'I saw the look of shock in their eyes'

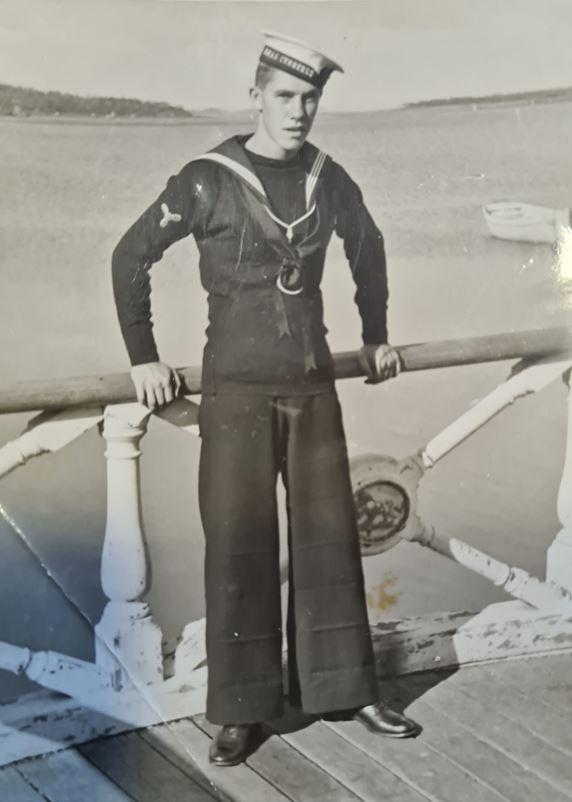

Percival Pascoe was killed when HMAS Sydney was sunk by the German merchant raider Kormoran in November 1941. Photo: Courtesy Baden Pascoe

Baden Pascoe was with his parents when the news came.

It was in the middle of the Second World War, and his older brother Percival was serving as a stoker aboard the light cruiser HMAS Sydney.

The pride of the Royal Australian Navy, Sydney had been lost off the West Australian coast after an attack by the German merchant raider Kormoran in November 1941.

“I remember the moment we received the telegram advising that he was ‘missing in action,’” Baden said.

“We were apprehensive, as all were in those days, especially if [the telegram] arrived early in the evening.

“There must have been something about it – I can't remember why now – but my mother and father were sitting out back in the garden, together with me, at about sunset, just after the evening meal, when the telegram arrived.

“I saw the look of shock in their eyes when they read it.

“It gets me now, just talking about it ...

“Then they explained it to me, but I didn't really process it very well at my age.

“It didn't really hit me hard until I grew older and I learned a bit more about it.

“All those things were kept quiet by your parents in those day. They just didn't say a word.

“You could tell something was wrong, but you didn't know what. And then they explained what had happened. And that was it.

“I was only 10 years old and he was about 11 or 12 years older than me.

“I knew he was in the Navy, and he was on the Sydney, and of course, when we got the telegram, that's when I started to realise what was going on.

“But, at 10 or 11, it didn't really sink in.

“From that point, they just sat in silence for some time.

“But I don't know how I reacted.

“I hardly knew him.

“He’d gone away before I could even really remember.”

Percival Pascoe. Photo: Courtesy Baden Pascoe

Baden’s brother Percival was born in Boulder, Western Australia, on 28 November 1919, the third of four children born to Amy and Leslie Pascoe.

He was working as a shop assistant when he enlisted in the Navy at Fremantle on 3 February 1939 for a period of 12 years.

He joined the crew of Sydney in June and, in February 1940, was promoted to the rank of Stoker.

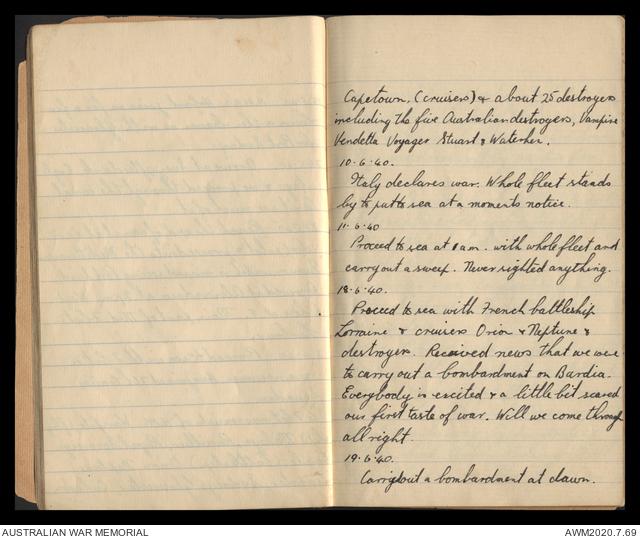

He kept a diary from April 1940 to February 1941, covering the ship's departure from Australian waters, its service on convoy escort duties in the Indian Ocean, its operations with the 7th Cruiser Squadron in the Mediterranean, and its eventual return to Western Australia.

“At sea with convoy,” he wrote. “Australian coast has long since disappeared.

“A bomber of the RAAF is circling the ships on the lookout for submarines...

“Singapore is sighted on the horizon...

“Everything is strange as we proceed up the harbour.”

In his diary, he recounts sailing through the sea mines at Singapore, of sightseeing in Colombo, and of steaming up the Suez Canal.

In the Mediterranean, he writes of coming under aerial attack and of the nerve-racking nature of persistent air raids. He also records Sydney’s service on anti-submarine operations as well as contraband patrols, sweeps and escort duties, and discusses tensions with the French fleet in Alexandria following the fall of France to Germany in June 1940.

