'I'll never draw a line except to show war as the filthy business it is'

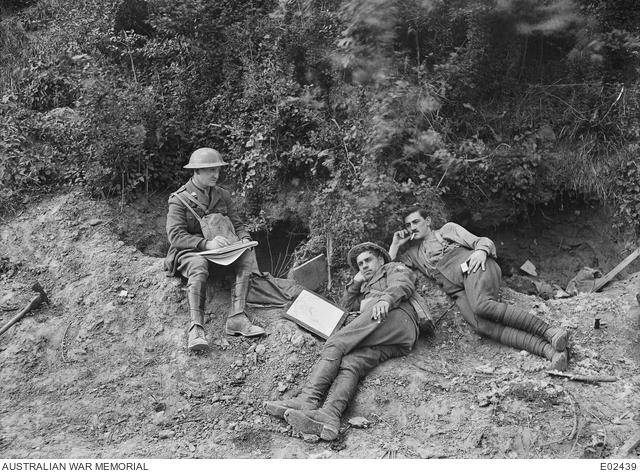

Lieutenant Will Dyson, left, sketching, in the 'Caterpiller', near Ville-sur Ancre, in France, in May 1918. German lines were less than 500 yards from this point, and ten days before, Australians of the 6th Infantry Brigade had cleared a number of German machine gun posts in stiff fighting.

When the First World War broke out, artist Will Dyson was determined to document it.

But he had no interest in portraying great battle scenes; he wanted to represent the experiences of the ordinary soldier — hardships, loneliness, exhaustion and miserable conditions.

He was wounded twice during the war and his brother-in-law was killed in the Second Battle of the Somme, yet he returned again and again to produce some of the most emotive drawings of his career.

More than 100 years later, his drawings of Australian soldiers on the Western Front are as powerful today as when they were created a century ago.

Going over the old ground with B..., Pozieres, charcoal, brush and ink, 1917. The work depicts three men standing in what had been the battlefield of Pozieres on the Western Front. The three men are, from right to left, a soldier in uniform with full kit, wearing a tin helmet, C.E.W. Bean, wearing a slouch hat and holding a pipe in his outstretched left arm, and an officer wearing a cap.

Australian War Memorial senior art curator Anthea Gunn has long been interested in Dyson’s story.

“He was already a well-known cartoonist in the press in Australia and London, and goes off to war determined to document what he’s seeing,” Gunn said.

“He was really focussed on the everyday soldier and he didn’t try to heroicise what he saw. For him, I think, the heroism was in the endurance, and in enduring these terrible conditions: the terrible food, the terrible weather, and the sheer sense of you didn’t know how this could possibly end, or when it could possibly end.

“It was the everyday soldier that he wanted to see recognised and understood so he was trying to capture this sense of what these men were going through to demonstrate what war is really like.

“He talks about how he was only going to draw something to show war as the ‘filthy business that it is’.”

Lieutenant Will Dyson sketching in the 'Caterpillar', near Ville-sur Ancre, in France in May 1918. The 'Big' and 'Little Caterpillars', so called from their worm-like appearance on the map, were sunken roads about 15 or 20 feet deep, outside the village, leading up to Morlancourt Spur and directly across the front of the 6th Infantry Brigade advance in the early morning of 19 May. Both Caterpillars were machine gun nests, and both were cleared by dashing attacks of the 22nd Battalion.

The ninth of 11 children, William Dyson was born in Ballarat, Victoria, in 1880. His talents for drawing and writing were encouraged and influenced by his elder brothers Ted and Ambrose, who were regular contributors to the Sydney Bulletin. His first cartoon was published in the Bulletin in 1897 and by the turn of the century he was a regular contributor to newspapers in Melbourne and Adelaide.

In September 1909, Dyson married Ruby Lindsay, sister of his close friend, renowned Australian artist and editorial cartoonist Norman Lindsay. Ruby was a talented and recognised artist in her own right, and the pair moved to London together to further their artistic careers.

