Lindsay Walker: 'It was just unimaginable grief'

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people please be advised that the following article contains the names of deceased people.

Lindsay George Walker. Photo: Courtesy Thos Hodgson and the Goldspink family

It was September 1944, and Lindsay Walker was flying low over the mountains in Britain. It was supposed to be a routine training exercise. And then the weather turned bad. Walker’s bomber crashed into a mountain, killing all five crew-members on board.

His mother collapsed at the door of their family home in Sydney when she received the news.

Today, Lindsay Walker is the second known Aboriginal man to have died while serving in the Royal Australian Air Force during the Second World War.

But for years, his Indigenous heritage remained unknown.

Lindsay George Walker was born on 15 July 1923 in Cumnock in the New South Wales Central Tablelands, the only son of mechanic Nathaniel Parton Walker and his wife Mary Amelia Goldspink, a Burramatta woman of the Dharug (Eora) nation.

Mary’s grandmother, Margaret “Peggy” Reid, had been removed from her family at Kissing Point, on the Parramatta River, near Ryde, and had been placed in the first Native Institute, which later became the Parramatta Girls’ Home.

She was “put into service” at the age of 12 or 13, and at 19, married Jonathan Goldspink, a convict from Norfolk, England, who had arrived in Sydney Cove in 1826.

They had 14 children together and went on to own Beago Station at Tumbarumba on the western edge of the Snowy Mountains, before retiring to Yass.

A “capable, educated woman of considerable influence”, Margaret continued to manage several properties after her husband’s death in 1876.

When Margaret died in 1898, she was buried beside her husband, but because she was Aboriginal, she was not allowed to have any gravestone or inscription.

More than 30 of their descendants would go on to serve during the First and Second World Wars.

Lindsay Walker was one of them.

Lindsay Walker enlisted when he turned 18. Photo: Courtesy the Goldspink family

Affectionately known as “Wiz”, Lindsay grew up in the northern suburbs of Sydney, where he attended North Sydney Junior High School and then Fort Street Boys High School. A renowned sportsman, he particularly enjoyed swimming, athletics, and playing cricket.

By the time war broke out in 1939, Lindsay was working as a salesman at the Woolworths store in Sydney, and living at the family home, ‘Strathisla’, in Kirribilli.

His mother was devastated when he enlisted in the RAAF in June 1942, aged 18. Her brother, James, had been killed in France during the First World War and she knew all too well the pain and grief caused by war.

Her only son Lindsay went on to train at Bradfield Park, Narrandera and Point Cook, before qualifying as a pilot in April 1943.

He embarked for overseas service two months later, and arrived in Britain in September 1943. He would never see his family again.

On 3 September 1944, Lindsay and his crew took off in their Halifax bomber on an operational training flight to undertake a standard navigational exercise over the western regions of Wales.

The Halifax and its five-man crew left the base at 11.30 am and were due at Strumble Head, South Wales, by about 2.30 pm that same afternoon.

When the aircraft failed to arrive, it was discovered that it had crashed into the Rival Mountains, south of the town of Trevor. There were no survivors.

An investigation into the crash later revealed that the Halifax had last been seen flying low in heavy rain and mist.

The crew had been instructed to turn back if the cloud cover impaired visibility or became too thick, and had been trying to navigate by visual aids along the Welsh coastline, flying low in mountainous country, when the crash occurred.

Lindsay and his crew were buried with military honours in Cheshire, England, on 8 September 1944. Before his funeral, the squadron’s chaplain wrote to Lindsay’s mother, saying: “It may be of some comfort to you to know that your son’s death was instantaneous and that he died whilst flying in the service of his country.”

Today, Lindsay’s remains lie in Blacon Cemetery, Chester, beneath the inscription chosen by his family: “He gave his life that those he loved might live in peace.”

