'It’s probably the most challenging thing I’ve ever done'

Official war artist Megan Cope.

Photo: Jo-Anne Driessens

When Indigenous artist Megan Cope was asked to be an official war artist, she thought of her Uncle Dick, who was killed during the First World War.

Her great-great uncle, Private Richard Martin, enlisted in December 1914, but had to lie about his ancestry to do so.

As an Indigenous Australian, he was not eligible to join the Australian Imperial Force, so he claimed he was from Dunedin in New Zealand, and that he had served in the Light Horse for five years.

But none of it was true. Martin was, in fact, born on Stradbroke Island, and had no known previous military service.

He went on to serve on Gallipoli and the Western Front, enduring the costly battles at Bullecourt, Messines, and Passchendaele for a country that didn’t even recognise him as one of its own.

He was wounded in action three times, and was killed in March 1918 while defending Allied lines near the French village of Dernancourt.

Almost 100 years after his death, his great-great niece, Cope, a proud Quandamooka woman from Minjerribah, became the first female First Nations official war artist at the Australian War Memorial.

Megan Cope's great-great uncle Private Richard Martin. was killed during the First World War.

“It’s probably the most challenging thing I’ve ever done,” Cope said.

“When I first got asked, I immediately thought of my family’s role in the military in [the First and Second World Wars] and my living relatives, particularly my grandmother and my great-aunty, who are particularly proud of their grandfathers and great uncles who served.

“I saw it as a way to continue that respect and honour … I spoke to my grandmother, and she agreed that it would be a great honour, and a great responsibility.”

Part social cartographer, curator, writer, and artist, Cope investigates issues of identity, colonisation, the environment, and map-making through her art practice, which also includes sculpture, video work, and painting.

“I’ve learnt a lot and I’ve felt a lot during this process,” she said.

“I guess I was in a bit of conflict when I was asked to do it because of the political nature of my work and how, in an Australian context, I’m talking about stories that haven’t been told, and are often yet to be unearthed, and yet to be positioned in their rightful place.

“I think it’s really important that war artists go to conflict zones and have this experience and spend time with soldiers and make artwork, because it enables other conversations and ways to talk about what’s happening in the world.”

Megan Cope has produced a series of works for the Memorial titled Flight or fight.

Photo: Jo-Anne Driessens

In 2017 Cope spent three weeks with the Royal Australian Air Force in the Middle East, and recently completed a body of work based on her experiences.

“I had been to Jerusalem before, so when I was invited to do this project I had already been interested in conflict and contested landscapes and places,” she said.

“But this was something completely different. Being on an airbase, seeing how everything works, how everybody works together, and even the architecture, and how people move through those spaces … was really fascinating to me.”

Much of her work was inspired by what she saw during a ten-hour flight on a KC-30 air transport tanker as allied jets refuelled mid-air.

“We flew up to the border of Syria and Iraq and Turkey, and I was very much interested in the flight path that we took,” she said. “All of the works that I’ve done have mapped those memories, and critical things in the environment that our forces have done, or are involved in.”

Megan Cope's work incorporates a range of historical maps. Photo: Jo-Anne Driessens

Her work incorporates a range of historical maps, including from the 1930s and 1940s, and the Sykes–Picot map of 1916. The Sykes–Picot map was the result of a secret agreement between Britain and France discussing the break-up of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War. Its ramifications continue to cast a shadow over the current conflict in the Middle East.

“The military relies on maps every day … [so] maps of this region are in all of the works,” Cope said. “Pilots who fly in the Air Force also carry maps with them in their emergency packs, and I was interested in that. These maps are made for every flight that they take, and no matter the conditions, if they have to land, they’ve got this, and will be able to find their way out … so I wanted to produce this map in a similar way [on silk as they did during the First and Second World Wars].”

Cope’s body of work also features a Chinese map of the region from the 1940s, and includes radar and communication symbols commonly used by the air force.

“All of those symbols were discussed and shared on that flight that we took in the KC-30,” she said. “They’re all symbols that the pilots have on their screens as they are flying … [and] I was really interested in how critical that language is.”

Megan Cope completed her work back home in her Country.

Photo: Jo-Anne Driessens

A green keffiyeh, a Middle Eastern head scarf that Cope kept with her during her deployment, becomes part of the landscape in one of her works, while in another, engine oil is used to mark the ancient Euphrates and Tigris rivers.

“I kind of wanted to make some subtle suggestions about oil,” she said. “I think that in general, it’s something that we need to start thinking differently about – our relationship to fossil fuels and our relationship to petro-chemicals and all of that kind of stuff.”

Cope used timber from Minjerribah – the traditional name for North Stradbroke Island – to make the maps look like the ones that used to hang in school class rooms around Australia.

“Kids today probably won’t ever know what those maps look like, but I really wanted the maps to have that weight … to reflect that time of when we are learning about the world,” she said. “For me, it was really important to present the maps like that, and … attach some of my Country to it.”

For Cope, who has been making art since she was a child, it was important to complete her work back home in her Country.

“I felt very grateful to be able to make the work there,” she said. “When I was a kid I used to paint on cornflake boxes, and whatever I could get my hands on. So from a young age, I’ve been active in painting and storytelling … It was important to me to be home, because the reason I was doing that is that there are a lot of people who don’t have their homes anymore.”

She would like her work to make people stop and think. “I’m really honoured to have my work here [at the Memorial],” she said. “I never would have expected it, to be honest, so I hope that people like them, and ask lots of questions, and look at different ways of seeing the Middle East … It certainly was a once-in-a-lifetime kind of experience.”

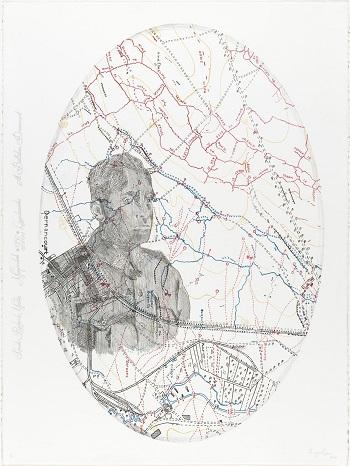

Cope's earlier work, Ngaliya barwon Gami (our great-uncle), focuses on the service of her great-great uncle, Private Richard Martin, and is part of the Anzac Centenary Print Portfolio. It features in the Memorial's travelling exhibition, For Country, for Nation.

Cope often works with military maps and was interested in the way people assign familiar names to foreign places, just as colonisers did for Aboriginal lands.

Cope had previously uncovered the histories of seven Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men from her home on Stradbroke Island who served in the First World War.

She searched through the archives of the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia, teasing out military narratives and mapping movements across different theatres of war.

She was interested in portraits of the men that her grandmother and great-aunts had often spoken about and locating them in the European landscape using military maps.

This was an important process for Cope, who noted that “not many people think about Aboriginal people being in Europe 100 years ago”.

Her earlier work, Ngaliya barwon Gami (our great-uncle), focuses on the service of her great-great uncle, Private Richard Martin, and is part of the Anzac Centenary Print Portfolio.

It is now part of the national collection and is on display as part of the Memorial’s touring exhibition, For Country, For Nation.

She hopes her great-great uncle would be proud.