'Yarning is where we connect... to listen and understand.'

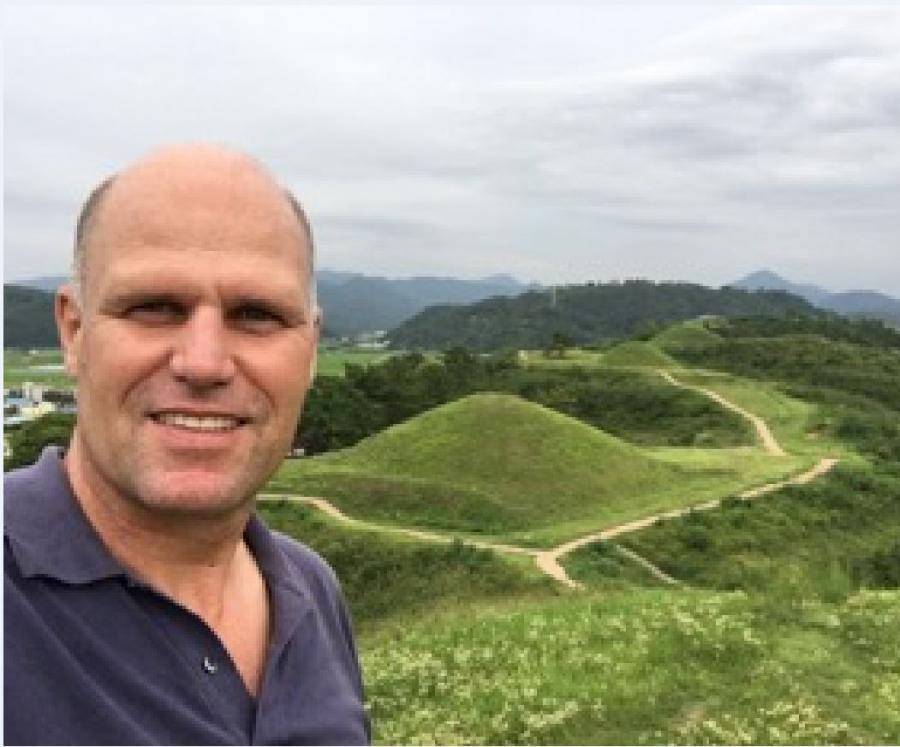

Conceptual artist Matt Jones is the winner of the 2020 Napier Waller Art Prize, for his work Yarn.

When Matt Jones found himself homeless in Sydney, camping on friends’ couches and sleeping on trains, he never dreamt that he would one day win a national art prize for veterans.

But that’s exactly what happened.

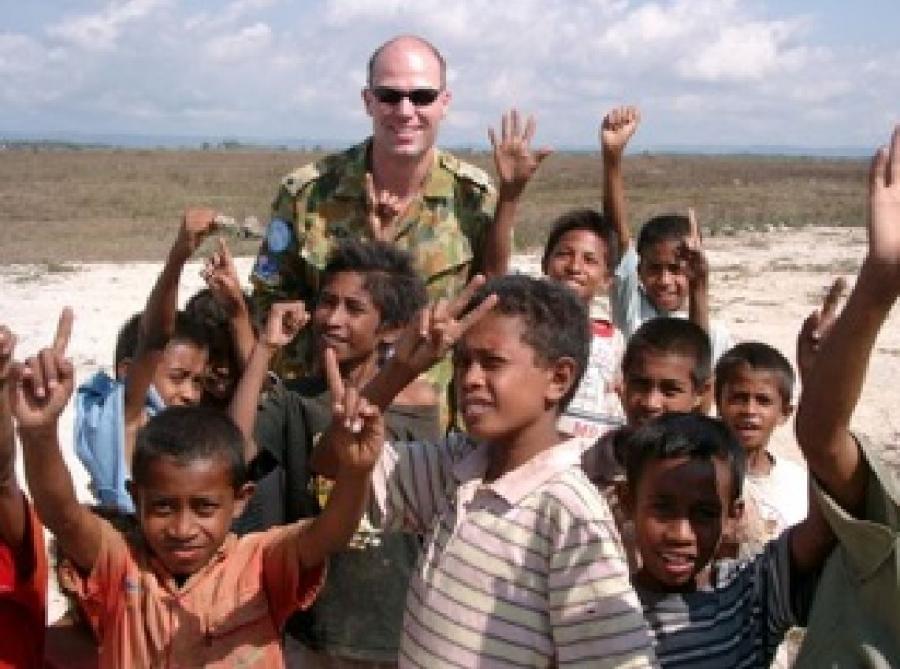

A former army major from who served in East Timor, Matt is the winner of the 2020 Napier Waller Art Prize for his work Yarn.

For conceptual artist Matt Jones, yarning is all about connection and telling stories that need to be told.

“I’m absolutely stoked,” he said. “When I was told, I felt a bit numb actually. It’s still sinking in exactly what it means … but it’s been great.

“It’s a vindication of the difficulties that I’ve been through; that it was worthwhile telling the story, even if I’m the only person who knows what that story is.”

Matt’s work Yarn was selected from a short list of 17 Highly Commended entries. He will receive a $10,000 cash prize, and his art work will be displayed at the Australian War Memorial and accessioned into the National Collection. He will also receive a two-week research residency in the Art Section of the Memorial, and a mentoring day with eX de Medici, former official war artist to the Solomon Islands.

