"He taught us all how to die..."

Douglas Barrett-Lennard and the Western Australians of the 8th Australian Field Artillery Battery

Of such mettle were the men who, under the most insuperable difficulties of Anzac, fought their guns throughout the campaign.

C. E. W. Bean in The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918: Volume II, The Story of Anzac: from 4 May, 1915 to the Evacuation

When Charles Bean, Australia’s official First World War historian, wrote this, he was describing the Western Australian men of the 8th Australian Field Artillery Battery at Gallipoli. In particular, he was writing of the events of 17 July 1915, a day when the battery lost two of its own. Douglas Barrett-Lennard was one of them.

This is as much a story about him as it is about all of them.

Douglas Graham Barrett-Lennard was born on 27 May 1894 at St. Leonard’s (near Guildford) in Western Australia, the son of George Hardey Barrett-Lennard and Amy Drake-Brockman. The Barrett-Lennard family had a long established history in Western Australia. Douglas’ great-grandfather, Edward Pomeroy Barrett-Lennard, had been one of the early pioneers of the state. Edward had been one of the first settlers to arrive in Western Australia in 1829, where he had selected land on the banks of the Swan River on the site of the property which came to be known as St. Leonard’s. The land had been passed down to Douglas’ grandfather Edward and then to Douglas’ father George. George followed the agricultural pursuits of his forefathers, later specialising in viticulture, and was a key force in the foundation of the grape export industry in Western Australia. In 1886 George had married Amy Drake-Brockman, also from a family with significant lineage in Western Australia. Roughly eight years later, Douglas was born at St. Leonard’s, the fourth generation of the Barrett-Lennard family to call the property home.

As a youth, Douglas attended Guildford Grammar School just down the road and was a member of the school cadets during his time there. He was working at the family property when the First World War broke out in August 1914. Douglas decided to enlist soon after and made his way down to the military camp that had just been established at Blackboy Hill, which would become the birthplace of the Australian Imperial Force (A.I.F) in Western Australia, enlisting on 23 September 1914. The 20-year-old was assigned the service number 1879 and the rank of driver and was allotted to the 3rd Field Artillery Brigade (F.A.B).

The initial training in camp was mainly limited to marching, drilling, musketry practice and other basic military tasks. Finally, on 31 October 1914, Douglas embarked from Fremantle for Egypt aboard the troopship HMAT Medic. The 12,000 ton steamship had been called into service as a key troopship for Australia during the Boer War. Some fourteen years later the ship, having since served as a passenger liner on the Liverpool-Cape Town-Sydney route, was once again called into service. On board he found a menagerie of fellow servicemen. There was the West Australian contingent of the 12th Infantry Battalion, and men of the 3rd Field Artillery Brigade and 3rd Field Company Engineers. There were also men of the 3rd Field Ambulance, the Divisional Ammunition Column, and the 1st Divisional Train of the Army Service Corps. Once overseas they would become gunners, drivers, stretcher bearers, engineers and soldiers. All of them would feel the twin screws of the Medic churning through the water beneath them, taking the men further and further from the coast of Western Australia and towards the open ocean. At 4 p.m. on 3 November, after being escorted by the Japanese armoured cruiser Ibuki and the Australian light cruiser Pioneer, the Medic joined the rest of the convoy that had left from Albany and took up its place towards front.

In a letter to his father whilst aboard the Medic, Douglas comes across as a young man who is very eager to prove himself and join the action but who is also cognisant of his youth and inexperience. Resolving to try his hardest in any case he wrote:

There will probably be a military exam when we reach England and [I] am putting all my spare time into reading the subject up. There is a frightful lot to learn in so short a time and I will be competing against men who have had years of experience. I don’t think I have a possible chance of passing but am going to have a try if I get the chance. I have learnt to like this military life exceedingly but find myself frightfully handicapped in not having previous knowledge of the game and also my age is a great drawback. These old and proved soldiers despise we young bloods exceedingly so [it] makes it very hard to hold your own with them.

Letter from Douglas Barrett-Lennard to his father, [at sea], [1914]

After arriving in Egypt, Douglas was assigned to the 8th Battery of the 3rd F.A.B., an artillery unit consisting of men from Western Australia. In Egypt, he and the men spent their days in camp, training or sightseeing. While is Cairo one night Douglas shared a dance with a young French woman, although he didn’t consider himself a good dancer. In a letter to his mother he wrote:

She could not speak a word of English and you know what my poor old French is like, however I kept my eyes well opened and she was quite capable of showing me into the right place so I managed to scrape through after a fashion. These French are most graceful dancers and [I] am afraid I was very awkward and clumsy and my military bouts.

