Rothberg the Spy: Rumours in the 24th Battalion, 1916

On the night of 29/30 June 1916, 2456 Private Albert Roth, 24th Battalion AIF went missing while taking part in a trench raid near Armentieres. This was one of a series of raids Australians undertook in late June /early July 1916, before the AIF fought at Fromelles and Pozieres. His mysterious disappearance led to a rumour spreading through the battalion - that he was a German spy!

Cloth patch for the 24th Battalion - all participants in the raid removed their cloth patches, identity discs and any other identification before taking part.

The Raid

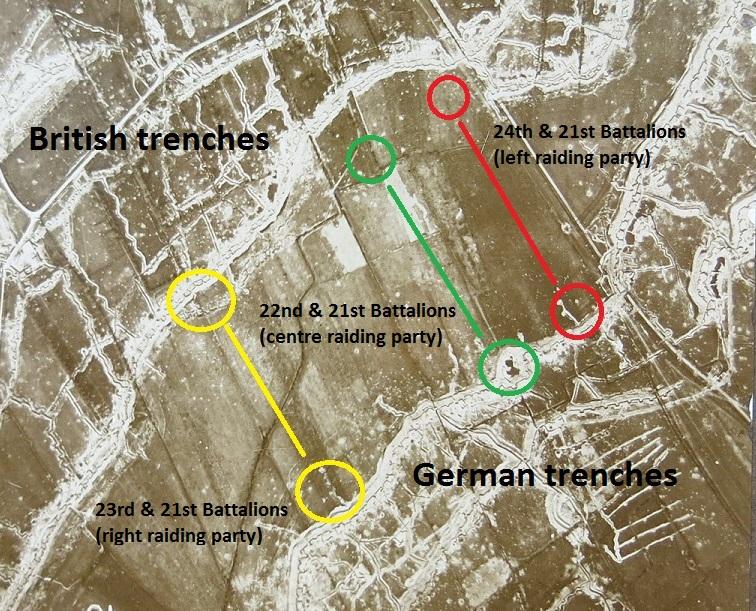

The raid was conducted by the 6th Brigade AIF (21st, 22nd, 23rd and 24th Battalions) who were divided into 3 sections – right, centre and left. The 24th Battalion made up the left raiding party under the command of Lieutenant James Carvick, with a covering party of men from the 21st Battalion. The scouts for the raid were under Lieutenant Alan Kerr. After two week's training, they left their billets on 29 June to rendezvous in a support line. They were dressed in old clothes and all identifying marks (such as colour patches and identity discs) were removed. Each man was given a numbered “raiding ticket”, they blackened their faces and hands and wore a white band on their arms to aid in identifying them in the trenches (the bands were covered with dark socks to hide them until they reached the German trenches). They were armed with revolvers or rifles with bayonets, and bombs and trench clubs.

Trench raiding club, similar to those issued to the 24th Battalion in 1916.

Their objective was the enemy trenches about 300 metres away, where they were to kill and capture as many Germans as possible and recover any documentation for intelligence purposes. It was mostly quiet while they made their way across no man's land, with only the occasional machine gun fire, but they had to stop and lie still on occasion when the Germans sent up flares that lit the sky and made it look like daylight. A few minutes before the attack, the British artillery bombarded the German trenches.

A ditch full of water and barbed wire delayed the left raiding party's advance but when they finally reached the trenches they briefly fell back when someone mistakenly gave the signal to retire (the word “bunk”). Realising the mistake, the party rallied and re-entered the German trenches, bombing dug outs and killing between 20 and 50 Germans (accounts vary) and capturing another six (although one escaped). When the 24th Battalion raiders withdrew from the German trenches, they took their dead and wounded with them while being covered by members of the 21st Battalion. Each man’s “ticket” was marked off when they returned.

