“I was a prisoner in North Korea”

Press photographer Eric Donnelly was only 22 years old when he signed up for K Force in 1952, having seen a government advertisement in the Courier Mail calling for volunteers to fight in the Korean War. Shortly after enlistment, he undertook army training in the Blue Mountains, where he met his sweetheart, Desma Doreen McEvoy. On his final leave at Katoomba, Donnelly bid farewell to Desma, before travelling to South Korea to join the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR). Private Donnelly, a young and inexperienced soldier, was eager to test his mettle on the battlefield. That opportunity came on 14 January 1953, and on that day he was taken prisoner by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Private Eric Donnelly’s company was occupying an area known as Hill 355 or “Little Gibraltar”, close to the 38th parallel, when they received reports of enemy activity at Hill 227. Relying on old aerial photographs, the men set out on a reconnaissance mission led by Lieutenant Brian Bousfield. They reached their objective, stopping 200 yards from enemy trenches, and were ambushed. Unbeknown to the Australians, the PLA had built a new trench line further down the slope. Heavy fighting ensued, and all but three of the 18 men taking part in the patrol were wounded in the initial attack.

Private Donnelly was at the front of the patrol and closest to the new trench line, watching as a barrage of grenades flew over his head. Trying to identify the enemy’s position, made difficult by low visibility, Donnelly threw two grenades. The second reached its intended target and loud cries were heard from the Chinese trenches. As Lieutenant Bousfield shouted the order for the men to retreat down the hill, Donnelly made the four-yard dash to Private Peter White, the patrol’s badly wounded Bren gunner.

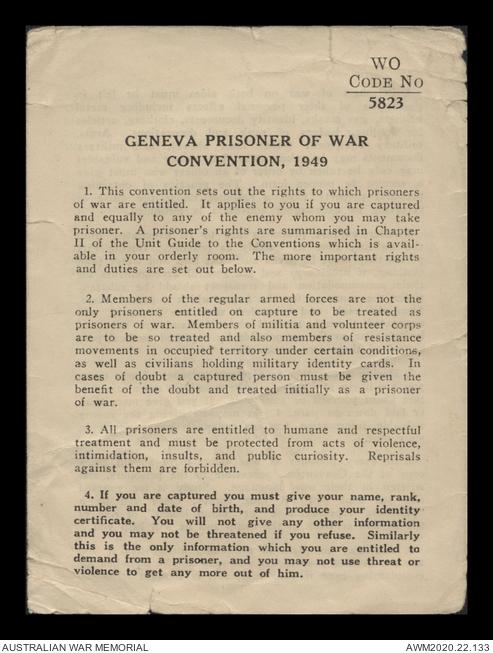

Geneva Prisoner of War Convention, 1949

Donnelly reached Private White, hoping to drag his body down the slope, when he was shot in the leg. Paralyzed from the waist down, Donnelly lay motionless in the snow next to White’s lifeless body before he was spotted by a Chinese soldier who grabbed him by the hair and dragged him into the trenches. In the months that followed, Donnelly did not receive adequate medical treatment for his leg wound. Suffering excruciating pain, he wondered if he would live to see Desma again.

Around midday, Donnelly was taken on a stretcher to a large tunnel underneath Hill 227. A Chinese officer approached the stretcher and asked him, in English, who he was. Private Donnelly gave the officer his identity card, and the officer then asked him a series of questions, telling him that if he did not answer truthfully, it would be difficult for him to get medical treatment. He was later moved to another location, travelling several days through mountainous terrain to an interrogation centre, and then a makeshift hospital that looked like a village hut.

Here a surgeon operated on his leg, removing bits of his shattered femur bone. Nurses applied a plaster cast to his leg, hip, and chest; he couldn’t sit up and would spend the next three months of his internment on his back. As the anaesthetic wore off and the pain in his leg intensified, it was his twenty-third birthday; his spirits were low.

Donnelly’s treatment as a prisoner of war was far from ideal. The Geneva Convention for prisoners of war stipulates that “all prisoners [are] entitled to humane and respectful treatment”. This was not always the case for the Australians interned in North Korea. Yet, there were moments during Donnelly’s internment when human solidarity triumphed. In an article for a regimental magazine, Donnelly recalled the following:

In the early hours of the following morning, when the pain was at its worst, a Chinese soldier came over and sat beside me. He looked at me for a little while and watched as I tried to control the pain I was experiencing and then he reached down and cradled my head in his arms. He began to sing in perfect English, the old Paul Robeson spiritual, “Swing Low Sweet Chariot, coming for to carry me home”. This is one of the most moving experiences that I will always remember.

News of possible release came several months later when Doctor Whong, a fluent English speaker who was sympathetic to the allied serviceman, came into the prisoners’ hut one morning to tell them that they might soon be freed. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army had agreed to negotiate an exchange of sick and wounded prisoners at Panmunjom. Private Donnelly was one of five Australian that were released on 23 April 1953 as part of Operation Little Switch.

Eric Donnelly spent three months as a prisoner of war, but the memories of his time in captivity remained with him for the rest of his life. Shortly after repatriation, Donnelly appeared on the ABC radio program Guest of Honour and recounted the events that led to his capture and his subsequent treatment. Donnelly continued to share his story in the decades that followed, publishing an article in Duty First in November 1991. The transcripts from that interview, as well as the article, are digitised and may be viewed on the Memorial’s website.

Wallet 1 of 1 - Papers relating to the service of Eric “Blue” Donnelly, 1953; 1991