The Last Letters of Matron Irene Melville Drummond

In November 1940, Irene Melville Drummond, a nurse from Broken Hill, NSW, enlisted in the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) to provide care to wounded and sick soldiers amid the turmoil of the Second World War. Appointed to the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station, she soon embarked on the converted cruise liner Queen Mary, bound for Singapore. There she began her duties and for a short period transferred to the 2/9th Field Ambulance. On 5 August 1941, Irene was promoted to matron and posted to the 2/13th Australian General Hospital, then stationed in an incomplete hospital in Johore Bahru, Malaya.

Matron Drummond was one of the 21 Australian Army nurses to be horrifically executed by the Japanese on Radji Beach during the Banka Island Massacre on 16 February 1942.

The sole survivor of the massacre, Lieutenant Colonel Vivian Bullwinkel, who was a close friend to Irene, reported that she was one of the first to be shot and killed that day. As the nurses walked into the sea, where they would be executed by machine-gun, Matron Drummond uttered her final words: "Chin up, girls. I'm proud of you and I love you all."

Vivian and Irene first met in 1935 at the Broken Hill and District Hospital while Vivian was training under Irene’s mentorship.

The Australian War Memorial holds a Private Records collection containing two letters that Matron Drummond wrote to her family months before this event.

In her first letter, dated 17 December 1941, Matron Drummond wrote to her sisters, Phyllis and Ruth, to reassure them that she was “well and safe” and update them on life during the war: “Our hospital grows bigger daily and a tremendous lot of work has been done during the last ten days. We are in the throes of a thunder storm at present and my tent is not very water proof though it has the advantage of being cool and I get a breeze. I really don’t mind if the rain continues as it gives us a quiet night from air raid alarms as visibility is bad with the heavy clouds about.”

Irene also thanked her sisters for sending a parcel of books, mentions blackouts being the “bane of my existence”, the pausing of cables until after Christmas, and described how the blue air mail paper and kerosene lamps made a terrible combination for writing at night. Near the end of her letter, she includes a joke, and a closing remark: “Well I can’t recommend this paper to anyone but as I have said before it is an uncomfortable war and I suppose we’ll have to put up with it.”

At the time of the letter, Japan had just invaded Malaya and the Fall of Singapore was looming.

