'It never goes out of your mind'

It was July 1945. Ken Keamy, a sapper with the 2/5th Field Company, was prodding the sand with a thin pole, searching for mines and booby traps.

“I was bloody scared as hell,” he said. “Everyone was.”

The then 21-year-old had just landed at Balikpapan, the site of the last major Australian ground operation of the Second World War.

“We landed on the 1st of July,” he said.

“But you were only young, and you didn’t know what to expect.

Balikpapan, Borneo, 1 July 1945: Troops of the 7th Australian Division landing at Balikpapan.

Balikpapan, Borneo, 1 July 1945: Soldiers from a unit of the 7th Infantry Division carrying a wounded soldier on a stretcher along the beach. Smoke is billowing over the beach from oil tanks set on fire by the naval bombardment that pounded the Japanese defences.

“The coast had been mined by the Japanese, and they got engineers in, and they did underwater searches for explosives and things…

“But the worst part was when the ship came in. We had to drive into the water and up on to the land and on to the shore.

“The front part [of the ship] was open, and they had these big platforms off the front of them.

“As you were driving off, they were driving back with wounded people already, and you could see them with great gashes in their legs, and all that sort of stuff…

“It was a bit hard to take... You thought it was going to be you next.

“But the navy ships were out there pounding the place, day and night, for a long time, and they were marvellous.

Balikpapan, Borneo, 1 July 1945: Assault barges at the beach head at the time of the landing.

Balikpapan, Borneo, July 1945: Australian artillerymen in alligators, amphibious tracked vehicles, making for the beach during the landing at Balikpapan, Dutch Borneo. On shore, smoke from naval bombardment of enemy positions is rising.

Balikpapn, Borneo, 12 July 1945: Last dash to shore, aboard American manned Alligators, during the landing of Australian troops at Balikpapan, Borneo. Smoke from the ruins of enemy positions and burning oil wells is visible in the background. Shore installations were subjected to an intensive naval bombardment before the landing operation.

“We landed at eight o’clock, and a couple of Japanese Zeros tried to strafe us, but a few Spitfires got those, and shot them out of the air, so we managed to land alright…

“The Japanese had booby trapped a lot of the areas there … and it was pretty nerve-wracking …

“We had mine detectors, but they didn’t always pick them up … They were pretty primitive detectors in those days, and could easily miss them, depending on what depth they were, and how big they were.

“So you had a prodder most time, and you would go around prodding, trying to find them … but you just had to be so very careful.

“We lost 12 people in one explosion. The Japanese had 44 gallon drums of explosives buried in the ground, and we were going up the hill.

“It was a grassy hill, and they were delousing these mines, and making them safe, and as they progressed, one of them triggered one, and it blew 12 of our guys up.

“It was shocking, of course. And I rolled down the hill – most of us did – with the blast …

Balikpapan, Borneo, 1 July 1945: A sapper with a probe, left, and a sapper with a mine detector, right, members of the 2/11 Field Company, looking for mines while clearing a lateral beach road.

Balikpapan, Borneo, 1 July 1945: Troops of the 2/9 Field Company, Royal Australian Engineers, searching for mines soon after the landing at Balikpapan.

“When we got through there, we got into the old town, and there weren’t many people there. It had been pretty badly knocked about, and we had to make the mines safe and the booby traps and all that …

“But one of the worst things was that as the Japanese were retreating, they made the men kneel in the streets wherever they were and they tied their hands behind their backs and chopped their heads off …

“They took the women and kids with them, but they killed most of the men in the streets and that was the most shocking part.”

Codenamed Oboe Two, the landing at Balikpapan was the largest of the Oboe operations mounted by 1 Australian Corps around Borneo, and the largest ever amphibious assault involving Australian forces.

Ken, now 97, remembers it all as if it was yesterday.

Balikpapan, Borneo, July 1945: A section of coastline at Balikpapan, showing ruined palm trees and houses. The damage is the result of the naval bombardment before the Allied landing.

