Remembering the Mara brothers

Private Clarence John Mara. Credit: State Library of South Australia

On the 17th of April 1917, Sarah Mara received a cable at her home in Jamestown, South Australia. It relayed the news that her son, Sergeant Robert Mara, had died of pneumonia at the 36th Casualty Clearing station in December 1916. Five of the Mara brothers enlisted to serve in the Australian Imperial Force. At the time their mother received this cable, three of her sons were dead. She did not know what had happened to her two other sons, who had been missing since August 1916.

The Mara brothers came from the small community of Jamestown, in South Australia. At the turn of the century, the town had a population of less than a thousand people and most residents of Jamestown were employed in farming and pastoral work on sheep stations and wheat farms. There were 12 children in the Mara family, six of whom were boys. In their small rural community, the family was well known. Their eldest son, Alfred Mara, served in the South African War. At the conclusion of the war, he wrote to say he was leaving for Canada, and was never heard from again. This left the Mara family with just five sons, all of whom enlisted to serve in the Great War. The war was indeed a global conflict on a large scale, and the Mara brothers were just five men among millions who served their countries. Their story is interesting however, in that it showcases the breadth of experiences of those who served, and shows how a global conflict at its core, is the story of people. Their story shows how the Great War would have further reaching consequences than peace treaties and land movement. It would have consequences for the families, individuals and communities who felt the impact of the war on a far more personal level.

Sergeant Robert Spencer Mara. Credit: Virtual War Memorial

Robert Mara was the first of the brothers to volunteer, joining in August 1914. He was assigned to the 3rd Battalion. Walter Mara enlisted a month later and was assigned to the 12th Battalion. Robert and Walter had already arrived in Egypt when their younger brother Clarence enlisted in March 1915, followed shortly after by his twin brother, John, who enlisted in April. The twins not only shared their date of birth, they also shared their names; both born on the 22nd of December 1896 and named John Clarence, and Clarence John respectively. Both allocated to the 10th Battalion, the similarity of their names would later cause much confusion and anxiety. The remaining Mara brother, Ernest, enlisted in August 1915. He joined his brothers in the 10th Battalion which was predominantly composed of South Australian recruits.

On the 12th of December 1915, a letter from Robert Mara, who had served on the Gallipoli Peninsula, was published in the Barrier Miner, a newspaper from the remote mining town of Broken Hill. The headline read: “The brothers Mara: Five fighting at the front, four to avenge one brother’s death.” Private Walter Mara, having survived the landing at Gallipoli in April that year, had taken his own life whilst serving in the front lines of the Peninsula. In the days leading up to his death, his comrades noted he appeared depressed and often refused to eat his meals. On 9 June 1915 they heard a gunshot from his dugout and ran to help. There, they saw Walter Mara slumped over in his dugout with a rifle beside him and a handful of letters and postcards in his lap.

Robert’s letter, written to his mother read:

“I know it is hard for you, dear, all your sons leaving you, but still mother, you ought to be glad that you can send three more sons to help me avenge Walter’s death. You still have four of us alive and some poor mothers have lost their only son. Look on the bright side of this mother and think what a noble part you have played in the war. You have done what many a woman would be proud to have done, that is to send five boys to fight for their King and country… I feel sure that God will spare some of us to come back to you; and just think what a grand meeting it will be to come back after the war is over. You I’m sure will feel quite proud of the noble part you have played. Trusting God will bring me back safely to you.”

Private Walter Henry Mara. Credit: Virtual War Memorial

By 1916, the Gallipoli campaign had been abandoned. The four remaining brothers, Robert, Clarence, John and Ernest, were all sent to the Western Front. Robert, who had been promoted to the rank of Sergeant on the voyage to France, was immediately hospitalised upon his arrival, owing to illness. His hospitalisation spared him the experience that his three younger brothers would share in their first major battle near the French village of Pozieres in July 1916, where Australian units would take over 23,000 casualties.

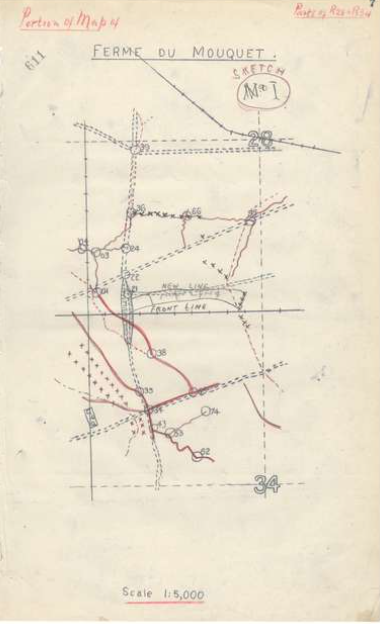

In August 1916, the former site of Mouquet Farm became the next objective for the allies, and the men of the 10th Battalion. Though the farm itself had been reduced to rubble, the cellars which remained had been incorporated into the German defences, operating as an ideal machine gun position. Owing to its location on the high ground overlooking Pozieres, its capture was essential to extend British control over the ridge. Unlike Pozieres however, attempts to capture Mouquet Farm ultimately failed. It was here, on the night of the 21st of August 1916 that members of the 10th battalion were sent over the parapet, though they were only running at half strength.