Dyson's big chance came in 1912 when he was appointed cartoonist-in-chief at £5 a week to the new labour newspaper, the Daily Herald, whose editor gave him a full page and the freedom to express his ideas.

He was extremely critical of the Kaiser and German militarism, and when the First World War broke out in 1914 he was determined to document it.

Stretcher bearers near Butte de Warlencourt, charcoal, pencil and wash on paper, 1917. This work was reproduced in Australia at War: Drawings at the Front (London, 1918) with the following caption: 'They move with their stretchers like boats on a slowly tossing sea, rising and falling with the shell riven contours of what was yesterday no man's land, slipping, sliding, with heels worn raw by the downward suck of the Somme mud...'

“Despite having moved to Britain, Dyson remained fiercely patriotic,” Gunn said. “He saw that Australians were just being devastated through the war and he became committed to making sure their story was known.

“At around the same time he actually became eligible for British conscription, but he wanted to serve with the Australians so he put it to the Australian High Commissioner in London that he could forgo pay as long as he had access and was an honorary enlistment in the AIF.”

In 1916, Dyson wrote to AIF commander General Birdwood, stating his aim was to “interpret in a series of drawings, for national preservation, the sentiments and special Australian characteristics of our Army”.

Going up to the line near Vaux, crayon and pencil on paper, 1918. Depicts war damaged landscape near Vaux, the Somme, with a line of soldiers with full kit returning to the front line, in the summer of 1918.

He was granted a position as honorary lieutenant and in December 1916 travelled to the Western Front.

“By 1916 the true horror of the Western Front, and Australia’s role in it, was becoming apparent,” Gunn said.

“It is that real low point in the war, and conditions are just utterly terrible. It was all rain, snow and mud and he started drawing the everyday experience … soldiers giving each other haircuts, trudging through the mud … and he basically did that for the rest of the war.”

The mate (In memory of W..., Machine Gun Company, Messines Ridge), charcoal, brush and ink on paper, 1 August 1917. Depicts an Australian soldier carving a cross with an ornate rising sun for his fallen mate. Dyson witnessed this event on 1 August 1917 on Messines Ridge near Ypres in Belgium.

It was in France that Dyson met Australia’s official war correspondent Charles Bean.

“Dyson arrived in the little village of Montauban in the December of 1916, and he and Bean met almost immediately,” Gunn said.

“Bean had been advocating that art should be commissioned, but he was very much of a view that they should recruit artists from among the enlisted troops.

“He believed you had to be a soldier to really be able to depict the experience, but Dyson was able to show Bean that artists who weren’t soldiers could depict something of the truth of this experience as well which was essential.

“Bean can really appreciate that Dyson gets it, and within the week, Bean is writing in his diary that “Dyson is an able man at hisand he’s game.”.

“He felt Dyson really captured the essence of the soldiers' experience.”

Official War Correspondent, C.E.W. Bean, with John Masefield, Will Dyson, and Alexis Aladin, going over the old battlefield at Pozieres.

Lieutenant Will Dyson sketching a horse in April 1918.

Lieutenant Will Dyson, left, with an assortment of war relics in April 1918. They were collected for the Australian War Museum by the 13th Infantry Battalion, the Commanding Officer of which, Lieutenant Colonel D. G. Marks DSO MC, appears on the right. Standing in the doorway is Private L. Brown MM.

In May 1917, Dyson was formally appointed as the first official war artist attached to the AIF as part of the Official War Art Scheme.

Unlike his earlier, satirical cartoons that exaggerated and mocked the physical characteristics of his subjects, Dyson’s war art used pose and gesture as powerful expressions of a soldier's experience.

“During the war, his work was probably the best known of Australia’s official war artists,” Gunn said.

“There were artists who had been commissioned from among the enlisted troops to serve with the official war records section, but the other official war artists, like George Lambert and Arthur Streeton, were Australians artists who were resident in London.