The inspiration behind Matt’s work, made from yarn and recycled fabric, comes from the blue and yellow maritime signal flag, Kilo, meaning, “I want to communicate with you.”

Matt Jones's work Yarn, 2020, yarn, recycled waste fabric, 183 x 183 x 18 cm.

For Matt, it is deeply personal.

“To say it hasn’t been an easy journey for me after leaving the army would be an understatement,” he said.

“It’s been really difficult in a whole range of ways, and I’m on the other side of the breakers now as I swim through the surf.

“But at one point in time I found myself homeless. I was managing a fairly intricate game of smoke and mirrors, and sleeping on friends’ couches. They knew something was going on, but they were giving me space and allowing me to maintain a sense of dignity by not saying, ‘What’s going on, mate?’”

He would sleep on the evening train from Sydney’s Central Station to Hamilton near Newcastle or to the Blue Mountains, and would have a swim at Manly in the morning to wash, so that it would appear that he was maintaining some semblance of a ‘normal’ life.

“It completely unsustainable and some friends worked out what was going on and they intervened,” he said. “Thanks to them, I ended up in a place for homeless veterans, which was a brutal assault on my pride.”

He wove part of a blanket he was given at the time into his prize-winning work.

“It was a blanket that had been made by a local knitting group and I really value it,” he said. “But while making the work I was looking for some more material to put into the blue section, and it dawned on me that I wanted to cut up part of that blanket and make a declaration to say that part of my life was well and truly behind me. So I wove it into the material to give it some form, but also to make sure that the blanket wasn’t coming back.

“That’s why that story is there and there’s a sort of a triumphant nature in having that story presented on a public stage. For me, I’m saying, I’ve moved on from there.

“All that difficulty is behind me, and in some respects that is captured in the rawness of the work.

“It’s me taking the initiative; I’m going to disclose some things about myself that I think are probably not my best moments. So the raw and raggedy aspect of the work is to say, it’s a little bit of a bumpy ride for not only the person telling the story, but maybe for the person who is listening as well.

“There have been times when I didn’t want to communicate. I didn't want to admit to the difficulties I had encountered. I felt I didn’t have the language to describe the sense of shame that I could neither name nor admit to experiencing.

“The act of making this oversized signal flag is a declaration that I wish to leave the messiness of the past behind me. It’s time to pick up the loose threads and broken relationships, be they personal, societal or institutional.

“Unless we have the courage to show vulnerability in telling those stories, we are just going to dance around the issue.”

The dimensions of the work mirror his height and arm span, creating what he describes as an unorthodox self-portrait.

“Alienation is the idea at the heart of this artwork,” he said. “When you alienate yourself from yourself or from other people, it is not productive at all. You can be as tough and strong as you want to be, but you are basically driving with at least one flat tyre, and it’s not pretty.

“The materials used are unapologetically crude, gathered while I had an opportunity between a period of quarantined self-isolation after returning from Korea, and the subsequently imposed national lockdown.

“The work itself took about six weeks, and for the last three weeks it just consumed me.”

Matt Jones joined the army in 1988. He graduated from RMC Duntroon in 1989 and served in East Timor in 2002.

Matt had originally planned to create the work using blue and yellow milk crates or boxes, but was taken with the colours of the yarn he discovered at a fabric store’s closing down sale in Sydney. He then taught himself how to weave and knit during the Covid-19 lockdown.

“We tell our stories with what we have, not with what we hope that we might have,” he said.

“I was taken with the fact I was hiding stories through the fringe of loose yarn that hangs across the front, and that across the back of the panel there is this sedimentary layer of stories.

“There was this hidden nature to the work, and a rawness – an unfinished nature – which is speaking to this aspect of a reluctance to really fly that flag – ‘I want to communicate with you’ – stepping out of that sense of alienation, and stepping out of the cloud of shame.

“I think there is a necessity for me to somehow tell those stories if I’m serious about helping other people. I can’t identify as that person, but I can find strength in somehow sharing that story for the benefit of others, so for me that is the very real rawness of the signal flag, ‘I want to communicate with you.’

“I’m ready to face up to the reality of where I’ve been and where I’m going now, whereas in the past when I was masking that and not being honest with my mates, I wouldn’t communicate those things, so that’s the message behind it and what’s at the heart of it.

“It is difficult to draw out those things, but it is important to talk about them.

“It’s great seeing the transformation of what were once separate balls of fabric into something that appears to be a panel – two panels that are one whole panel of integrity – but is actually an assembly of individual strings or individual bits of yarn.

“We all know the word yarn – to have a yarn, to talk, to tell stories – so I thought it was a very interesting sort of play on words.

“This work is made up of a whole lot of individual pieces of yarn, and there are a whole lot of stories from myself that have gone into it, so the threading together of those stories is the therapeautic nature of it.

“You have these things between your fingers, and you feel the different textures of the fabric, and you have to knit it together and work out how those things hold – and that’s all part of it. There’s even the comfort in the softness of the material...

“Yarning is where we connect. To listen and understand.”

The 17 Highly Commended works in the 2020 Napier Waller Art Prize will be on display in the Special Exhibitions Gallery at the Memorial until 22 November 2020. Voting for the People’s Choice Award will continue via the Memorial’s website until the exhibition closes.