Map of the 10th Battalion’s attack at Mouquet Farm in August 1916. It was here that John Mara was killed in action and his brothers Clarence and Ernest were taken prisoner. Credit: NAA service record, Private C J Mara

Men who were later captured there described where the attack went wrong: “Our objective was the second line of enemy trenches. We encountered heavy machine gun and shrapnel fire and suffered heavy losses. We took the first line but were repulsed before reaching the second line trench owing to barbed wire entanglements. The sergeant ordered us to retire to the first line which we found had again been counter attacked by the enemy and reoccupied. We then took up our position in the second trench and held on till 8am in the morning when we ran short of ammunition and our small party was captured.”

It was during this attack that that John and Ernest Mara went missing, and Clarence was declared to have been killed in action. By this stage of the war, their family in Jamestown had one son in hospital, two sons who were dead and two more sons who had quite possibly shared that fate.

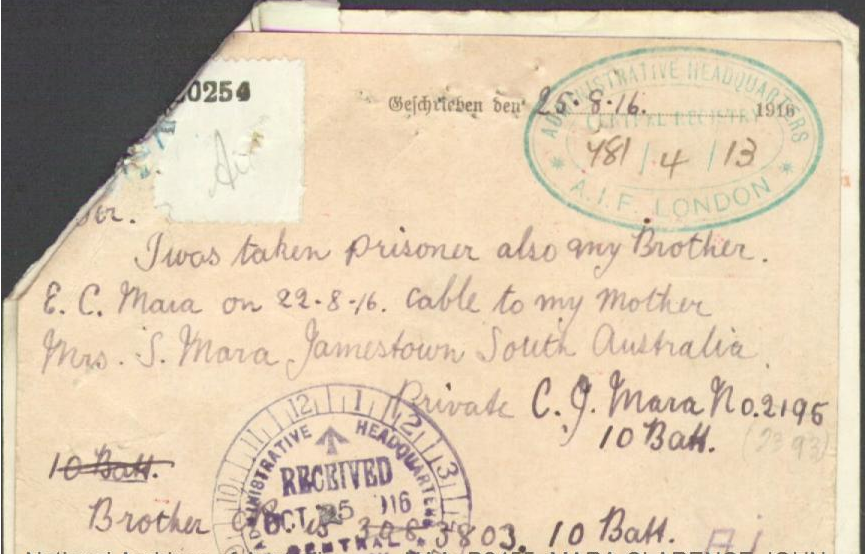

By 1917, the number of dead sons in the Mara family had risen to three, when Robert Mara died of Pneumonia. They still did not know what had happened to John and Ernest. It was not until April that year that the Mara family received a telegram stating that Clarence and Ernest were prisoners of war in Germany. The two brothers were among those who were captured on the morning of the 22nd of August when their company was surrounded and forced to surrender. Three days after their capture, Clarence sent a letter to the Australian Headquarters in London which read: “I was taken prisoner also my brother E.C Mara on 22.8.16. Cable to my mother Mrs S Mara, Jamestown, South Australia.” As this news took so long to reach her, she had endured months of uncertainty about the fates of her sons.

Postcard sent by Clarence John Mara advising that he and his brother were both prisoners of war. Credit: NAA service record, Private C J Mara

With the discovery that Clarence and Ernest were prisoners of war, it became clear that it was in fact Private John Mara who had been killed in action. Owing to confusion between the names of the twins, news of their fate had been incorrectly passed on to their next of kin. Clarence Mara, who was previously believed to be dead, was in fact alive and well. John Mara, who was previously missing, was now confirmed to have been killed in action, aged 20. His body was never located.

Private Clarence John Mara pictured in a German POW camp in Munster. Front row, second from the right.

Ernest and Clarence were initially sent to a prisoner of war camp at Dulmen, north-east of Cologne. They were eventually separated when Clarence was sent to work in a coal mine in Bochum where he worked underground for six months. Clarence was later sent to another coal mine near Dortmund and tried to escape, but was recaptured. He later said of his escape attempt: “I was recaptured and flogged by a German sentry and corporal for about five miles and when put under arrest was flogged again by the sentry in the presence of the under officer.”

Ernest was sent near Hammerstein where he was engaged in quarrying and was also subject to cruel treatment by his captors. In recalling his experiences, Ernest Mara said: “The treatment meted out to us was harsh. The food was bad. The medical treatment was fairly good. We had to work long hours and in all kinds of weather.

The brothers remained prisoners of war until the Armistice was signed in November 1918, at which point they were repatriated to England. In 1919, those who had survived the Great War began arriving back in Australia. When Ernest and Clarence disembarked at Adelaide, they returned to a family home far emptier than it had been in 1914.

Private Ernest Clifton Mara pictured with other prisoners of war in Germany. Back row, far left with the X above.