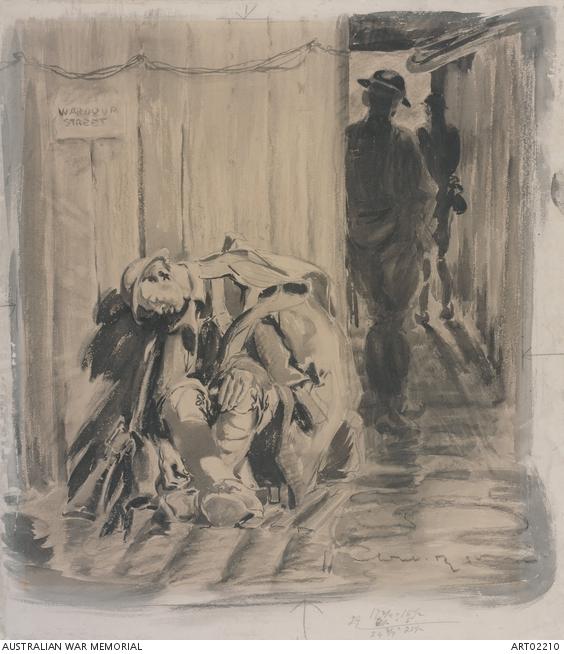

Dead beat, the tunnel, Hill 60, brush and ink, charcoal on paper, 1917. Depicts an exhausted Australian soldier wearing full kit and greatcoat, sleeping in a tunnel during the Third Battle of Ypres. Dyson had no illusions about war. He declared: 'I never drew a single line except to show war as the filthy business that it was.'

“They would be commissioned to go for three months at a time, and then they would come back and their sketches would go to the government for a flat fee per day, but Dyson had quite a different arrangement, and he was basically full time for two years.

“He was the only one to have that kind of access, and I would argue the only one who probably wanted that kind of access …

“There is this sense of compulsion in Dyson’s work … and he did the same thing again and again; just drawing these soldiers and trying to capture the breadth of their experience.

The amateur (`Who's cutting this hair, you or me?'), oil on cardboard, 1920. Depicts two Australian soldiers outside their billet in France, one cutting the other's hair in a rough and awkward manner.

“By the end of the war he’d only been paid about 180 pounds, so he was virtually left penniless, and his wife bore the brunt of that.

“She was at home in London with their young daughter, Betty, and was pretty much at her wits end. She was terrified that she would be widowed or that Dyson would be incapacitated.

“She knew that he had been wounded and that death could come easily, so although they had some savings at the start of the war, she pretty much didn’t touch that money, and she lived on nothing, to the point of not eating at times.

“They had both sacrificed a lot, but he created this incredible body of work, and there are now hundreds of his drawings and lithographs in the Memorial collection.”

Coming out on the Somme, charcoal, pencil, brush and wash on paper, December 1916. This work is from Dyson's early battlefield observations. It shows exhausted Australian troops, draped in waterproof sheets, plodding through the rain and mud as they reach Montauban, a ruined village now containing temporary army huts and supply dumps several kilometres behind the frontline. Desperately weary, they are stooped, wet and miserable. Their journey has been across ground fought over for the past six months and now consisting of nothing but mud and desolation.

His work and ideas would have a profound influence on Bean and the foundation of the Memorial itself.

“Dyson was part of this circle around Bean,” Gunn said.

“Bean was renowned for the fact that he didn’t just sit in the hotel waiting for news to be brought back from the front line; he actually went as far forwards as he could, so he and Bean would be watching these battles unfold

“They were right in amongst it, and it’s a miracle that neither of them was killed, but he was seeing those crucial events unfold, and he would often be with Bean again when they went and interviewed people in the immediate aftermath.

“They were coming up with the idea for the Australian War Memorial at the time and in his letters, Bean talks about how Dyson was a really integral part in that, particularly in relation to things like the dioramas in the First World War galleries.

With the 2nd Australian tunnellers near Nieuport, lithograph on paper, 1918. Depicts members of the 1st Australian Imperial Force, 2nd Australian Tunnelling Company with two men in the tunnel.

