Songs of Survival

Slim de Grey was left devastated when his best mate was taken from Changi to Sandakan during the Second World War.

The pair had been captured by the Japanese after the Fall of Singapore and herded into the camps at Changi along with tens of thousands of other British and Australian prisoners of war.

Slim tried in vain join his mate, but was not allowed to go because his work with the AIF Concert Party at Changi was deemed essential in boosting morale amongst the prisoners.

It was a decision that would ultimately save Slim’s life.

Today, the Sandakan death marches remain the greatest single atrocity committed against Australians in war.

Of the nearly 2,500 Australian and British prisoners of war who were sent to Sandakan on Borneo’s north-east coast during the Second World War, only six survived.

Slim would never see his best mate again.

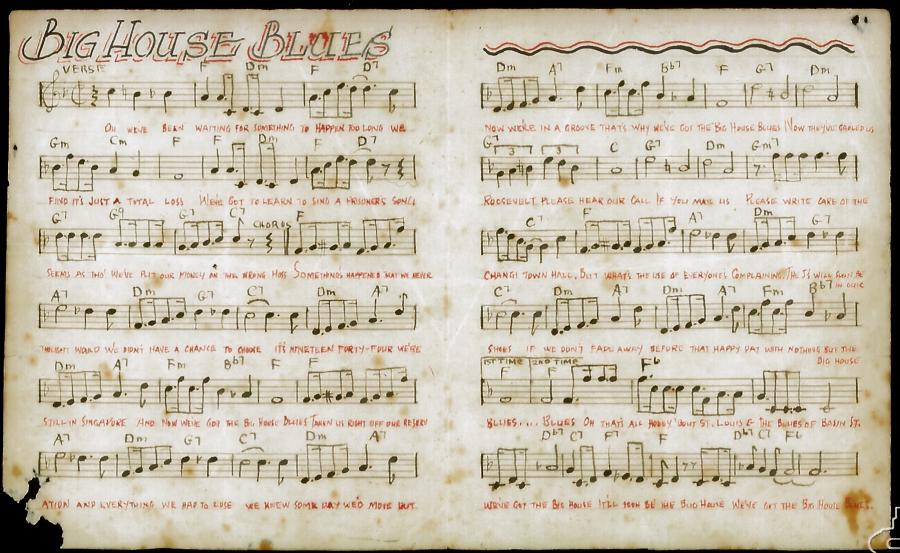

He composed the song They’ve Taken My Old Pal Away shortly after his friend was shipped to Sandakan in 1942 to build an airstrip for the Japanese.

The song put into words how many of the prisoners at Changi felt about being separated from their mates after being together for so long.

More than 75 years later, the song will be performed by Slim’s friend, actor Neil Pigot, as part of the POW Requiem in Canberra on 29 October 2022.

The fourth in a series of commemorative concerts, the requiem uses powerful music and imagery to tell the stories of the men and women who were prisoners of war and internees during the Second World War.

Directed by the Australian War Memorial’s Musical Artist-in-Residence, Christopher Latham, as part of the Flowers of Peace project, it aims to create a deeper understanding of the prisoner of war experience while highlighting the importance of music and culture in keeping up morale.

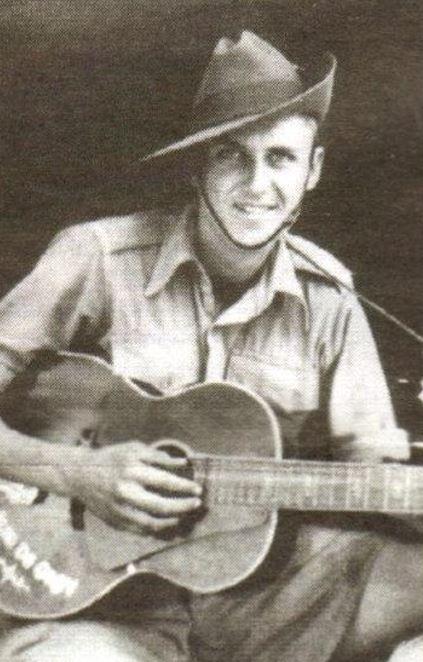

Slim de Grey would go on to become one of Australia’s leading stage comedians after the war and was often credited with introducing stand-up comedy to Australia. But he first started performing as a prisoner of war at Changi.