Balikpapan, Borneo, July 1945: Wrecked oil wells caused by the pre-invasion bombardment.

It was a world away from where he grew up in country Victoria, the son of the local school teacher.

The second eldest of six children, Kenneth Keamy was born in Yarram, south Gippsland, on 19 October 1923. He was boarding with an uncle in Melbourne and working in the city when he was called up in January 1942.

“I’d tried to join the air force at 17, but my mum wouldn’t let me,” he said.

“My older brother Cecil was with the signals mob in New Guinea and that… and I wanted to be a pilot, but she didn’t want me to go until I had to, and then as soon as I turned 18, the army grabbed me.

“I had to go to Surrey Hills Drill Hall on a Saturday morning and have a medical examination … If you got through that, you were told to report to the drill hall again in a fortnight’s time … From there, they sent us up to Seymour – they’d built a new camp for us in Nagambie Road – but we didn’t know where we were going … they just said bring a cut lunch with you …

Soldiers marching through Seymour township as they return to the nearby Puckapunyal Army Base.

“At night time there, you could hear people weeping, and in the morning, they would come out, and they were older men, older than you, weeping at these primitive conditions. And that was awful. I never slept that night … To go into the army and hear these men weeping through the night, you were left wondering what to expect.

“Things were pretty crook around that time, when Japan entered the war.

“They didn’t even have any uniforms for us. We were training in our suits – the business suits we’d gone up in – and they issued us with thick cardboard to put in our shoes as they wore out, until they got boots for us.

“We walked to Bonegilla near Albury … It was 138 miles, past paddocks with horses and things, just outside the towns … and it took us three days.

“The move was supposed to be all hush-hush, and no one was supposed to know we were moving up there, but as we went through Euroa, the farm houses were literally on the fence line, and these ladies were there with hot scones and jam, giving them to all the chaps who went through, so that was good.”

Elevated view of the jetty at Horn Island used by the 74th Anti-Aircraft Searchlight Battery.

After training, Ken went on to serve with the 5th Machine Gun Battalion, undertaking garrison duties in the Torres Strait.

“I was with a machine gun battalion on Thursday Island and we had the whole island protected with machine guns,” he said. “They thought the Japanese were going to attack it, but they found out later that there’s supposed to be a Japanese princess buried there, so the story was that although they used to bomb the islands around there, they wouldn’t bomb Thursday Island…”

He remembers seeing the American B-17 “Flying Fortresses” as they flew overhead and the Supermarine “Walrus” amphibian aircraft as they battled wild seas and rough weather.

“They tried to get these Flying Fortresses off the ground … and one landed in the sea, and another went in behind him,” he said.

“They were the biggest planes they had … and when another plane landed and crashed in to the sea, we broke into it, cut the door out, and got them out.”

Others though were not so lucky. More than 70 years on, Ken still thinks of a group of American airmen who died in the Torres Strait and are now buried in the cemetery on Thursday Island.

Ken transferred to the Australian Imperial Force in March 1943, but was struck down with dengue fever shortly afterwards.

“I went to get up out of bed one morning, and I fell on the floor,” he said.

“We had built stretchers with makeshift stuff out of the bush and a hessian pallet base, and I tried to get up again, and the same thing happened.

“I was put in the hospital at Thursday Island – a lovely old hospital there – and I was in there for some time before they sent me over to Prince of Wales Island.

“They had a little old fisherman’s hut there, and they used to send you there to recuperate.

“It was really bad. When you were standing up, you had to hang on to the tree branches, because you were so weak, and that was a shocker….

“They tried to get more food out to us there, but the little plane that was trying to drop it couldn’t land because of the wind and the rough seas.

“It was one of those ‘Walrus’ planes, with a propeller at the back, and even it couldn’t do it. It was more or less nearly flying back to its own airport because the winds were so shocking…

“It landed in the sea, and we got a radio message to fend for ourselves… so we walked across the island, and threw gelignite in to the water to catch fish.

“It was more or less look after yourself by that stage, so we caught these fish, wrapped them in grass and that, and cooked them in the fire..”