Letter from Douglas Barrett-Lennard to his mother, Mena Camp, [Egypt], 2 March 1915

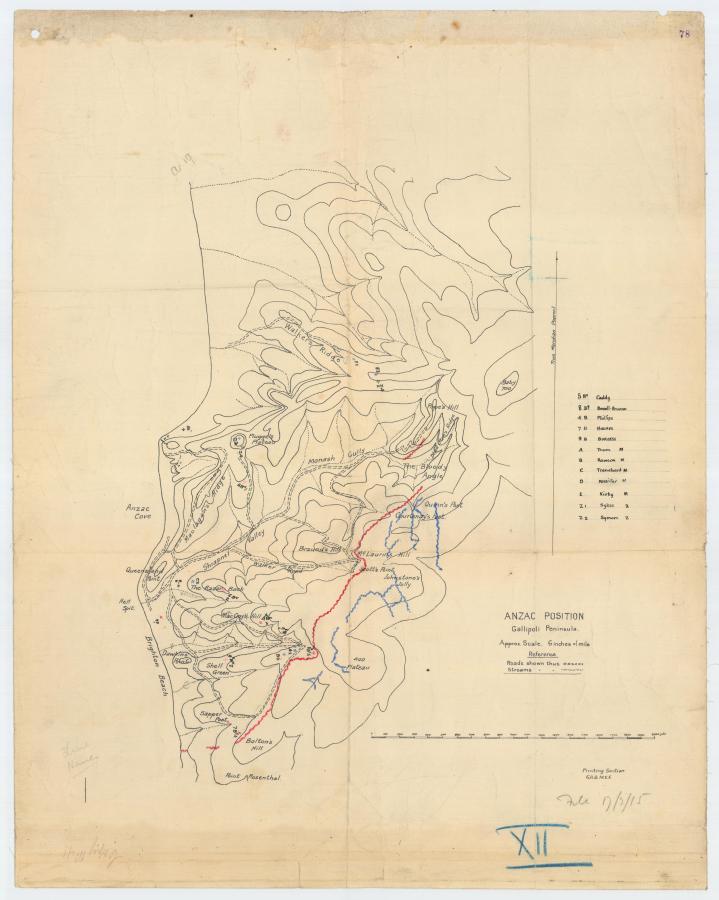

Positions of 1st Australian Divisional Artillery at Gallipoli, July 1915. The position of the 8th Australian Field Artillery Battery, under the command of Major Alfred Joseph Bessell-Browne, is displayed.

Douglas was eager to prove himself in action and he, along with many of the men, was beginning to feel restless in Egypt. He wrote: “None of us know a bit where we are going to and don’t much care either as long as we get some fighting somewhere.” Soon after, the 8th Battery was shipped out and by early May 1915 Douglas and the men found themselves at Gallipoli. The men soon found the action they had sought. In a letter to his mother on 13 May 1915, Douglas details that the battery was exhausted and fatigued after having been in action for ten straight days, under constant shellfire and suffering significant casualties. He also writes that the commander of the 8th Battery, Major Alfred Bessell-Browne, had previously encouraged him to become a gunner, rather than a driver, opening up the possibility of promotion. Douglas initially refused but upon realising that serving as a gunner would enable him to prove himself in action he accepted. Writing from underneath a lumber wagon, “with a borrowed pencil, using stolen paper and my very last envelope” he wrote:

I saw at once that the gunners were going to have all the fun in the firing line – our present position being too dangerous to land many horses. I grew rather afraid that I might get left rather in the background [as a driver] so I changed my opinion about drivers and gunners and the first opportunity I had to speak to the Major I begged him to let me be a gunner which he was done.

Letter from Douglas Barrett-Lennard to his mother, "Active Service", [Anzac], 13 May 1915

In July, the 8th Battery found itself in the Pimple, a salient in the Australian line just opposite the Turkish Lone Pine trenches in the central Anzac sector. From 13 July to 17 July, when the bombardments of Steele’s Post were most severe, the 8th Battery fought a daily duel with several Turkish 75mm artillery guns opposing them. On 17 July, Douglas wrote a letter to his father talking of the coming “big move” he and the battery were about to participate in and that: “I would like to be with you but still would not miss this show for anything.”

Later that day, a high explosive shell from one of the Turkish 75’s hit the shield of No. 1 gun, the gun that Douglas was manning, and blew away its crew. Charles Bean details the event:

Sergeant [Sydney Arnold Taylor], covered with wounds, struggled to continue firing, but the relieving detachment, which had sprung at once to the gun, forced him, strongly protesting, away from it. “See after the other,” he said, “I’m only scratched.” Of “the others” one gunner, Barrett-Lennard, a youngster of twenty-one, lay with an arm and a thigh shattered, but life lingered for a minute or two. “Look after the sergeant,” he insisted. “I’m all right – I’m done, but, by God, you see, I’m dying hard.” Another, Stanley Carter, part of whose back had been torn away, also regained a brief consciousness before he died. “Is the gun alright, sergeant?” were his first words. Of such mettle were the men who, under the most insuperable difficulties of Anzac, fought their guns throughout the campaign.

