'He loved it ... and he put his blood, sweat, and heart into it'

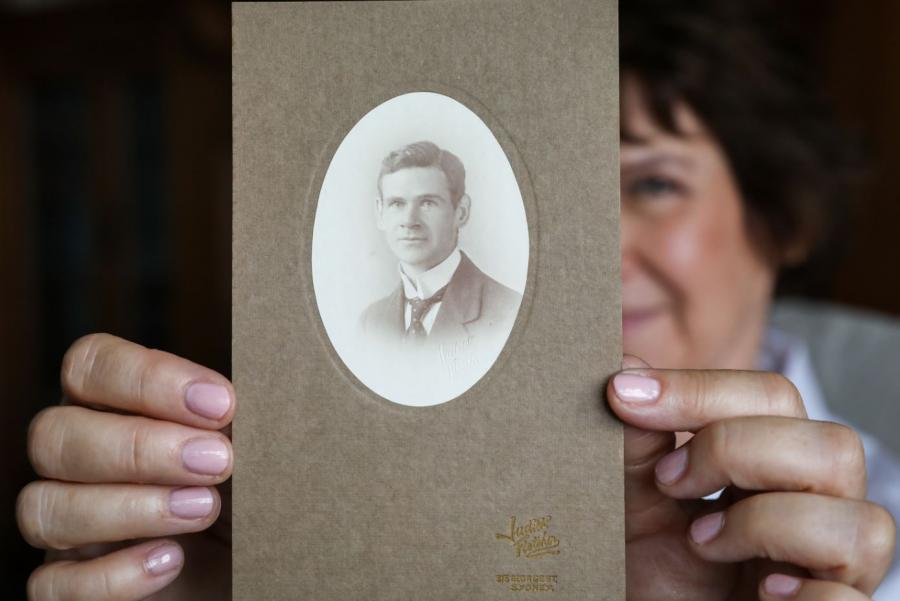

Lucy King with a portrait of her grandfather John Crust. Photographer: Katherine Griffiths

In the midst of the Second World War, Sydney architect John Crust climbed Mount Ainslie to paint a watercolour of the newly-built Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

It was not long before the official handover of the building that he had dedicated years of his life to; a building which would become one of the most iconic buildings in the country.

“That was him saying goodbye to the Memorial,” said his granddaughter Lucy King.

“He loved it, and he drew it several times; it was his baby, and he put his blood, sweat, and heart into it. I don’t think he left any stone unturned; he gave it everything.”

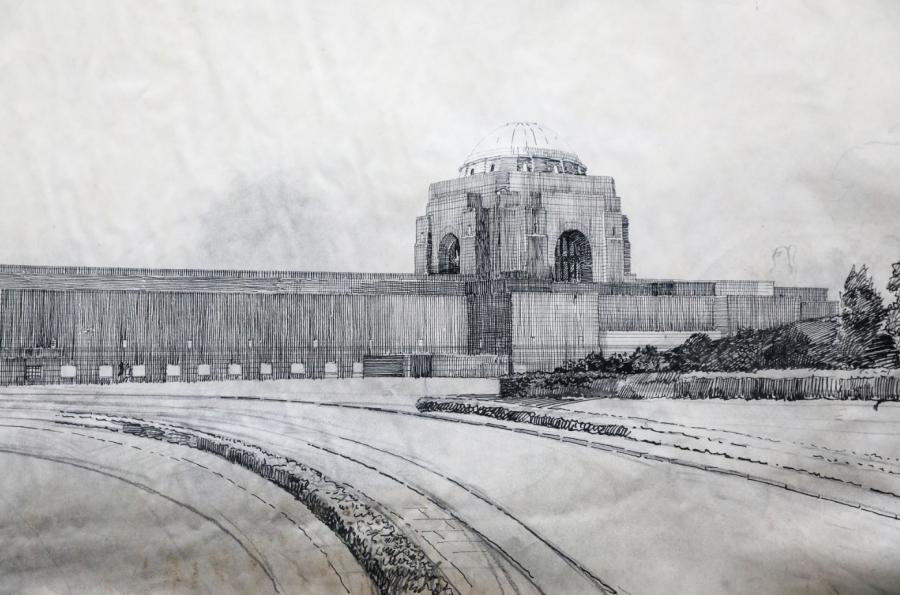

John Crust’s 1928 watercolour of the proposed Memorial, showing the planned Commemorative Area and gardens.