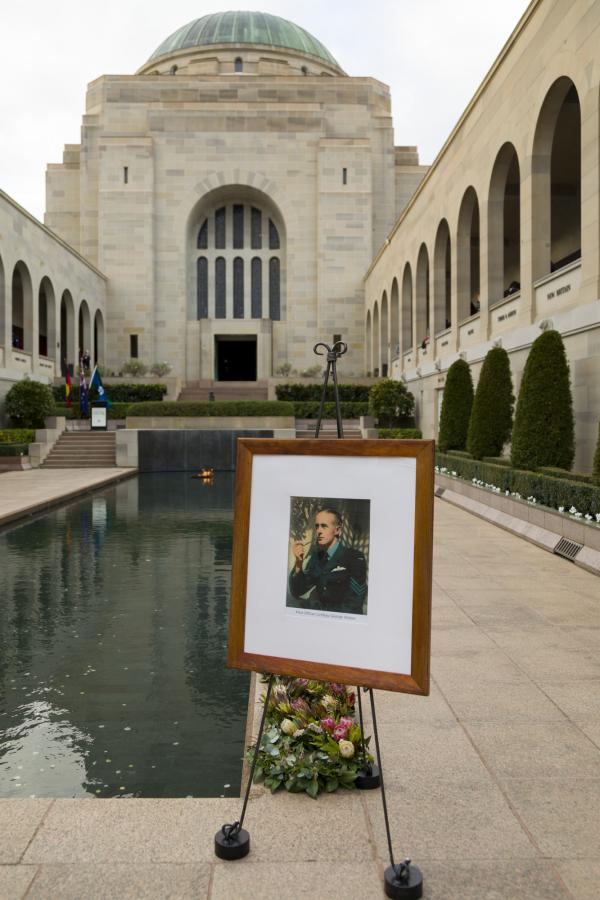

His nephew, Thos Hodgson, laid a wreath in his honour at a Last Post Ceremony commemorating his life at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

“When he volunteered, my grandmother was absolutely destroyed,” Thos said.

“She didn't want him to go, and she was just distraught when he was killed.

“They were obviously very proud of him, but my grandmother particularly, was just very, very concerned and worried the whole time that he was away that something would happen.

“And sadly it did.

“When the telegram came, my grandmother collapsed at the door.

“It was a bit like that scene with the mother in [the film] Saving Private Ryan when the car comes up [the drive].

“She at least was told by people in the military, but in those days [in Australia], it was just a telegram from the department to say that they had been killed.

“The telegraph boy would come on his bike and deliver the telegram and that was it.

“And then of course there was the letter that came later saying your son has died in the service of his country and to be proud of him, but I don't think that resonated particularly well with my grandmother.

“He was adored by my grandmother and my grandmother never recovered from the loss. Nor did my grandfather.

“He had such potential, and had a great future ahead of him.

“He was a real superstar from all accounts and was known as ‘Wiz’ or Wizard because he was good at whatever he put his hand to.

“My grandmother never really got over it.

“She never wanted to look at the photographs that people sent back of the funeral or the salute.

“The whole crew was killed, except for one guy who was sick on the day and didn't go.

“They’re buried in Blacon Cemetery, and when I went over to England in the early 1970s, I visited the cemetery and put some flowers on his grave and on the graves of the others.

“The cemetery is beautifully kept and maintained by war graves and it was a very special thing to be the first person in the family to go there.

“Even though I didn’t know him, the whole thing was very emotional.

“It was just such a sad loss of such a young man, and the impact of that on the family, particularly my grandmother, and then my mother.

“It was just unimaginable grief, and I don't think I don't think either of them ever really recovered from it.”

Thos’s mother was just 10 years old when her brother went to war and never came home. Years later, she would suffer another devastating loss.

Thos’ father, Thomas Ernest Ellison Poole, served as a pilot in the RAAF during the Korean War and was working for Qantas when he was killed in an accident at Guam before Thos was born.

Thos’s mother had been married for just 15 months when his father died. The news of the accident arrived on the eighth anniversary of her brother’s death.

“He died on 2 September 1952, a day before the anniversary of my uncle’s death on 3 September 1944,” Thos said.

