Identifying the Lost Diggers

Group portrait of eight unidentified members of the 2nd Division. Several of the soldiers wear identity bracelets in the shape of Australia.

They smile happily for the camera, laughing and posing with their friends. But for many, the photographs taken at Vignacourt in northern France would be their last before being killed on the battlefields of the Western Front.

For nearly a century, their images lay undisturbed in the attic of a French farmhouse until almost 4,000 glass-plate negatives were rediscovered in 2011, shedding new light on their final days and sparking a search for their identities.

Always behind the front lines, the small French village of Vignacourt near Amiens was a staging point, casualty clearing station and recreation area for allied troops for much of the First World War.

Portrait of Sergeant James Leonard Paddock MSM, Australian Corps of Signals, and Corporal Herbert Reginald Bain MSM, 1st Divisional Signal Company. Both men returned home to Australia in April 1919. The sidecar was made, by the men, out of parts from a damaged aeroplane, with the word 'signals' painted on the side.

It was there that a local French couple, Louis and Antoinette Thuillier, photographed thousands of troops as they passed through on their way to and from the Somme battlefields.

Louis knew all too well about the horrors of war. He had enlisted in 1914 at the age of 28 and served as a despatch rider with the French army until he was wounded.

When he returned home in 1916 to the farm and bicycle repair shop that he ran with his wife, he placed a sign saying ‘photos’ above their front door.

For the war-weary soldiers, it was a welcome distraction from the horrors of the Western Front, and they soon flocked to the Thuillier home to have their photographs taken. Antoinette was even said to have blown kisses at them to encourage them smile.

Portrait of two members of the 1st ANZAC Corps Cyclist Battalion. Identified on the right is Private Carl James Dettmann. A blacksmith from Kyneton in Victoria, Dettmann embarked with the 4th Light Horse Regiment in 1915, and was transferred to the 1st ANZAC Corps Cyclist Battalion in France in May 1916. He returned to Australia in October 1918.

Today, the collection is considered one of the most precious visual records reflecting the service and sacrifice of Australian soldiers in the First World War.

How it came to light nearly a century after the war ended is a tribute to the detective work of journalists Max Uechtritz and Ross Coulthart, and historians at the Australian War Memorial, who pieced together information from photographs that were appearing throughout France. They then tracked down one of the Thuilliers’ descendants, Madame Henriette Crognier, who was still living in Vignacourt and knew where the collection was stored.

She insisted the collection be taken to Australia for restoration, “pour les Australiens” [for the Australians!], and in 2012 more than 800 of the negatives were donated to the Memorial by its chairman, Kerry Stokes.

Portrait of two unidentified bandsmen with euphoniums from the Thuillier collection of glass plate negatives.

The men soon became known as the “Lost Diggers of Vignacourt” and featured in a touring exhibition which captured the public imagination. The exhibition closed for the final time on Remembrance Day, but the work to identify the men continues.

It’s a job the Memorial’s Photo, Film and Sound team is passionate about.

“Identifying the men can often be a slow and challenging process,” curator Joanne Smedley said.

“Once you put people in a uniform, and you put a hat on, and you turn your face in different angles, your face can look remarkably different.”

Facial recognition software is not always 100 per cent accurate, and when dealing with historical photographs that have wear and tear, fading and other marks, the ability to get an accurate result is even further reduced.

“We don’t have computer software that we can run through our collection so we approach it quite forensically where we can,” Smedley said.

“We use comparative photographs and look at where the ears are, how they attach to the face and where they actually sit on the side of the face – because there’s a remarkable variety to how they sit on the face.

“You don’t ever think of these things, but in photographs it can be quite obvious.

Portrait of Lance Corporal Robert Sumner, 6th Battalion, Australian Field Ambulance with Robert Thuillier, the photographer's son, dressed in a field ambulance costume.

“We also look at the cartilage, because everyone’s cartilage is different.

“We also look at the eye colour because that can look different in photographs. Somebody with blue eyes often has a very different look to somebody with dark brown eyes because there is a tonal difference that is quite obvious, even in a black and white photograph.

“We also examine their eyebrows, their hairline, the shape of their nose, and any dents and dings in the face, like a cleft in the chin.

“Of course, once you put a chin strap from a hat on, that can also affect things, so we try to be as scientific about it as possible.

“We have to be as careful as we can because we don’t want to put the wrong name with a photograph because that would be worse than having no name at all.