Her grandfather, John Crust, was one of the architects behind the Memorial. His younger brother William had been killed in France during the First World War and he knew all too well what the Memorial would mean to those whose loved ones never made it home.

Lucy discovered the watercolour more than 70 years after it had been created, among her grandfather’s personal papers at the family home that he designed and built in the Sydney suburb of Mosman during the First World War.

“It was like a treasure trove,” Lucy said. “He picked the things that he thought he could do well with heart.”

Lucy discovered a remarkable collection of Crust's work that includes architectural plans and drawings of the Memorial as well as sketchbooks, paintings, letters and diaries. Photographer: Katherine Griffiths

The vast collection includes everything from plans and blueprints for the Memorial’s iconic dome and facade to designs for the doors to the Hall of Memory and the chain on the parapet above the main entrance.

“He just drew and drew and drew,” Lucy said. “He was always playing with the design – different entrances, different facades … and was busy experimenting using reams of paper trying to resolve the issues, and so he would look at it, and look at it, and change a bit here, and change a bit there, until he was happy with the balance.”

A quiet and unassuming man, John Crust was born in Leeds, England, on Christmas Day 1884.

He showed a talent for drawing from a young age and left school at the age of 13 to work for the architect and surveyor, Thomas Edward Marshall in Harrogate, Yorkshire.

He soon gained a reputation for his “excellent all round knowledge” and was praised as “a good and expeditious draughtsman, [who] has considerable knowledge of design, and is an expert perspective artist in colour”.

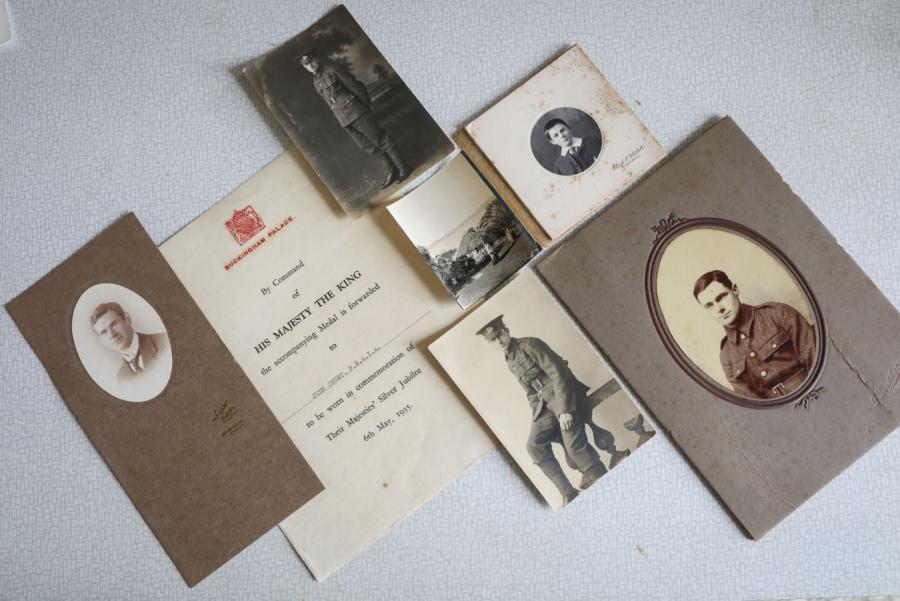

A collection of family portraits of Crust and his brother William who was killed in the First World War. Photographer: Katherine Griffiths

In 1904, Crust was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Advised to give up architecture and live an outdoor life, he spent the next six months living with his aunt on a farm in the Yorkshire countryside, before migrating to Australia.

“That was his one way ticket to health, and a life,” Lucy said. “He wasn’t going to have health and a life in England pre-antibiotics – it wasn’t going to happen – so through the goodness of people, at the age of 19, he was able to get on a ship and sail for Sydney.

