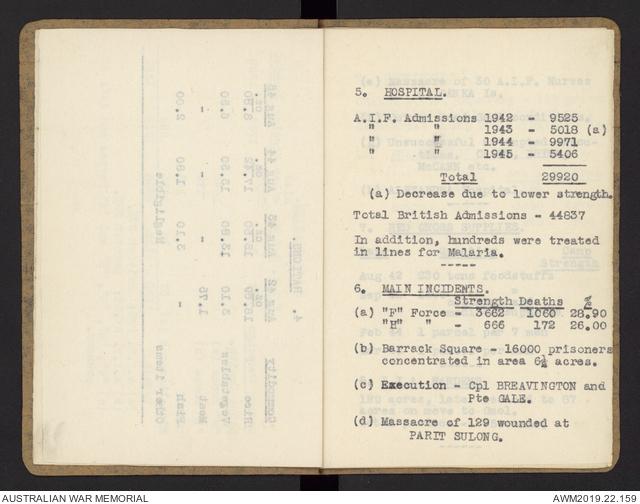

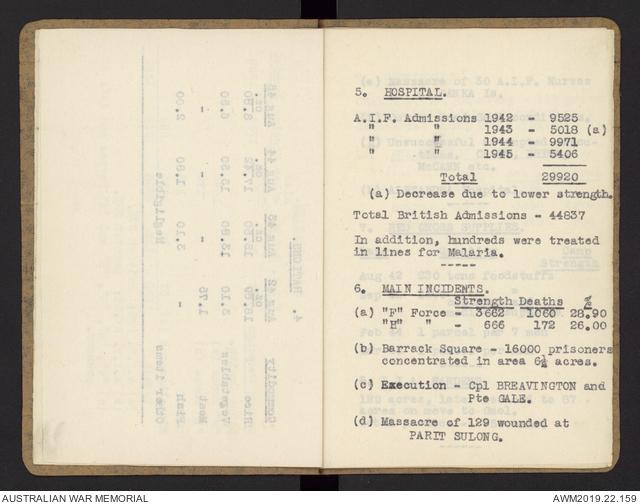

Brigadier Galleghan’s notebook contains an entry noting the execution of Corporal Breavington and Private Gale.

75th anniversary of the liberation of Changi

Today marks the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Australian prisoners of war at Changi. While many Australians know of the heroic deeds of Weary Dunlop, the illustrious and indefatigable surgeon who assisted the wounded and dying, less will know of Corporal Rodney Breavington, who was executed on 2 September 1942 at Changi Beach for trying to escape. British and Australian officers witnessed the execution; they later wrote that Corporal Breavington faced death with remarkable fortitude.

Changi, Singapore, 1945. A group of prisoners of war photographed at Changi prisoner of war camp shortly after the surrender of the Japanese.

On 12 May 1942, Corporal Breavington and Private Victor Lawrence Gale escaped from the Japanese prisoner of war camp at Bukit Timah, not far from Changi. An eyewitness account mostly likely written by Captain Norman Gilmour Macauley states that the escapees had found a small boat and after several days at sea were found on a nearby island, malnourished and in need of urgent medical attention. They were taken to a military hospital on Davao Island and later transferred to Changi.

On 1 September, Private Gale was discharged from hospital. Shortly afterwards Corporal Breavington, who was still unwell, was told to report to Lieutenant Okasaki, the camp commandant. Lieutenant Okasaki informed Corporal Breavington that he was to be handed over to the Indian garrison. The India garrison, which had aligned itself with the Japanese in the hope of gaining assistance in their pursuit for independence from British colonial rule, was to carry out orders to execute Breavington, Gale, and two other British soldiers.

Lieutenant Colonel Frederick “Black Jack” Galleghan, who was in command of the Australians at Changi, was ordered to gather a group and meet at the gates of the 18th Division. He was then told to walk towards Changi Beach.

When he arrived at Changi Beach he found Corporal Breavington, Private Gale and two English soldiers gathered in a group with the Indian garrison, and was told that he was to witness an execution. Galleghan watched as the men were ordered to face the firing squad with their backs toward the sea.

Corporal Breavington pleaded with Lieutenant Okasaki to spare Private Gale’s life. He told Okasaki that Gale was innocent, and had only followed the orders of his superior. But his pleas fell on deaf ears. Breavington asked a chaplain for a copy of the New Testament, so that he might read a passage to the men.

Breavington, Gale and the two British soldiers were ordered to stand apart. Lieutenant Okasaki offered Breavington a blindfold, which he refused. The others also refused the blindfold. An eyewitness recounts what happened next:

“Lt Breavington called to the firing squad and indicated on his own body where they were to aim. Lt Okasaki gave the order to fire. The four men fell. Breavington sat up and said, ‘You have shot me in the arm, please shoot me [through] the heart.’ The Indian Captain and another member of the [firing squad] fired again and Breavington was hit in the leg. He said, ‘For god’s sake, shoot me through the heart.”

The firing squad fired at the men up to eight times before moving closer and shooting them a further five times. Lieutenant Okasaki turned to the party and addressed them through an interpreter:

“You have just witnessed the executions of men who tried to escape contrary to orders. It’s impossible to escape as the great army covers all countries in the south. Anyone escaping from here must and will be brought back and put to death as you have just seen. We don’t want to put them to death. You have not signed this paper, which is an admission that you still intend to escape.”

Photograph taken during the Selarang Barracks Square Incident when Japanese General Fukuye concentrated 13,350 British and 2,050 Australian prisoners of war because of their refusal to sign a promise not to escape. The picture shows external excavations for latrines made necessary because of overcrowding in the barracks.

Lieutenant Okasaki hoped that the executions would demoralize the 15,000 or so Australians who, a few days earlier, had been herded into the small parade ground at Changi’s Selarang Barracks for refusing to sign a pledge promising not to escape. The Australians would hold out for another few days before they were instructed to sign the pledge by senior officers, concerned that unsanitary conditions would lead to further deaths from diseases.

The liberation of Changi was a day of jubilation for Australian troops and their families. It was also a day to mourn, and to remember the courage and bravery of their loved ones who died needlessly at the hands of the Japanese. Corporal Rodney Breavington was Mentioned in Despatches in 1947. Though he did not return to his family and to the community he served as a policeman in Victoria, we remember the sacrifice he made for his country at the Australian War Memorial.

Further information on collections referenced in this article and recently digitised collections relating to the experiences of Australian prisoners of war at Changi and other camps in Singapore and Malaya is available here:

RCDIG0001290 - Eyewitness account of the executions of Corporal Breavington and Private Gale, c.1942

PR04859 – Walton, Pierre Michael

3DRL/2191 – Galleghan, F G (Brigadier, DSO, OBE, ED, 8th Australian Division and POW)

PR84/074 – Madden, James Ross Harrington (Private, 2/30th Battalion AIF)

PR86/174 – Watson, Cyril John (Lieutenant, 4th Anti-Tank Regiment AIF, POW)

PR86/211 – Mills, Roy Markham (Captain, 2/10th Australian Field Ambulance AIF, POW)

PR89/099 – Leggatt, William Watt DSO MC (Lieutenant Colonel, 1894–1968)