“They were coming up with these ideas to try and convey the scale of this war to people back at home in Australia, and these dioramas wouldn’t just be models, they would be actual artworks that would show the whole history of the war.

“They have remained absolutely essential to the First World War galleries right from the opening of the Memorial to the present day, and I often talk to people who have these incredibly vivid memories of when they first saw the dioramas as children so it’s not only Dyson’s work, but his whole contribution to the Memorial that is his lasting significance.”

Dyson returned to his work at the Herald after the war, but was left grief-stricken when his wife Ruby died on 20 March 1919, a victim of the Spanish flu.

The influenza pandemic swept the globe after the war and Ruby died in his arms just a few days before her 34th birthday.

Woman praying at a Shrine, pen and ink, pencil, charcoal, white gouache on paper, c1916. Depicts a young French woman kneeling before a shrine with her head upturned and praying. At the top of the shrine is a small crucifix, a common sight in France during the First World War. Behind her are other women, carrying bundles and babies and running or being rounded up and moved away by a number of German soldiers. The work relates to the German policy in April 1916 of deporting men and women from German-occupied Lille in France to other districts to provide forced labour during the First World War.

“They were deeply in love and they were quite excited about the future,” Gunn said.

“They were going to get out of London, go into the country, and allow Ruby time to focus on her career, but Ruby goes off to visit the Lindsay family in Ireland with one of her brothers.

“She comes back to London with these symptoms of a cold and within a week she’s dead.

“Dyson writes to his brother about getting nurses and doctors in and desperately trying to help her, but he loses her just a few days later.

“He is just utterly devastated and I don’t think he ever really truly recovered.

“He was just facing the worst kinds of grief and when he writes to his brother he talks about how he doesn’t quite know where time has gone.

“He’s in this absolutely black mood, and although he does remarry later on, there is something missing in his spark, and he never quite gets back to where he was pre-war.

Wine of Victory (Wounded German prisoners near Ypres), lithograph on paper, 1918. Depicts a wounded German soldier, captured near Ypres, being led by Australian soldiers across a war damaged landscape. Rows of other soldiers can be seen in the background.

“After all that he had witnessed during the war, it was like Ruby’s death was the final straw, and he was never quite the same after that.

“It was just brutal, and there must have been so many families with similar stories. People who had survived the war were just looking forward to getting back to whatever normality was, and adjusting to it, and then for this virus to come along and take so many more lives, and seemingly even more indiscriminately than the war, must have exacted untold trauma ...

“He was depicting history as it happened, but of course he never knew what the ending was going to be …

“He captured the sense of the weariness of the soldiers, the trudging back from the front lines, one foot in front of the other, and the sheer utter exhaustion on these men’s faces, and it is incredibly affecting.

Eternal waiting, charcoal, pencil and wash on paper, 1917. Depicts three soldiers, two sitting on ground, all wearing great coats and waterproof capes and carrying full kit. This drawing was originally intended by Dyson as a battalion Christmas card. He wrote that it was 'representing some of the boys thinking of Australian summer, in the mud of this Flanders winter, but the thing was a little too funereal to force on fighting men. I did them one dwelling more on the light and gamesome aspects of a life of slush, sandbags, shells and sacrifice.'

“Bean had always intended that there would be a dedicated room of Dyson drawings at the Memorial and that it would be a permanent feature, but of course the Memorial building, which was originally built for the First World War, has come to accommodate the entire military history of Australia, so that dream has long since departed.”

Dyson died in London on 21 January 1938. His death made newspaper headlines around the world and his last cartoon was published on the day he died. He had drawn two vultures perched on a crag watching Franco’s planes bombing Barcelona. His caption read: “Once we were the most loathsome things that flew!”

The Memorial is temporarily closed to the public, but the Memorial is still telling stories about the Australian experience of war. To learn more, visit here.

The Memorial’s online exhibition Art of Nation is a digital interpretation of Bean’s original proposal for the national memorial, including his Dyson Gallery.