'Peace and quiet is what one asks for'

Sentries at prisoners' tent, pastel, gouache on grey laid paper mounted on buff paper, 1915.

It’s Spring 1915 and a lone soldier stands on guard outside a prisoners’ tent, armed with his rifle.

The guards’ tent is brilliantly lit by hurricane lamps and the warm red glow of the gas stoves the men use to boil their billies.

The surrounding prisoners’ tents have been plunged into darkness after an early lights out.

It’s a moment in time that was captured more than 100 years ago in a deceptively simple, but elegant, pastel and gouache drawing titled Sentries at prisoners' tent by the Australian artist Iso Rae.

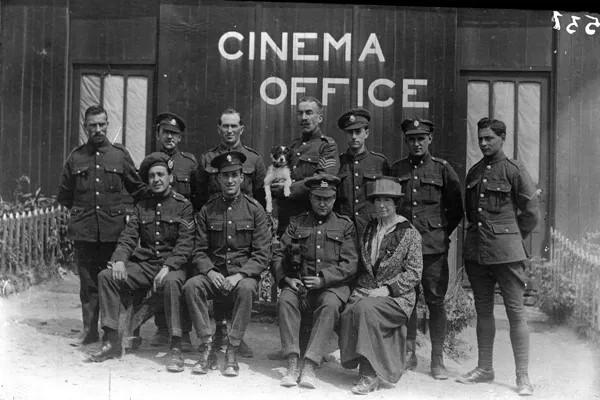

Iso Rae photographed with British soldiers outside the Cinema Office. This is the building depicted by Rae in her work Cinema queue. Photo: ©Quentovic Museum-City of Étaples-sur-Mer. Caron Collection.

One of only two Australian women artists who were able to depict the First World War from such close quarters, Rae was never an official war artist. But she produced more than 200 pastel drawings while working for the British Red Cross’s Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) in the large army camp at her adopted home of Étaples.

Between 1915 and 1919, Rae documented conditions in the camp, making observational drawings of hospitals, barracks, recreation huts and tents, soldiers drilling, horses, German prisoners of war, and even a football game, in her gentle, understated style.

Her drawings reflect a woman's perspective of the war, not of direct front-line action, but of everyday events behind the lines: preparing for battle, caring for the wounded, keeping the prisoners occupied, and entertaining the troops with football games, cinema films and live theatre.

More than a century later, Rae’s works are an important part of the art collection at the Australian War Memorial.

Étaples, pastel on paper, 1917. A French soldier with his mount at the camp at Étaples.

For art curator Alex Torrens, they are particularly significant, providing a rare view of the war through a feminine lens.

“The fact that these wonderful drawings exist at all is remarkable,” Torrens said.

“Australian women were excluded from the creation of a national visual record of the war.

“There were of course the restrictions of gender and geography at the time, and then no Australian official war artists were women.

“This was largely due to a conviction that artists needed to have experience of the battlefield to create authentic images of the Australian experience of war.

“Yet Iso Rae, an accomplished and prolific artist, was as close as any Australian woman could be, living and working amidst the largest allied military camp in France, stoically continuing to create her art.”

German prisoners working, pastel, pencil on buff laid paper, April 1917. German prisoners of war repairing pavement on a railway platform. ‘Anzac Camp’ is in the background.

Isobel Rae was born in Melbourne, in August 1860 and studied at the National Gallery School in Melbourne with the Irish-born Australian painter and art teacher, George Folingsby. Her fellow students included the likes of Tom Roberts, Frederick McCubbin and John Longstaff.

She travelled to France with her mother and sister in 1887, and settled in Paris, before moving to the artists’ colony of Étaples three years later.

At Étaples, Rae worked alongside Australian artists such as Hilda Rix Nicholas and Rupert Bunny, and exhibited at the Paris Salon. Her paintings were Impressionist in style, often large in scale and painted outdoors – en plein air – depicting the landscapes and people of Étaples.

When war broke out in 1914, most of the artists left, but Rae and her sister Alison refused to leave. Their mother was unwell and they were reluctant to move her.

Troops arriving at Anzac Camp, pastel with carbon pencil on thick grey flecked paper, June 1916. Australian troops marching into ‘Anzac Camp’ at the Étaples army camp.

Alison shared her fears and hopes in a letter to a friend in Australia shortly after.

“I have not had the heart to write,” Alison wrote.

“We are in the midst of a very terrible war, and I cannot tell you how many thousands of English [British] soldiers have passed through here during the last fortnight on their way to the seat of war.

“We live quite near the station and from the upper windows see many of the trains pass. Often we go to the station with postcards, flowers, cigarettes, or anything they like to have.

“They are all in khaki and look splendid.

“Some jump out on the platform to shake hands and talk for a few minutes before being borne swiftly away again – perhaps forever...

“Ten thousand passed in one day last week. Another day 15 thousand...

“We have seen enormous numbers of guns, cannons, ammunition pass slowly through...

“I cannot write of all the things we have been through since.

“We are, I believe, the only English in town now...

“Many people went. But we do not want to break up our home unless absolutely obliged to do so.”

23rd General Hospital, pastel with gouache on grey laid paper, November 1915.