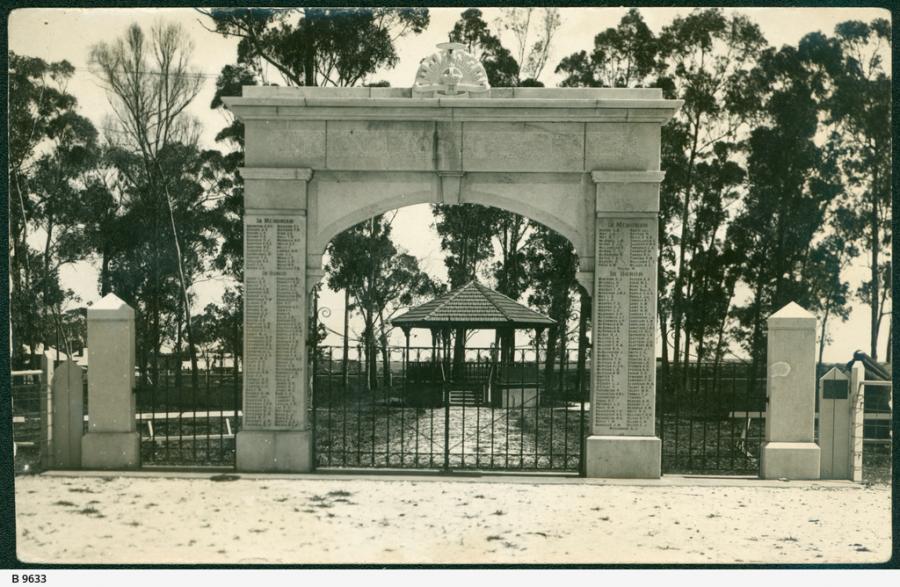

Jamestown War Memorial pictured in 1927. It bears the names of the five Mara brothers who served in the First World War. Credit: State Library of South Australia

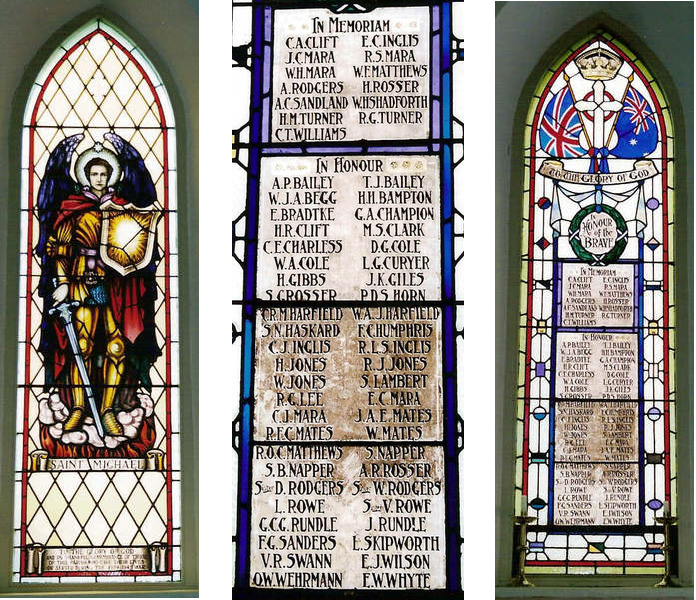

Located a two and a half hour drive from Adelaide, South Australia, is the small village of Jamestown. There, as in many places across both Australia and England, is a local war Memorial. It lists the names of the local boys who ‘answered the call’ for King and country. On this memorial, the name ‘Mara’ appears five times among the men of Jamestown who served in the First World War. Their name is repeated a further five times on a stained glass window in the local Anglican Church. The name Mara, listed over and over again, stands out on the Jamestown roll of honour.

Stained glass windows in the Jamestown Anglican church commemorating the service of the Mara brothers. Credit: Virtual War Memorial

Of the more than 400,000 Australians who enlisted to serve in the First World War, just five of them were Mara boys. Of the more than 60,000 who never made it home, just three of them were Mara boys. Of the five sons the Mara family had to give, all five of them enlisted. Their contribution was one hundred percent. One took his own life, one died of illness, one was killed in action and two became prisoners of war.

Jamestown War Memorial. Credit: Henry Moulds, Places of Pride

When comparing these numbers, the contribution of the Mara family to the overall war effort could appear inconsequential. But the consequences for their family and their community were far greater. Their story is unique in many ways, but is also replicated over and over again in thousands of other families and communities who bore the cost of war. When loss is replicated in the thousands, as it was in the First World War, the absence of a few men from each community is actually far more significant than it would first appear. The loss of men like the Mara brothers from their homes and communities left huge gaps in Australian society. Families were left without breadwinners, family businesses often suffered; grief was amplified by the distance and circumstances of war and whole communities found themselves missing men who had once been part of their everyday lives. Nothing was the same for Australian society in the aftermath of the First World War. Though the loss of a few men from each town mattered little in the operational sphere of war, that loss had huge repercussions for their families and local communities.