A Supermarine Walrus amphibian aircraft being pushed and towed ashore for repairs.

A Vickers Supermarine Amphibian Flying Boat Seagull aircraft, also known as a Walrus.

When he recovered, Ken left Thursday Island with 100 other men, bound for Red Island Point, Cape York in August 1943. Their job was to lay more than four miles of pipeline from the Jardine River to the supply tanks at Mutee Head, and then a pipeline along the sea bed so that ships could fill up with water for transport to the Torres Strait Islands in the dry season. They had already helped build a new jetty at Thursday Island to allow bigger ships to dock while they were there.

The following year, Ken was sent to Kapooka to complete the engineers training course at the Royal Australian Engineers Training Centre. Recruits learnt everything from squad and rifle drill, marching and physical training, and bayonet practice and complete small arms training, before completing demolition work, mine laying and detection, followed by bridge building.

“That was fantastic,” Ken said. “We were trained in everything – explosives, bridge building; the lot.”

Wagga Wagga, NSW: Trainees at the Royal Australian Engineers Training Centre, Kapooka Army Camp, cross a cable bridge under attack from low flying aircraft.

He was serving as a sapper with the 2/5th Field Regiment, when he sailed for Morotai on board USS General Anderson in June 1945.

“It was one of those Liberty ships,” he said.

“They had brought out the [Women’s Army Corps] from America, and then picked us up to take us to Morotai, and you wouldn’t believe it – the perfume.

“They hadn’t aired it or anything, and going into the tropics you couldn’t hardly breathe, so we slept up on deck.

“It was absolutely shocking; we opened all the ports and that, and somehow got rid of it… but it was really powerful.

“They didn’t have time between dropping off the girls and sending it up to us… so they just dropped the girls, and then picked us straight up and took us to Morotai…

Morotai, 9 June 1945: Members of the 2/4 Field Regiment crowded aboard the United States Landing Ship 1308 for their transport to Red Beach. They have just disembarked from the USS General Anderson after their journey from Australia.

“We formed up there for the landing at Balikpapan, and it was just one great long line of ships. You couldn’t see the end of it, it was that long…

“It was a pretty rugged sort of a place, Balikpapan, and it was pretty badly knocked about with the naval guns, but the Japanese had naval guns of their own up in the hills.

“They had one lot there where they could look out from a peep hole and shoot out to sea, but they managed to knock that one out.

“The engineers were able to get up there and blow it up, but there was another one on a hoist sort of a thing that they’d tried to erect out in the open.

“That was all up in the hills in a high spot, and fortunately we were able to get them before they got going…

Balikpapan area, Borneo, 7 July 1945: A Japanese 155mm naval gun used for coastal defence at Stalkudo, a former Dutch position. It was found by members of the 7th Division.

“But the explosions were the worst, where the minefields were laid, and things like that.

“The Japanese would set booby traps, and we would set ours at night, and in the morning they’d have gotten rid of ours, and put their own in. You wouldn’t believe it. And that was frightening.

“But in Borneo, they also got into our tents.

“A couple of Japanese shot every second person in the tent one night, and of course, they had to double the guards everywhere after that, but they got in and out without being caught and they didn’t ever find them …

“Then another time, a couple of young ones got shot through the stomach. One of them was the best rifle shot ever himself, but he got shot. And those sorts of things, you never forget; young, physically fit people who don’t come back.”

Balikpapan, Borneo. 26 July 1945. Australian engineers at work repairing the wharf and pipe line. Note the damaged jetty in the background.

Balikpapan, Borneo. July 1945. The Bailey Bridge which was erected by Australian engineers in a few hours to enable supplies to be transported to forward areas. During their retreat the Japanese endeavoured to hinder the Australian advance by blasting bridges. Debris can be seen in the foreground.

Ken was at Balikpapan when the war finally ended. He was still only 21.

“Oh, it was great,” he said.

“But your life was still on the line … The air force dropped literature to the enemy because there were still a lot of them around us in Borneo, but they wouldn’t believe it …

“They were still shooting at you because they thought it was a hoax… so we still had to go and physically take it to them.