“We have to become quite detective-like in how we pull information together, but it’s not just the visual information that we use. We are also looking at war diaries and service records to see if everything adds add up. If somebody has been identified as being in one of the images, but we find that they were in hospital at the time, that would make it nigh on impossible for them to have been at Vignacourt.”

Portrait of an unidentified 2nd Division Signaller with a despatch motorcycle.

Curators also carefully examine the uniforms and study the colour patches, unit stripes and rank badges.

“We don’t really know the mechanics of what was happening at the time, so it does make it potentially quite tricky,” she said. “Sometimes the soldiers are pictured in uniforms without any of the things that we know they should have had, simply because they may not have had time to sew them on. And sometimes the shape of the colour patch doesn’t match what we know it should have been, yet we have the actual photograph, so they may have just grabbed someone else’s uniform.”

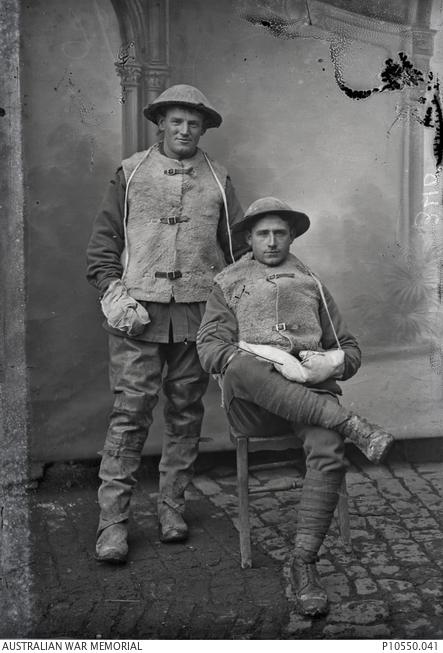

A portrait of two men of the 1st Australian Division, 1916.

Today, more than 160 of the men in the images have been identified, but the work to identify them continues. The high-resolution photos were taken on glass, printed with an oil-and-water technique on to postcards, and then posted home, enabling soldiers to maintain a fragile link with their loved ones back in Australia.

They show many different aspects of the Western Front, from military life to friendships between soldiers and local residents, and are often informal and relaxed, showing men trying to enjoy themselves away from the horrors of the front line.

“The lovely thing about a portrait is that you’ve captured somebody’s image at a moment in time,” Smedley said. “The Vignacourt images are a really interesting counterpoint to the images that were taken at home when the men were still in training: they were in camp, they hadn’t seen the Western Front, and they hadn’t been to Gallipoli. Everything was new and exciting. It’s an adventure, and they don’t really know what they are going into. And then you look at them in comparison to the Vignacourt images, and you look into the soldiers’ eyes. They are really quite powerful: they really capture the weariness, the mateship, the cold, the mud, and certainly none of the things that they have experienced back home.”

Portrait of an unidentified French and Australian soldier. The Australian soldier wears a sheepskin vest and mittens to ward off the cold in what was one of the coldest winters in decades on the Somme.

The photos were taken between late 1916 and late 1918, some scenes capturing the last day of the war, 11 November 1918.

“You don’t have to know what happened to sense some of what they are experiencing, but of course once you do know the story, you can’t ‘un-know’ it. I think that’s the real power of a studio and a photographer trying to capture and portray people during the war,” Smedley said.

“You try to make sense of someone’s story through images, objects and artefacts that help to add little bits of detail, but the fact that the Vignacourt negatives have survived at all is really interesting. Having an actual photograph that was taken on the Western Front has really captured people’s imagination.

“The Vignacourt images are a bit of a mystery because there are so many unidentified people, but they give you a bit of an insight into a time that we hear a lot about, but that we can’t really imagine.”

If you think you have identified a relative in one of the photographs in the Thuillier collection, please visit the Photograph caption amendment suggestion page.

The Memorial's Thuillier collection can be viewed online.

Ross Coulthart’s book The Lost Diggers is available from the Memorial shop and online.

Group portrait of four members of the 13th Australian Light Trench Mortar Battery. The two soldiers in the front row hold bottles of French wine. Identified in this photograph are Corporal Robert Chaffey Stuart, third from left, and Private John Charles Bitton, fourth from left. The soldiers in this photograph each posed for their own individual portraits. In these portraits they are each wearing the same helmet, suggesting it was a prop owned by the photographers.