He would tell jokes for the next 60 years, remaining on the boards for the rest of his life. Known for his singing, dancing and acting, he became a household name in Australia, starring in some of the country’s best-known television shows and feature films of the 1960s and 70s.

“I learnt the bloody lot,” he once said. “Because in those days you wouldn't get a job unless you could tap dance, play the piano, sing and tell a joke.”

Clifford Frank de Grey was born near Blackpool, England, in May 1918, but took the stage name Slim after the war because he thought it sounded more American in the days when overseas performers were rated more highly than the locals.

His family had emigrated to Australia when he was six years old and settled in Sydney.

He became an apprentice baker when he left school, working with his father, but life as a baker didn’t suit him. “While I was at the bakery I must have thought subconsciously what I could do to avoid getting up early in the morning.”

Slim taught himself guitar and harmonica after seeing the then unkown singer Tex Morton busking in Sydney. Slim was learning to tap dance when the war broke out.

He was serving as a private with the 2/10th Field Ambulance in Singapore when it fell to the Japanese on 15 February 1942.

He was one of more than 15,000 Australian prisoners of war who were taken prisoner in Singapore and marched into camp at Changi.

Just two days later, an Australian Concert Party began rehearsals for its first show. It was the beginnings of what would become known as the Changi Concert Party.

Initial concerts featured a succession of artists performing individual acts, but before long a party of about 30 full-time performers was formed, moving into an open-sided steel-framed garage, which was gradually adapted as a theatre, complete with elaborate backdrops, curtains and theatre lighting.

The materials used to transform the garage, as well as some of the costumes and musical instruments, were scrounged by prisoners who were on work parties outside the camp, and by small parties of men who went through the perimeter wire at night.

At one stage, they even had a 14-piece orchestra using instruments that work parties had obtained outside the camp, before dismantling them and smuggling them in.

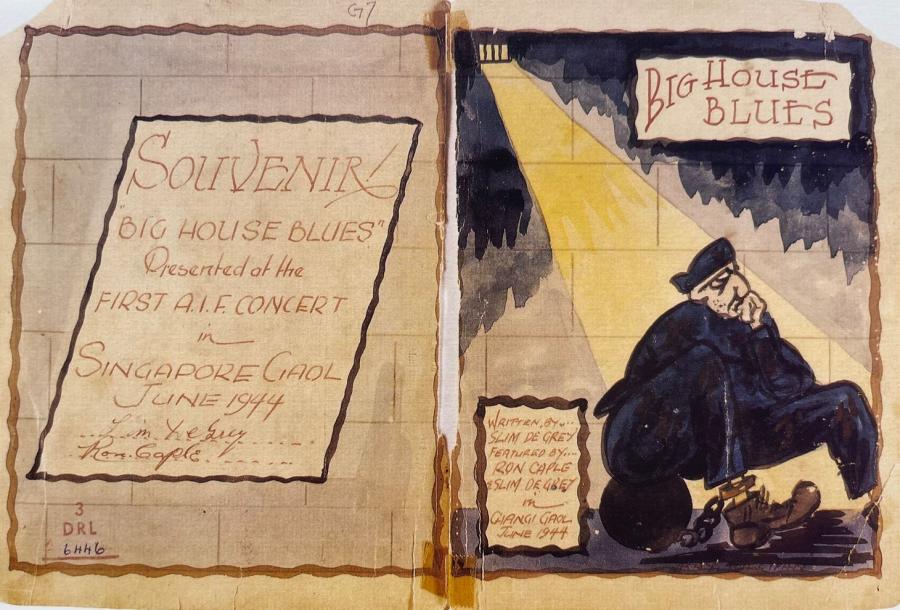

For the next three years, Slim and his mates wrote songs and sketches with illegally scrounged paper and pencils to raise morale and lift people’s spirits.

Their increasingly professional shows ranged from individual acts, with comic and vaudeville routines, to popular songs and musicals, many of them written in the camp, as well as serious dramatic performances and a traditional pantomime each Christmas.

Amid hardship, the Concert Party at Changi put on more than 240 theatre shows.

The shows were a highlight of the week and became so popular, not only with the prisoners but also with the Japanese, that tickets had to be rationed and a roster system put in place to ensure everyone could see a show. Former prisoners said it was the only time they forgot how hungry they were.