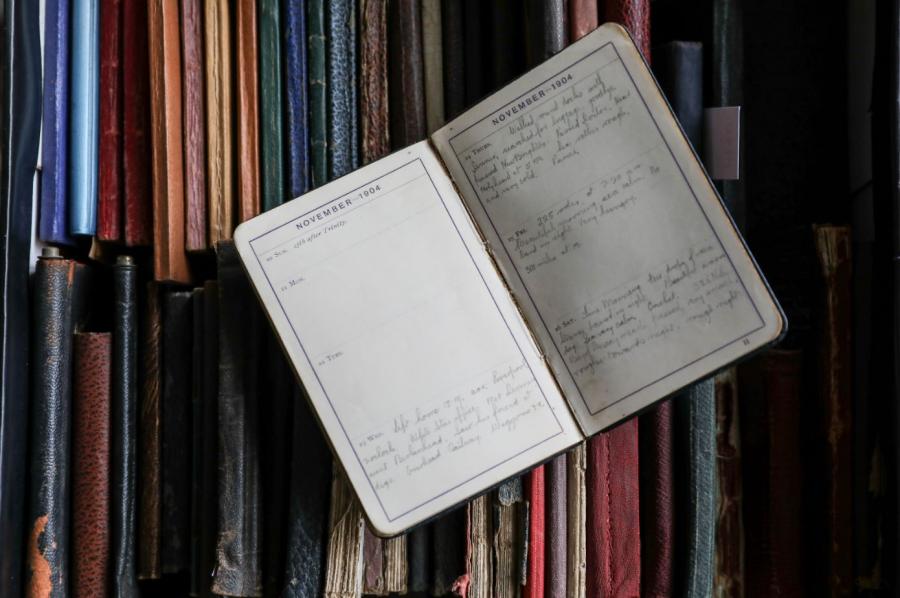

“His first diary starts off on the day he walks away from Harrogate and the family home, and at the back of the diary, there is a list of people with sums of money next to their names – one pound here, 10 pounds there – and I’m sure that’s the amounts that people gave to him or loaned to him so that he could come to Australia to regain his health.”

Crust kept a collection of diaries detailing his work. Photographer: Katherine Griffiths

Lucy King treasures her grandfather's collection of letters and diaries. Photographer: Katherine Griffiths

Crust celebrated his 20th birthday on board the ship and spent his first six months in Australia working on a farm near Temora in country New South Wales. In his diary, he meticulously records how he spent his days planting cabbages, harrowing fields, threshing grain, working the cart and dray, and cooking and peeling potatoes.

“I was not very happy there,” he later wrote in a letter to one of his benefactors. “But it built me up again which was what was required [and] by that time my health was quite restored.”

When he was offered a job as a draughtsman in Tasmania he “jumped at it”. He arrived in Launceston on 19 July 1905 and started work with the firm, J and T Gunn, that very afternoon.

“Working was his way forward, and how he could help his family in England,” Lucy said.

“He came from a poor family and he worked hard to improve himself and to support his mother and family at home in England. He sent as much money as he could back to his family in England right up until 1940 when the last of his siblings died.”

A quiet and unassuming man, Crust dedicated years of his life to the Memorial. Photographer: Katherine Griffiths

Crust went on to work in Sydney and Melbourne, gaining a reputation as a “quick and reliable draughtsman” with a talent for design and perspective. In Melbourne, he worked with the renowned architect John Smith Murdoch who became the chief architect of the Commonwealth of Australia and designed Old Parliament House in Canberra. Murdoch praised Crust’s work as being of an “exceptionally high quality” and wrote that Crust was “entrusted with the best class of work” which he “always carried out with great diligence and enthusiasm”.

When the First World War broke out, Crust tried to enlist but was rejected on medical grounds. His younger brother, Lance Corporal William Crust, served with the 1st/5th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment (Prince Wales’s Own), and was killed near Thiepval in France on 3 September 1916. Crust would not learn of his brother’s death until 31 October, one day after Crust had written a letter to him.

Crust's brother died during the darkest days of the First World War, just as the concept for the Memorial was conceived by Australia's official war correspondent Charles Bean. Photographer: Katherine Griffiths

“It must have been awful,” Lucy said. “He couldn’t go, and now he had lost his brother, so I think that when the idea for the Memorial came up, it meant a lot to him, it really did.

“It was a tribute to his brother, and to all the fallen, and to his country.”