Strategically situated in northern France, along the River Canche, the small fishing port of Étaples became the largest British army base of the war, serving British, Canadian, Scottish and Australian forces.

It was used as a training and retraining ground for forces about to enter battle, but also as a depot for supplies, and a detention centre for prisoners, both allied and enemy, and was the site of several large hospitals, which were set up to treat the wounded from the Somme battlefields on the Western Front.

Australian troops were stationed at Étaples until June 1917, but wounded Australians were sent to the hospitals there throughout the war.

By 1917, more than 100,000 troops were camped among the sand dunes, and the hospitals were able to deal with 22,000 wounded and sick at any one time.

More than 100 trains passed through on the railway there each day, carrying troops and supplies to the war.

Iso Rae recorded it all in her drawings.

Rue de la Gare (Station Street), pastel, gouache, pen and black ink, pencil on grey card, January 1918.

“Iso Rae’s drawings were essentially private records unshaped by political or official agenda,” Torrens said.

“They allow us to see wartime Étaples through her eyes.

“There’s one that is of Rue de la Gare, or Station Street. It’s the view looking down from the flat where she lived with her sister. The composition of the work shows the pervasiveness of the military presence, drawing our eye along the busy thoroughfare towards the sprawling tent city which fills the horizon.

“Others reveal the grim reality of the camp, the harsh winter conditions, the plight of prisoners of war, the fleeting nature of relationships, theatrical entertainment for men who were ‘NYD’ (not yet diagnosed) or shell shocked, the British labour camp, and members of the military police.”

Infantry returning from training ground (Bull Ring), pastel with gouache on grey laid paper, November 1917.

In September 1917, there was a series of mutinies in the camp as soldiers protested against the harsh treatment and conditions.

The mutinies were largely censored at the time, but Iso Rae documented them in her work.

Her drawing Troops in Town after Riots Previous Sunday, September 1917, shows the town square teeming with military police as troops who had been confined to their quarters on the other side of the river were allowed into the town.

“Her work is proof that the mutinies actually happened,” Torrens said.

“In addition to their documentary value today, Rae’s drawings are a unique artistic depiction of the war.

“Artistically, she was exploring the compositional opportunities presented in the shapes and repetitive patterns of tents, men marching or horses tethered, or the aesthetic possibilities in contrasts of light and dark.

“Working for much needed income, sanity, or both, Rae the artist was making the best of a career interrupted, in conditions that were far from ideal for art-making.

“You can see some of the paper she used is quite rudimentary. It’s still artist’s paper, but she went from someone who was painting post-Impressionist style paintings [outdoors] on canvas to using paper and pastel and whatever she had available to document what was happening around her.

“The paint and canvas were either something she couldn’t afford, or something that was simply not available to her at that time, so she was doing what she could, using paper, pastels and pencil in a much smaller style.

“She was trying to make the best art in conditions that weren’t very conducive to it.

“It would have been quite brutal and scary at times.

“They were actually there when Étaples was bombed...

“The Germans shelled it in 1918, and their house was destroyed, along with all their possessions.

“Alison’s foot was quite badly wounded in the shelling, and a couple of the hospitals were bombed, killing some of the nurses and doctors, and the soldiers as well.

“Iso had all this going on in the background, while she was just trying to live, and survive through this awful war.

“But she continued to make art.”

YMCA Walton hut, pastel, pen and black ink, pencil on buff laid paper, June 1917.

At the end of the war, Rae and her sister moved to the nearby town of Trepied to recover. Their mother had died during the war in 1916.

But even though the war was finally over, it was never far away.

Rae and her sister eventually returned to Étaples, where they were regular visitors at the nearby British Military Cemetery.

In 1929, Rae wrote to her friends in Australia: “I found the grave I wanted, and the head-gardener snipped me off a tiny rose bud to send to the mother of the boy buried there. It is now on its way to Melbourne.”

Alarmed by Hitler’s rise to power in Germany, Rae and her sister moved to England in 1934 and settled at St Leonards-on-Sea in Sussex.

Alison shared their fears and concerns about the coming of the next war in letters to her friends in Australia: “Over in our dear France there must be great distress and anxiety concerning the future. Peace and quiet is what one asks for.”

As the new war began, Iso Rae’s mental health deteriorated. She was admitted to the Brighton Mental Hospital in November 1939 and died four months later at the age of 79.

Today, the Australian War Memorial holds 18 of her drawings in its collection.

“Her works are incredibly rare,” Torrens said.

“And she hasn’t really received the recognition that she deserves, because she lived overseas and never returned to Australia.

“She did 200 drawings during the war, so it’s a substantial, sustained body of work.

“It really is an incredible private record of what life was like in Étaples during the war, but her wartime works weren’t even that well known until they were discovered in the 1970s.

“Seventy-five of her pastel drawings were brought to Australia in the 1970s and the Memorial purchased nine of them at the time.

“They not only document what life was like behind the lines, but are also really significant for their quality.

“And although she was never an official war artist, they are just as authentic, showing the war through a feminine lens.

“We’re very lucky to have them.”

More than 100 years later, they remain a poignant reminder of the everyday lives of the men and women who served and died during the First World War.