Ray Tullipan was a private in the 2/18th Australian Infantry Battalion. He was one of the main songwriters in the Concert Party at Changi.

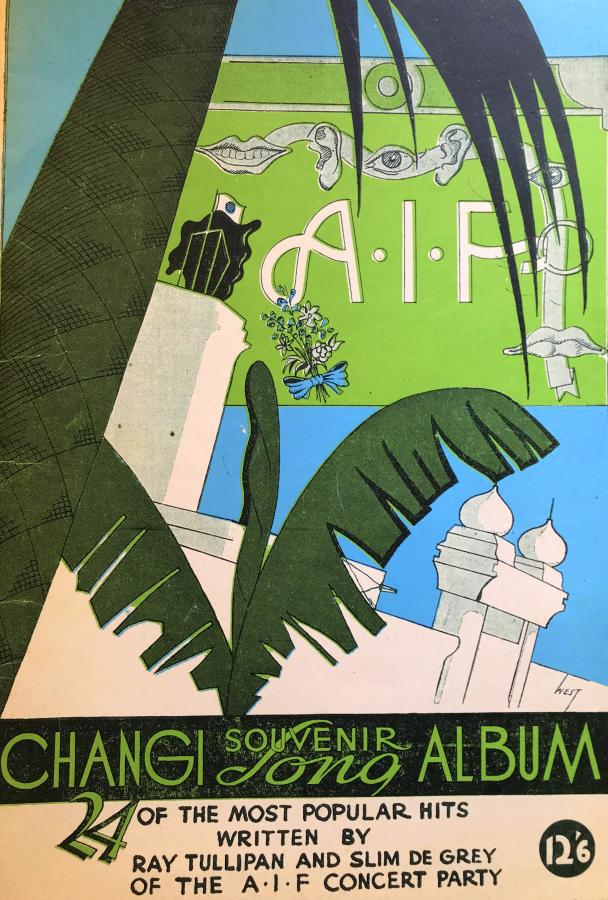

After the war, Slim and his mate Ray Tullipan, the other main songwriter at Changi, printed the most popular songs they had written in a book they called the Changi Songbook.

The book featured the 24 most popular songs as chosen by prisoners at the end of the war, and were printed as a souvenir booklet when the pair returned to Sydney.

Copies of the book were sold to former prisoners and were so beloved that it remains difficult to source a copy, even today.

Slim went on to write a book about his experiences, The Funny Side of Changi, and in 1993, Slim and two other Changi performers, Jack Boardman and Keith Stevens, recorded a selection of the songs on an album, the Changi Songbook, funded by actor Neil Pigot.

Pigot first met members of the Concert Party in Tasmania in 1992 when he was performing in A Bright Crimson Flower, which chronicled the experiences of six young Australian prisoners in Singapore, Burma and at Changi.

“Slim was just a lovely man,” Pigot said.

“He came to the opening night and he and I just hit it off.

“We went to the pub afterwards, and I said, ‘I would like to record an album of the songs,’ and he said, ‘You know, we’ve never done that,’ so I decided that we would.

“There was me, Slim, Jack Boardman, who was the orchestra leader at Changi, and Keith Stevens, who was a sergeant with the engineers and a burlesque female impersonator at Changi.

“He co-wrote Twinkle Toes, which is a musical from which a number of the songs come from, with Slim.

“Slim couldn’t read music so he used to sort of sing the songs to Jack, and Jack would notate them.

“When it became clear that they were about to be liberated, Slim and Ray cooked up this idea ...

“They put envelopes around the camp for people to write down what their favourite song was and then when they got back to Australia, they collated them, and created a kind of a hit parade, or a list, of what the most popular songs were.

“They put those 24 songs into the book, and for about six months after they got back, Slim and Ray toured around regional New South Wales and into Queensland performing the songs.

“They had a blanket, Slim told me, and people would throw money onto the blanket, and that was the basic genesis of the actual book itself.

“Slim had started writing original material when he was actually in training in Holsworthy.

“And then at Changi, there was just a demand for something different.

“As one guy said, ‘There’s only so many times you can listen to Red River Valley,’ which was a popular song of the period.

“They didn’t have a lot of original material with respect to plays and that sort of thing [when they started performing at Changi], so originally they were just doing reviews with a bit of comedy and whatever songs they knew.

“But then the demand for something new that also reflected the reality of the situation they were in [at Changi], led to the development of new material.