“We built a compound [for] the Japanese prisoners … and I remember one of their chaps got appendicitis.

“It was pretty primitive, and they had him on a table outside.

“Their doctor was going to operate on him, and our doctors offered to do it for them in the compound, but they wouldn’t allow them to.

“They did this chap without any painkillers or anything, and he died in front of them….”

Balikpapan, Borneo, 10 September 1945: Surrender of all Japanese forces in the Balikpapan area at the 2/1st Pioneer Battalion headquarters, Tempadoeng.

Balikpapan, Borneo. c. 15 August 1945. Children swarm around 7th Division troops at Baroe village markets when sweets are distributed following the news of Japan's surrender.

Ken finally returned to Australia in February 1946, and was discharged in July.

“My dad was a teacher at Korrong Vale, and I was walking along up from the train, up to the house at the top of the school, and I saw this girl coming along,” he said.

“It happened to be my sister. She said, ‘Don’t you know your own damn sister?’

“She was coming down to the train to meet me, and she’d changed that much… I couldn’t believe it.

“She was only 14 or something when I left, and here she was, wearing this beautiful dress, and a big sun hat.”

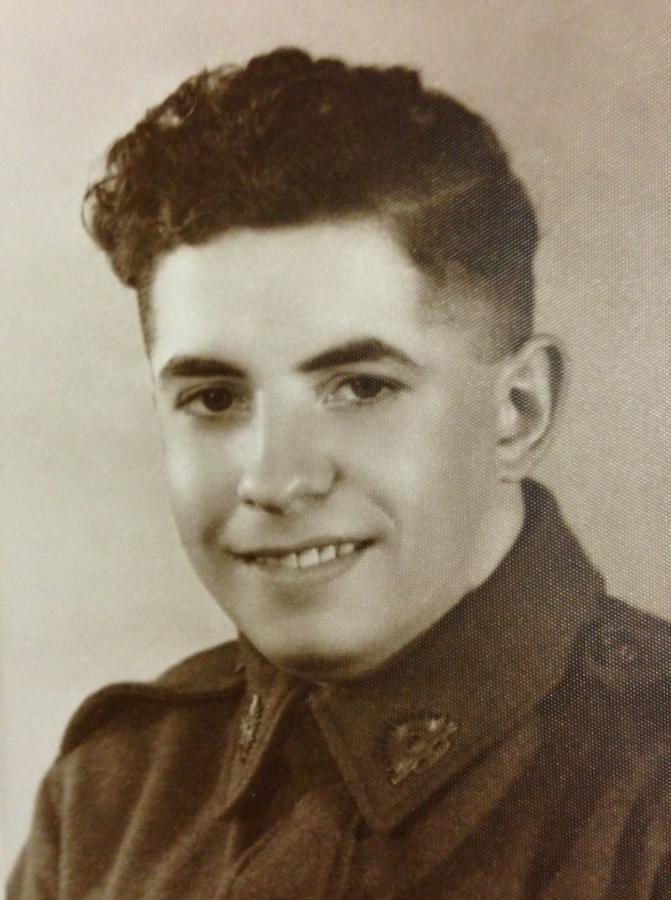

A 19-year-old Ken Keamy during the Second World War. Photo: Courtesy of Ken Keamy

Ken returned to his old job in Melbourne after the war, but later quit and went to work for the Repatriation Commission. He moved to Canberra in 1974, and worked for the renamed Department of Veterans Affairs until he retired in the 1980s.

Each year, on the anniversary of the landing at Balikpapan, he visits the Australian War Memorial to remember his mates.

More than 75 years later, he still considers himself fortunate to have survived.

“As a young person, it was a shocking thing to happen,” he said.

“It never goes out of your mind … certain things that happened when you nearly lost your life …

“I still think at times how lucky you were … lucky to be alive … the things that happened … when your mates are gone, and you survive …

“You never forget those things … It is something that will always be there.”