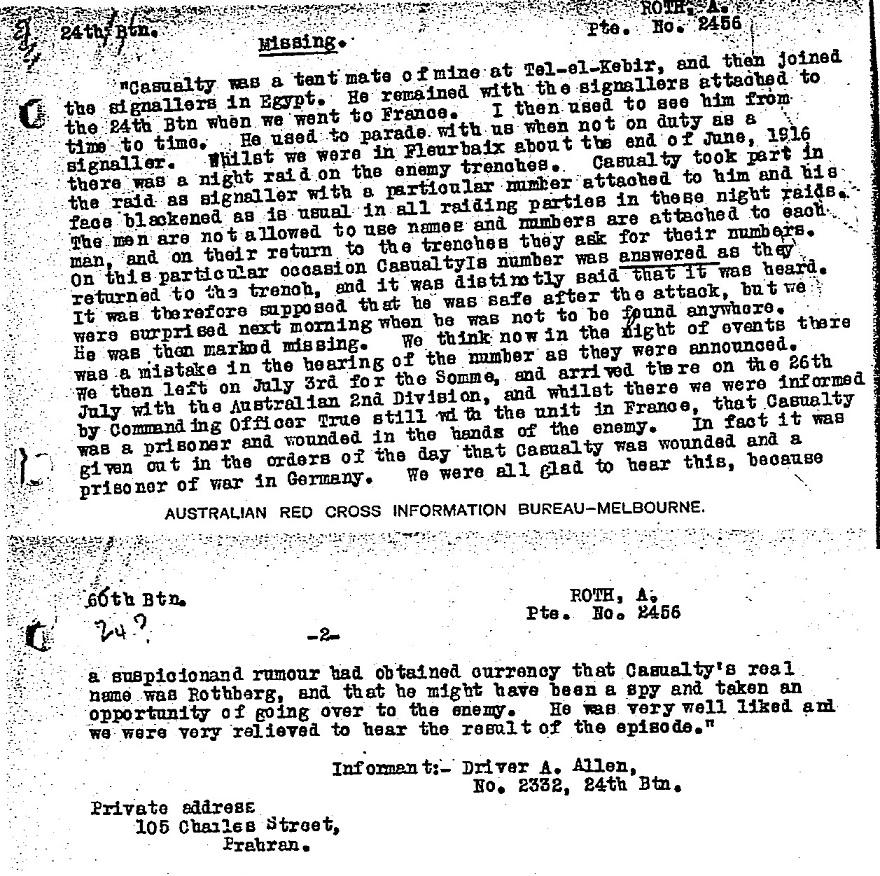

Albert Roth was a signaller for the left raiding party and assisted Lance Corporal Leslie Greaves who was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) for his actions that night. Their role was to establish and maintain telephone communications between Lieutenant Carvick and the commanding officer of the raid, Captain Aubrey Roy Liddon Wiltshire (22nd Battalion), who was back in the allied trenches. Greaves and Roth were to remain in no man’s land or near the German parapet but not to enter the German trenches themselves. From information in Roth's Red Cross Wounded & Missing file and Greaves DCM recommendation, it appears that during the 10 minutes of the actual raid, Greaves was working near the parapet at the telephone and Roth may have been working further out in no man’s land laying and maintaining the phone lines. Although some accounts say he was at the phone near the German trenches, given it was dark and his face blackened, it is possible some eye witnesses mistook Greaves for Roth.

Greaves was wounded during the raid but remained at his post. It was reported second hand that Roth was seen in no man’s land while shells dropped close by. Another account stated that one of the scouts for the raid last saw Roth in no man’s land about 73 metres from the German trenches. When the party returned to the allied trenches, Roth's ticket was apparently noted and it was initially believed he had returned, but it was later discovered he had disappeared. Despite searchers going over no man’s land again, no trace of him was ever found.

Rothberg the spy?

Roth’s disappearance under these circumstances led to a rumour spreading through the 24th Battalion that Roth was a German spy called Rothberg who sabotaged the raid and deserted to the enemy.

Those that knew him well reported there was no credence to the rumour and they believed he was either a prisoner of war, or killed during the raid. However, certainty in the battalion that all those wounded or killed had been found and brought back contributed to the idea he had deserted. The mistaken signal to withdraw during the raid was regarded by some as proof he was a spy. His Germanic surname could have also contributed to this idea given the anti-German sentiment prevalent in Australia at that time. Whether Roth mistakenly gave the order, someone else did, or even if the word was misheard during the raid will never be known.

Interestingly, another soldier, Private John Bull of the 21st Battalion went missing that night in no man's land – he was in a covering party for one of the other raiding parties. As with Roth, search parties failed to find his remains. However, unlike Roth, there was never any question that he deserted or was a spy and his unit believed he was killed or taken prisoner. Based on witness statements and the shelling that took place that night, it seems most likely that both Roth and Bull were killed by shells and their remains unidentifiable.

Unfortunately, the belief that Roth caused the battalions withdrawal and that he was a spy continued to permeate through the battalion. Although he is not named in the 24th Battalion authorised history “Red and White Diamond” by W J Harvey, published in the 1920s, the event is mentioned and the author continued to perpetuate the false story about Roth’s disappearance, despite Roth officially recorded in 1917 as being killed in action. The author wrote:

“…An interesting and suspicious incident marked this adventure. One of the raiding party disappeared. The word “Bunk” was to be the signal to retire in case of an outflanking movement by the Boche. Scarcely had the raiders gained the enemy line when that order was passed along. The men immediately fell back, as they had been instructed to do. Nobody knew who had given the order, and it was quickly realised an act of treachery had been perpetrated. The order was at once given to re-enter the German position, and the men dashed over the parapet again to complete their job which they did with marked success. The man who had disappeared was never seen again, and inquiries led to the conclusion that this individual, whose nationality was afterwards doubted, was responsible for the unexplained interruption…”

Officially Roth was not credited with the error. In Volume III of the official history CEW Bean does not speculate on who gave the order to fall back and simply notes that “…there was a temporary falling back through the signal to retire (the word “bunk”) having been given by some unauthorised person…”

Lieutenant Kerr wrote an account of the raid in a letter home on 1 July 1916 (a copy is held in the Memorial’s Research Centre at 1DRL/0397). It is full of detail about the raid but he appears to have self-censored as he makes no mention of the “bunk” incident. He does however mention Roth’s disappearance. He wrote:

“…”All in?” No! four [sic] have not yet reported. So out go five men and we two Officers [Kerr and Carvick], and caring nothing now for flares or bullets walk out over that field of death to see if we can discover any trace of the missing.

We are certain we left no one in the German trenches and just as certain that there is no one lying between the lines. After a ten minute look round, we returned, to find that three of the four are alright, which leaves one missing. We can’t find out what has happened to him…”

While another rumour went through the 24th Battalion that Roth had been taken prisoner and was alive in Germany, his name never appeared on any POW lists and Roth was officially listed as killed in action in September 1917, over a year after his death. With no know grave his name is commemorated on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial.

A full account of the raid is in Volume III of the official histories (pages 27 - 28 of the scan for details about the raid on the night of 29/30 June) and a copy of the operational order is held in the 6th Brigade war diary (pages 21-23).