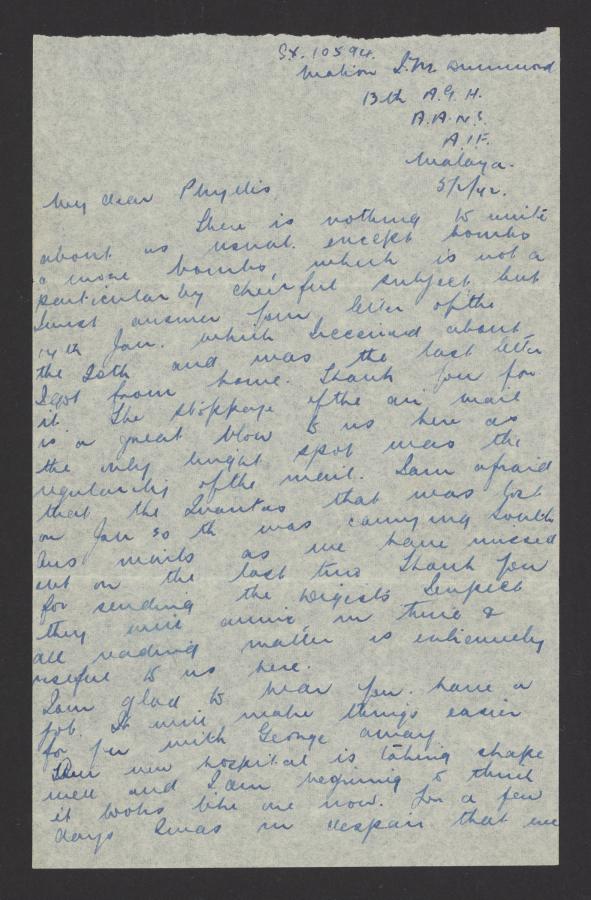

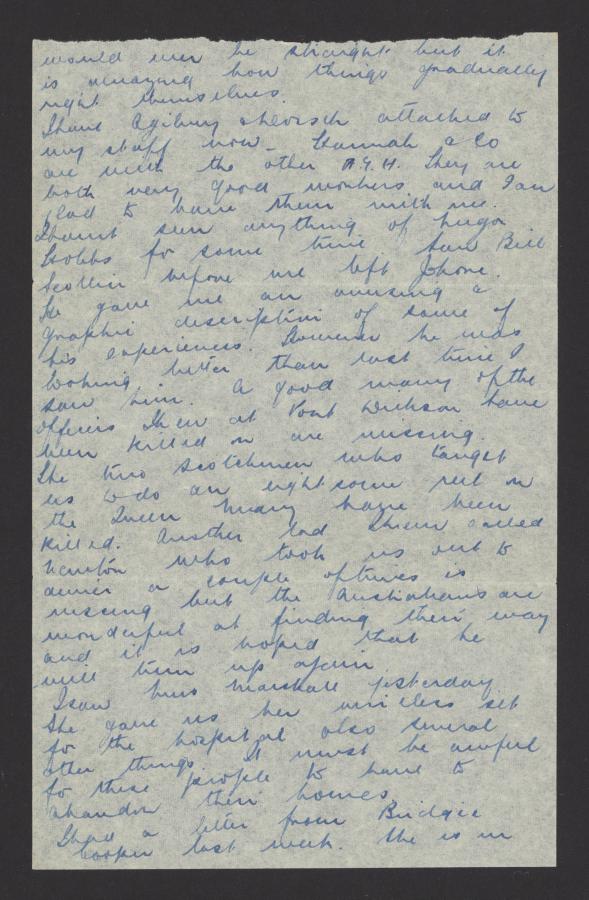

On 5 February 1942, just days before Matron Drummond and the remaining Australian Army nurses were ordered to evacuate Singapore aboard SS Vyner Brooke, she wrote another letter to Phyllis. This time discussing the increasing challenges they faced: “There is nothing to write about as usual. Except bombs and more bombs which is not a particularly cheerful subject … The stopping of the air mail is a great blow to us here, as the only bright spot was the regularity of the mail.”

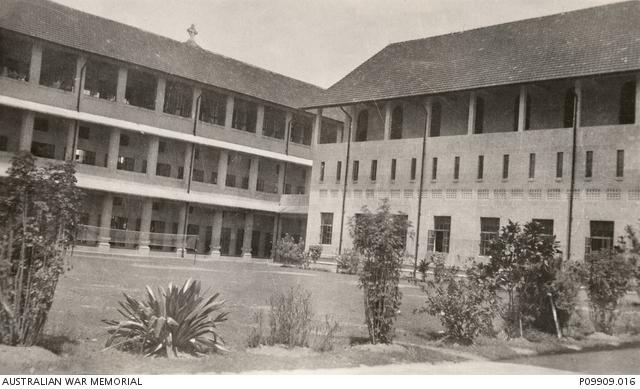

As the rapid Japanese advance towards Singapore caused British forces to withdraw through the Malay Peninsula and onto Singapore Island, the hospital was quickly moved to St Patrick’s School in Singapore. Matron Drummond helped to organise the new hospital, which contained 700 beds, within 38 hours, she writes: “Our new hospital is taking shape well and I am beginning to think it works … now. For a few days I was in despair that we would never be straight but it is amazing how things gradually right themselves.”

St Patricks School, Singapore, 1941. P09909.016

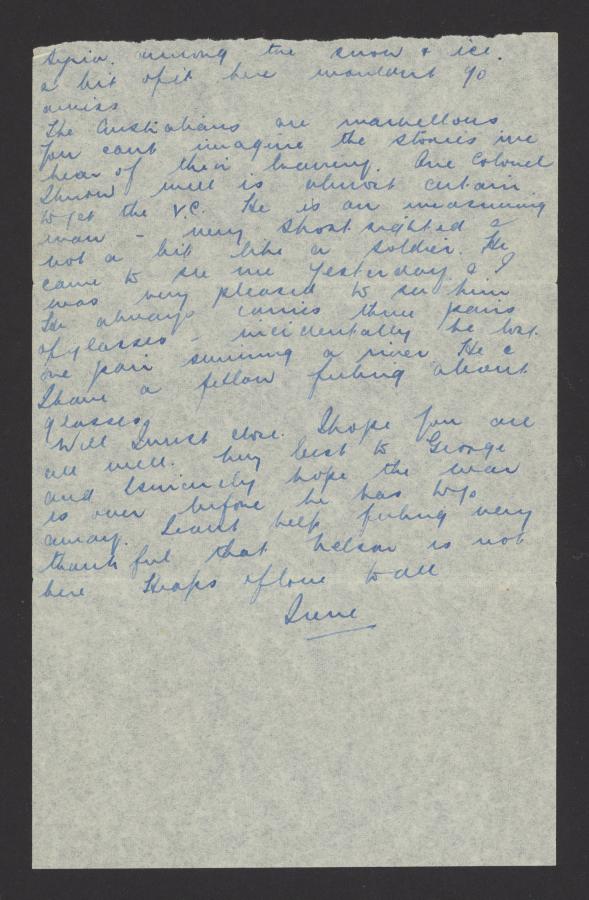

The second letter mentions the ship that was likely carrying mail for her going missing, and hearing news of officers and friends being killed or reported missing. She also writes of the brave Australian soldiers she had encountered: “The Australians are marvellous you can’t imagine the stories we hear of their bravery. One colonel I know well is almost certain to get the V.C. He is an amazing man – very short sighted and not a bit like a soldier ... He always carries three pairs of glasses – incidentally he lost one pair swimming [in] a river. He and I had a fellow fishing about [for the] glasses.”

Irene’s ability to remain positive through such a trying time is clearly displayed throughout her letters and echoed in her final words.

The Research Centre has recently digitised Matron Drummond’s letters, held within the Private Records collection PR87/187 which will be available online soon and can be viewed in the Charles Bean Research Centre.