He recounts the squadron's work on convoy operations, Sydney's involvement in the shore bombardments of Bardia, Scarpanto and Valona, and the naval battles of Espero Convoy, Calabria, Cape Spada, and Cape Passero.

“Received news that we are to carry out a bombardment on Bardia,” he wrote. “Everybody is excited and a little bit scared. Our first taste of war. Will we come through all right?”

Percival Pascoe recorded his thoughts and feelings in his leather-bound diary.

Sydney went on to build an impressive record of war service and was celebrated for her successful battles in the Mediterranean. Percival recorded his thoughts and feelings about it all in his leather-bound diary.

“The Italian fleet is at sea and we are hoping to meet them,” Percival wrote in July 1940.

“Next day, over came the bombers, dozens of them. They came over six times in the morning and seventeen times in the afternoon, twenty three attacks in one day is not bad going and believe me we’re glad it’s over.”

The following day, Percival noted: “More bombers today, nearly as bad as yesterday. We are out of [high-explosive] shells now, so we’re firing practice ammunition. These explode just like an ordinary shell, but are harmless. They just make a puff of white smoke.”

He was grateful when Sydney arrived in Alexandria two days later. “No air raids today, which was a great relief,” he wrote. “We can’t stand much more of that. Everybody’s nerves are nearly gone. We jump at the slightest stand.”

Having demonstrated her fighting prowess in the Mediterranean, where she famously sank the Italian cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni, Sydney and her crew received a hero’s welcome when they finally returned to Australia in February 1941.

Baden Pascoe wearing his brother's HMAS Sydney hat. Photo: Courtesy Baden Pascoe

Baden remembers seeing his older brother on leave for his 21st birthday and proudly wearing his sailor’s cap. It would be the last time they were together.

The cruiser began operating off the Western Australian coast in late September 1941, escorting convoys from Fremantle to the Sunda Strait in the Netherlands East Indies. From there, they would join other Allied warships to continue their journey to Singapore.

Sydney was steaming back to Fremantle on the afternoon of 19 November when the crew spotted a suspicious merchant ship, disguised as the Dutch steamer Straat Malakka. It was, in fact, the heavily armed German merchant raider Kormoran, which had already sunk ten unsuspecting merchant ships in the Indian Ocean and taken another as a prize.

Sydney had almost drawn alongside the mysterious vessel when it hoisted its German naval ensign and opened fire with guns and torpedoes.

In the battle that followed, both ships were mortally damaged.

As the German sailors abandoned their stricken vessel, they watched the Australian cruiser, now only a distant glow on the horizon, disappear into the night.

Torpedoed and ablaze, Sydney sank in the early hours of 20 November 1941, just days before Percy’s 22nd birthday. The entire ship’s complement of 645 was lost.

Today, Percy’s name is among those listed on the Plymouth Naval Memorial in Britain, the HMAS Sydney II Memorial in Geraldton, and the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Baden visited the Memorial to place a poppy by his brother’s name on the Roll of Honour.

His parents never spoke about their loss.

“No, not in front of me,” Baden said.

“Of course, it was still in the middle of the war.

“[My siblings] didn't even talk about their own selves, and yet they were both in the war. My eldest brother, Ronald, was in New Guinea, and I didn’t know.

“I didn’t even know he’d left Australia ... I had inklings of things happening, but I had no idea what was really going on.

“He had been on guard duty at Fremantle when the prisoners from the Kormoran arrived [after the sinking of the Sydney] and he had to guard them... He only told his daughters about that after the war, but he never spoke to me about that at all.

“He went into the railways and my sister, Gweneth, was a teacher. She came back during the war to work in the munitions factory that they had in Kalgoorlie.

“But we didn't talk about the war for some reason...

“I found out later that my mother sent a cake to Percy, presumably for his birthday, but she never knew whether he received it. Apparently she always thought he was coming home. But she never spoke to me about it, probably because I was so young.

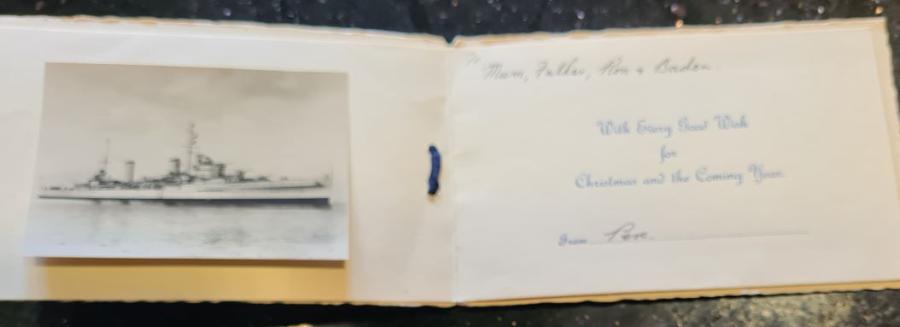

Percival sent this card home to his family in Boulder. He sent a separate one to his sister. Photo: Courtesy Baden Pascoe

"Everyone just kept it quiet, and of course, no one ever spoke about what they did in the war anyway.

“We just never talked about our brother much at all, except that he was our brother and that he’d died on the Sydney, nothing more.

“But then we had this diary that he wrote.

“I didn't even know it existed until my sister died and all of those things came to me.”

Today, Percival’s diary is part of the National Collection at the Memorial. It was donated to the Memorial in 2008 on behalf of his surviving siblings.

“Now when I talk about it, I do get emotional,” Baden said.

“It was fascinating [reading his diary for the first time]. I just couldn’t believe it.

“I’d like people to have the opportunity to read it ... to learn what happens when you're on a ship and what it was like during the war.

“I think it’s the best place for it.”

A note on the inside cover, says simply: “Dearly loved and ever remembered.”