap their stories and share their experiences and they realised they weren’t on their own … so if I have done one thing in my life … that I’m really proud of, and really grateful that I was chosen to deliver to Australia, it’s I was only 19 because it helped bring them home and it helped us understand that you’ve got to honour and respect the men and women our government send to fight a war even if you bitterly oppose the war.

“I think the story in its simplicity and its detail and its compassion helped us understand and helped us not to blame the soldiers and the men and women of the army, navy and air force that we sent over to Vietnam.

“I am happy and proud to think that I was only 19 played a small part in that reconciliation…

“As a songwriter, you never think you’re going to write another I was only 19, because you know that’s not going to happen – a songwriter gets to write a song like I was only 19 once in his or her lifetime. That’s a real gift, and 19 has been a gift.”

John Schumann performs I was only 19 in the Hall of Memory.

The Vietnam Requiem concert is on at the Llewellyn Hall, ANU School of Music, Canberra, on Saturday 5 June 2021 and Sunday 6 June 2021. For more information, visit here.

I was only 19 is also the subject of an online exhibition at the Australian War Memorial. Named after the alternative title for the song, A walk in the light green, uses a range of items from the Memorial’s collection – including items loaned by families involved with the song and a series of interviews – to tell the story behind the song.