Crust’s brother had died during the darkest days of the war, just as the concept for the Memorial was conceived by Australia’s official war correspondent Charles Bean.

Crust put his heart and soul into his plans for the Memorial. Photographer: Katherine Griffiths

Bean had seen first-hand the devastation of the First World War on Gallipoli and the Western Front and was determined that the men and their deeds should not be forgotten. He envisioned the Memorial as a shrine to their memory, a museum to house their relics, and an archive to preserve their thoughts and deeds.

When an international architectural competition to design the building was launched in 1925, Crust was determined to enter. Entries were to include plans for a Hall of Memory and a Roll of Honour listing the names of the more than 60,000 Australians who had died during the war.

“He worked nights and on weekends to get his entry in and he was the only one who came in on budget,” Lucy said.

“I think he looked at what Bean wanted and he took the money seriously … This was not about him saying how clever a designer he was, and how creative he was, or that he was the greatest architect ever, it was about designing a Memorial to honour the fallen, and I think he thought being over budget was a deal breaker.”

Crust knew all too well what the Memorial would mean to those whose loved ones never made it home. Photographer: Katherine Griffiths

By the time the competition closed in 1926, 69 entries had been submitted, all of which were rejected. Only Crust’s entry could be built within the approved sum of 250,000 pounds. He had proposed that the Roll of Honour be inscribed within cloisters around commemorative courtyards, rather than in the Hall of Memory. When no winner could be found, Crust and another entrant, flamboyant Sydney architect Emil Sodersteen, were asked to submit a joint design.

Their joint design was accepted in 1927, and there were hopes that the Memorial would be built by 1931. However, the Great Depression caused significant problems: adjustments were made as construction work stalled, and there was debate about whether it was better to commemorate servicemen who had given their lives or support those who were out of work.

As a compromise, work on the building was divided into two stages: the storage and exhibition spaces would be constructed first; and the Hall of Memory and cloisters would be completed later.

Construction of the Australian War Memorial viewed from the west. Canberra, ACT. 1940-08

Workmen surrounded by scaffolding and building equipment pause during the construction of the outer wall of the south facing arched window of the Hall of Memory.

Building finally commenced in February 1934, but conflict soon arose between the two architects, and Sodersteen resigned in 1938, leaving Crust to complete the building alone.

When the building was opened to the public on Armistice Day 1941, Crust travelled to Canberra for the opening with his wife, Irene, intending to stand quietly among the crowd that had gathered for the occasion. When the Memorial’s director, John Treloar, realised the oversight, he insisted Crust and his wife be seated on the dais with the other dignitaries. The man whose joint vision for the Memorial had now become a reality sat quietly at the back, out of the limelight.

John Crust and his wife Irene in the garden of the family home he designed and built in Mosman during the First World War.

Now, almost 80 years later, Lucy feels a special connection to her grandfather whenever she visits. She was only eight years old when her grandfather died in 1964, but has fond memories of him and the building he devoted so much of his life to.

“I love it and I’m extremely proud,” she said.

“Whenever I go to Canberra I look for it, I stretch for it, and I’m proud of it.

“I love the feel of it, and when I see the lanterns at the entrance, or the grills on the windows, or the chain on the parapet, it’s really special to me because I have the drawings that he drew when he designed them, and I think to myself, they’re still here.

“These are little things; most people wouldn’t see them, and wouldn’t know what I know, but I think, ‘It’s still here, John Crust, it’s still here.’

One of Crust's drawings of the Commemorative Area. Crust suggested placing the Roll of Honour within cloisters in his competition entry, solving the problem of meeting the Memorial competition specifications within budget. Photographer: Katherine Griffiths

“As he wrote afterwards, my grandfather devoted many years of his life to it, and I think you don’t take those words lightly.

“The Australian War Memorial was his gift to the country that had been very good to him. It was enough for him that the building was as good as it could be. Personal aggrandisement was not in his nature. He was just prepared to put one foot in front of the other and get the job done to the best of his ability.

“He loved it and he followed it until the day he died.”

In his own words

A collection of architectural plans and drawings documenting the design and construction of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra has been rediscovered at a family home in Sydney more than 70 years after it opened on Armistice Day 1941.

The vast collection of work belonged to Sydney architect John Crust,