New in the Second World War Galleries

Twenty new and unique objects from the Research Centre’s collections have been placed on display in the Second World War Galleries. These original items include letters from prisoners of war, a flyer on the Anderson air raid shelter, a Changi concert program, ration tickets, propaganda leaflets, a camp newsletter made by German internees in Australia, membership cards for Italian fascist groups in Adelaide and Sydney, and instruments for the Japanese surrender.

These rare and original objects have replaced others that are due to be rested to ensure their long-term preservation, as exposure to light can cause fading over time.

Below are two highlights from the latest objects now on display.

Thomas Walsh on the bombing of Rabaul

Thomas Walsh describes the aerial attacks on Rabaul to “My Dear Mum”, PR05259

Thomas Walsh was a telephone technician with the Postmaster General’s Department in Rabaul, a coastal township on the island of New Britain in the Australian mandated territory of New Guinea, when Japan entered the Second World War and began its rapid southward advance. With New Britain coming under an increasing threat of attack, the 40-year-old Walsh joined the reservist New Guinea Volunteer Rifles and helped prepare Rabaul’s defences. In a letter to “My Dear Mum” in January 1942, Walsh remarked, “I am [well] thank God … we are building some rather swanky dug outs with all mod cons”.

Air raids on Rabaul had started on 4 January. “Enemy planes have paid us daily visits & some are twice daily girls”, Walsh wrote to his mother Catherine a couple of days later, “It’s a very eerie sight and feeling to see them approach at great heights.” As almost an afterthought, in an attempt to allay her fears, he added that “little damage has been done” and there are “no European casualties”. Catherine was likely already aware, however, that all Australian women and children had been evacuated from New Britain, and that the rail network in Rabaul had been bombed.

Walsh remained stoic and made light of the situation in a letter to his “Dear Mum” a week later. After a couple of days of relative quiet, he informed her that “the peace was broken at noon today when a flock of Japs came over, and dropped a few eggs”. The bombs caused “no damage and no casualties”, he was quick to add. Walsh ended the letter with “Prayers love and best wishes to all”. This letter, dated 16 January 1942, was the last Catherine received from her son.

Japanese forces invaded Rabaul on 23 January 1942. Within a fortnight, the Australian garrison on New Britain had fallen and all remaining soldiers and civilians (including Walsh) became prisoners of the Japanese. Four months later, Walsh embarked aboard the ship Montevideo Maru for transport to the Chinese island of Hainan. The ship was mistaken for a Japanese troop ship and sunk off the coast of Luzon on 1 July 1942 by the submarine USS Sturgeon. Walsh was one of 209 civilians, and 1,052 prisoners, who died when the ship sank. As the majority of the prisoners were Australian, the sinking of the Montevideo Maru remains the deadliest maritime disaster in Australia’s history.

Catherine Walsh did not receive formal confirmation of her son’s death until October 1945. Walsh’s penultimate letter, dated 9 January 1942, is on display with a partial nominal roll of the civilians embarked aboard Montevideo Maru compiled by investigators in 1945.

Letter from Millicent Addison to her prisoner-of-war son, Percy

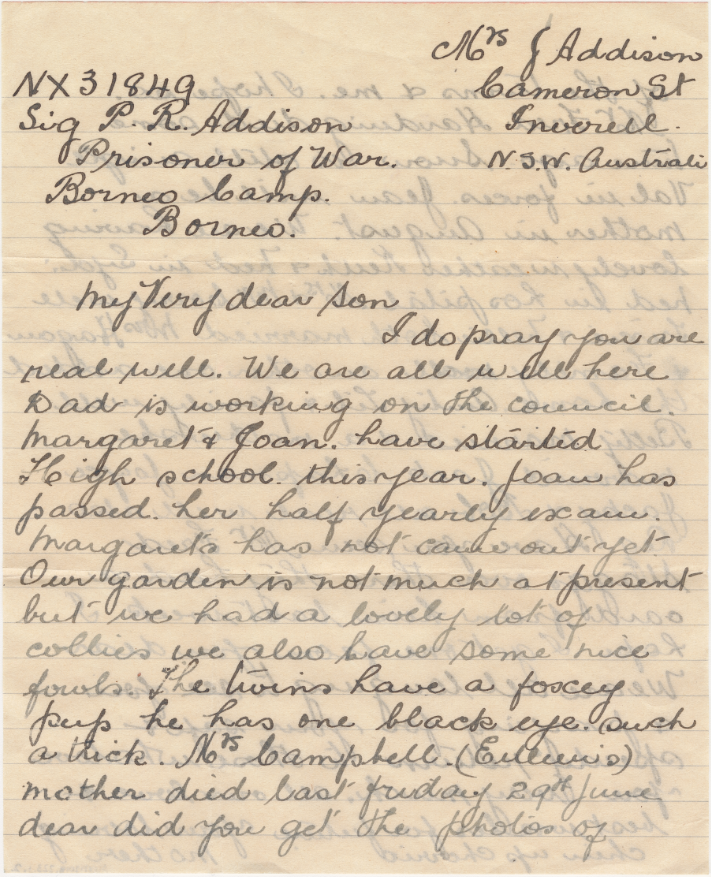

Millicent Addison’s letter to her “Very dear Son”, Percy, AWM2018.223.1.2

By July 1945, Millicent Addison had not seen her son, Percy, in four years. Writing to “My Very dear Son”, Millicent provided Percy with updates on all of the latest news from home. She asked, “Have you seen Mr Fred Staggs over there?” Staggs’s family, she informed Percy, “had a card from him last week. I hope I get one from you dear”, Millicent added almost pleadingly. “We are all longing to see you,” she continued, “& praying for your safe & speedy return to those who love you very much.” “Chin up”, she reminded him. Percy never received the letter.

Private Percy Addison had been a prisoner of war since February 1942. As part of the 2/30th Battalion, Addison embarked from Sydney in July 1941 for garrison duties in Malaya. The quiet, and often boredom, of the next four months was shattered when the Japanese invaded Malaya in December. Addison saw action around Gemas and Johore on the Malay Peninsula, before being evacuated sick. Shortly after, he became a prisoner of war with the fall of Singapore, alongside some 130,000 other British and Dominion soldiers.

In July 1942, Addison was transported to Borneo as part of B Force and imprisoned at the infamous Sandakan prisoner of war camp. The prisoners at Sandakan were used to build an airfield, which from 1944 came under increasing attack from Allied bombers. The Japanese ultimately decided to abandon Sandakan. In January 1945, in the first of three forced marches from the camp, Addison and 469 others departed Sandakan. With minimal food or provisions, the prisoners were marched through 260 kilometres of dense jungle to Ranau;157 did not survive the journey and many more died in the following weeks. Addison made it to Ranau, but collapsed and died from illness on 15 May – six weeks before Millicent wrote her letter. No one was able to inform Millicent of her son’s death until November 1945, almost three months after the war had ended. She had continued to write to Addison in the meantime, hopeful that he would return home.

Millicent’s letter is displayed in the Sandakan gallery, alongside photographs of Addison and the 1,786 other Australians who died as a result of the death marches.