The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918: Volume II, The Story of Anzac: from 4 May, 1915 to the Evacuation

Men of 8th Battery, 3rd Australian Field Artillery Brigade, loading a shell into No 1 gun at Anzac. Note the ammunitiion boxes and extra shells in the background.

Letters from his friends and commanding officers to his parents detailed that, despite in great agony and slowly dying from his wounds, he demanded that those others wounded be treated before him. They also wrote of his bravery, courage and popularity with his fellow soldiers and commanding officers alike. Below are excerpts of letters sent to Douglas’ parents after his death:

…although he seemed to fully realise the seriousness of his own wounds, he asked that others be attended to first…that such bravery should come from a boy of 20 years of age and bearing in mind the painful nature of his injuries…

Copy of letter from [Lieutenant Percy Malcolm Edwards] to "G. C. 8th Battery", 18 July 1915

His death will be a great and distinct loss to the Battery as he proved himself an efficient and very gallant soldier and had he survived would certainly have received recognition of his many good qualities.

Letter from Major [Alfred Joseph] Bessell-Browne to the father of Douglas Barrett-Lennard, 20 July 1915

He bore his terrible sufferings with heroic courage and fortitude, was clear and conscious to the last and gave his final messages to those he loved so well, calmly and fearlessly he set an example for gallantry, self-sacrifice and fortitude which I cannot think can be surpassed and which will be handed down in his famous Battery for many a long year to come.

Letter from Colonel [Joseph John Talbot] Hobbs to the father of Douglas Barrett-Lennard, 22 July 1915

It has been a terrible blow to the battery as poor little Doug was a favourite with everyone and proved himself to be one of the bravest of the brave in the battery. It was his determination, pluck and originality that won such admiration from his comrades…His last words were “Tell them at home that I died bravely fighting on my gun. May God grant you all strength of your loving son and the best friend of his heart broken pal.

Letter from [Gunner Thomas Donald] Cusack to the father of Douglas Barrett-Lennard, 18 July 1915

The event also spoke more broadly of the character of the 8th Battery and the Western Australian men that formed it:

A wooden cross marks the grave of 1879 Driver (Dvr) Douglas Barrett-Lennard of Guilford, Western Australia, at Shell Green Cemetery at Gallipoli.

This is how the men of this battery die:- When the smoke from the bursting shell had cleared away, Wallis ran up to see the damage. He found Mick Taylor crawling about the ground, covered in blood and dazed. Bill said, ‘Are you badly hit, Mick?’ ‘No, Bill,’ he said ‘I am only scratched; look after Doug and Stan.’ (We subsequently found that he was wounded in 14 places.) Bill Wallis then picked up Doug Lennard. The poor lad had one arm off, one leg shattered at the thigh, and internal wounds. He said: ‘I’m done; look after Mick and Stan; don’t mind me.’…Carter was leaning on the gun. He had a fearful wound in the side. He said: ‘I’m sorry I’m moaning; I know it will upset the others, but I can’t help it.’ He died, poor lad, almost immediately. His last words were, ‘Did they get the gun?’ Doug was in fearful agony, but kept saying, ‘I’m dying, but, by God, I’ll die game.’ He lingered for two hours and it was a terribly pitiful thing to watch. His last words were, ‘I died at the gun, didn’t I?’ And so he went, dear lad, the most gallant, the most unselfish little soldier God ever made. He taught us all how to die…I do not think in the whole history of this war there is anything to eclipse this incident for gallantry of unselfish devotion to comrades. The General spoke to us all. He said ‘Dear lads, I have heard of nothing grander than the way your comrades died. I am proud of your battery. I only hope that when you return you will be appreciated as you should be. We buried the dear lads side by side at midnight. It was a real soldier’s burial. The minister’s voice was drowned in the crack of bullets whistling overhead. And thus we left them.

“How the men in this battery die: extract from a soldier’s letter,” The West Australian, Saturday 28 August 1915 [written by Corporal Hector Roy McLarty]

Douglas Barrett-Lennard, the young man from St. Leonard’s near Guildford, had been very cognisant of his youth, inexperience and even his lack of French and terrible dance skills. He was anxious to prove himself, and did so beyond measure on 17 July 1915. He is buried at Shell Green Cemetery at Gallipoli in Turkey.

Australians can be proud of the men of the 8th Australian Field Artillery Battery. The story of the battery did not end on 17 July 1915. It went on to serve on the Western Front in the years after Gallipoli. However, the events of that fateful day demonstrate a selflessness and courage under fire that became typical of the Australians that served during the First World War.

Douglas' letters have been digitised as part of the Anzac Connections digitisation project and can be viewed online here. The account of his service and his last days is immortalised in these letters. Accordingly, they are as precious to us here at the Australian War Memorial as they were to him and his family.