“If you listen to the songs, most are about hope and about the idea of one day returning to normal life.

“They were almost completely stripped of anything that we would regard as being human, and so the only thing that they could really turn to was their imaginations and the hope that came with that.”

For many prisoners, the Concert Parties proved to be a lifesaver.

The wartime surgeon Sir Edward "Weary" Dunlop even credited the Concert Party at Changi with saving as many lives with its morale-boosting work as the medical team.

“There was the suggestion that if a man decided he’d had enough, he would slowly die, and so the Concert Party was [vital] ... in the pressure cooker that was the POW experience in South-East Asia,” Neil said.

“They reckoned if a man stopped laughing, they started to worry.

“But when they came back, our focus on the POW experience was largely on the privation, the terrible conditions they’d been in, and the heroes of the piece as it were, became the doctors ... Albert Coates, Weary Dunlop, and people like that.

“And yes, they played an extremely important role, but the role of the Concert Parties, which were everywhere, was not something we took any real interest in. Yet without them, the doctors would have been struggling to keep people alive.

“Brigadier Galleghan [the commander of Australian prisoners in Changi] coupled the work of the Concert Party with that of the doctors, in the sense that the doctors kept the men physically well, while the Concert Party kept them mentally well.

“So, yes, humour was vitally important ... fiercely important, and that’s what Slim really was, a comic.”

After the war, Slim appeared on the BBC in Britain alongside French singer, actor and entertainer Maurice Chevalier. He co-produced Australia's first television variety show, Cafe Continental, for the ABC from 1958 to 1961. He got his first big break in the comedy They're a Weird Mob in 1966, and appeared in a host of well-known television series, including Skippy, Homicide, Matlock Police and You Can't See Round Corners. He also starred in feature films such as Age of Consent with Helen Mirren, Wake in Fright with Chips Rafferty, and Newsfront with Bill Hunter. He even had a small part with Paul Hogan in Crocodile Dundee in Los Angeles. There was barely a TV series made in Australia at the time that did not feature him.

His last acting role was in the 2001 ABC production Changi, in which he effectively played himself, a digger called Old Curley, whose later life was coloured by his wartime experiences. He was the only Changi survivor in the production and gave younger cast members history lessons before filming began. It was a fitting finale.

Slim won four Mo Awards for entertainment and was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

He died in March 2007, aged 88.

All 24 songs from the Changi Songbook were recorded together for the first time earlier this year as part of the Flowers of Peace project.

Nine of the songs will be performed as part of the POW Requiem.

“They would have been chuffed,” Pigot said.

“I knew a lot of these guys ... and they were all just quiet, humble men.

“When they returned, they were never held up as having really achieved very much during the war – they were captured, and they spent three and a half years as prisoners, and then they were released – but in there they created a civilisation, an incredibly complex and nuanced civilisation behind barbed wire that is remarkable.

“They didn’t earn VCs and charge at things, but they had the courage to get up every day and go through it all again, and support each other in that, and that’s extraordinary.

“The Concert Party was a vital cog in that wheel...

“So they’d be chuffed to know we were talking about the complexity of their experience... because what the songs embody is not just the Concert Parties, but that slow-burn courage that these 22,000 Australians applied to three and a half years of captivity.

“We tend to focus on the negatives of the experience ... on the deprivation ... on the maltreatment... on all those things, but we tend not to focus on how they managed to get through.

“The songs reflect the hopes and dreams of those men as prisoners of war and chronicle their experiences over three and a half years of captivity, but musically they’re quite beautiful as well.

“We tend to think of our military experiences a lot of the time in terms of numbers, and guns and tanks and aeroplanes, and this happened and that happened, and what can get lost in that is the humanity of the experience.

“But one of the things that the songs do – in a way that not much else can, really – is that they create a window to the human experience.

“They open up our capacity to empathise in a way that numbers don’t.

“And you cannot help but be moved by that.

“The fact they survived in the numbers that they did is a testament to the courage of the men, but also to the nuances of their experience.

“So for me, to see people getting a connection to that human experience is extremely gratifying.

“All they wanted really was that recognition of that human experience."

The POW Requiem is on Saturday 29 October 2022, from 1pm to 4.15pm at Llewellyn Hall at the Australian National University in Canberra. For more information visit: flowersofpeace.com.au