“My mother was still only young. She was only 19 or 20 when my father was killed, so it was a very sad time for her, losing her brother at age 21, and then her husband at age 27.

“It was just an enormous burden to bear for someone so young.”

Lindsay George Walker was buried at Blacon Cemetery. Photo: Courtesy the Goldspink family

The family renamed their home at Kirribilli, ‘Lynellis’, in honour of Thos’s father and uncle.

Today, Thos has their uniforms as well as a Morse code set that his uncle made during the war.

He only learnt of his family’s Indigenous heritage recently.

“I don't know to what extent Lindsay would have even known that he was of indigenous descent because I think it was something that was kept pretty quiet,” he said.

“In those days, there were issues about whether or not Indigenous people could marry white people, and there were certainly issues of prejudice and all the rest of it.

“Now, it’s something that would be embraced, but back then in the 30s, or the 20s even, it was something that was seen as some dark secret in the family that people wanted to remain secret.

“I didn't even know about it for a long time.

“My grandmother never wanted to have any photos taken, and it's only been by putting two and two together that we started to work it out.

“When I first found out about it through the cousins, I thought it was another scandal … a baby born out of marriage … or one of the forebears who came out as a convict…

“There was no link to the Indigenous marriage to Margaret, or Peggy as she was known. I was not even aware of that until the last five years or so.

“There was a lady who did genealogy down at Bowral and I [asked her] to look into my family tree … and then suddenly it all came together…

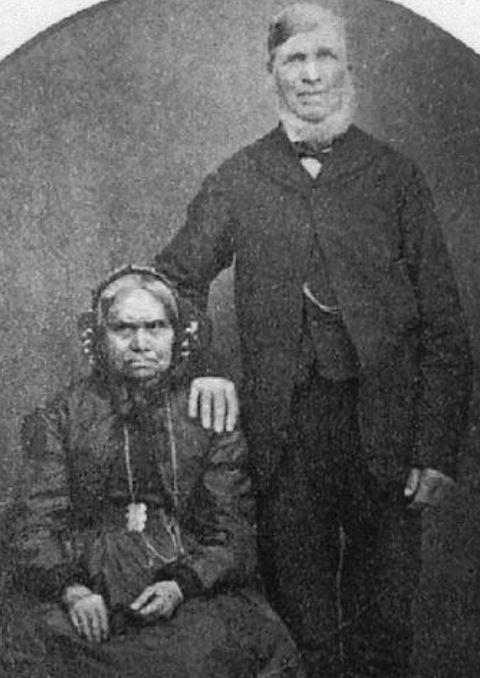

Jonathan and Margaret Goldspink. Photo: Courtesy the Goldspink family

Margaret Goldspink, seated, with members of her family. Photo: Courtesy the Goldspink family

“Sadly, my grandparents never got across to see my uncle's grave, because you just didn't you just didn't travel in those days.

“But when my mother and my step-father went to England in the late 1970s, she contacted the postmaster at Sudbury in Suffolk to see if anyone remembered her brother.

“She was able to meet with people who had been in the house where he was billeted for a period of time, and that was quite an amazing sequel 30 years later.

“He was still remembered, and remembered very fondly, and they became friends of my mother's, which was particularly special for.”

Thos laid a wreath at the Last Post Ceremony commemorating his uncle’s life and placed a poppy by his name on the Roll of Honour.

“It's an honour and a privilege and I'm so pleased that my uncle is being recognised,” he said.

“They lived down at Kirribilli … under the shadows of the newly constructed Harbour Bridge …

“And at 21, he was captain of a bomber plane, which is pretty amazing in itself.

“He was just a great all-rounder, and he was good at whatever he did, but obviously he had the moral courage to say, ‘I've got to go and join up and I want to join the air force.’

“He obviously wanted to serve and wanted to contribute, and that was a very brave thing to do.”

“He was such a special young man, and to have him honoured in this way is particularly special.

“I only wish my mother and my grandmother could have been there, but I'm sure they were there in spirit.”

Michael Bell is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial. A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, he is working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au