Inked: Tattoos and the Military

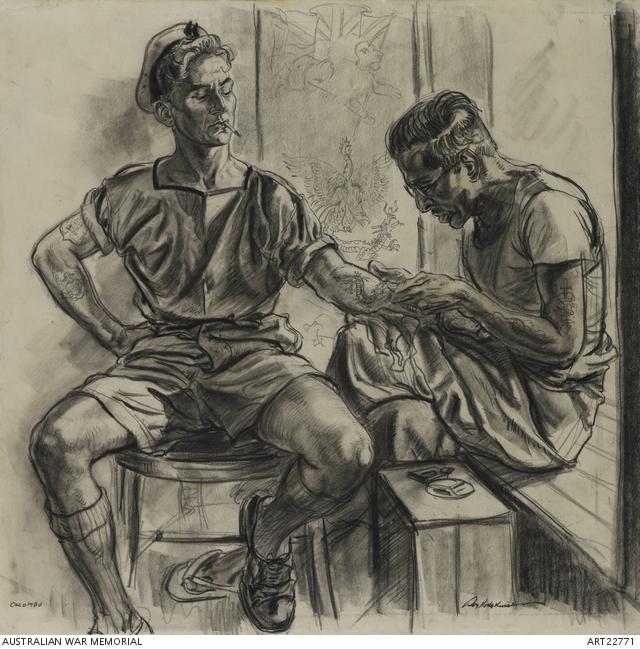

Australian matelot and Sinhalese tattooist.

black crayon with pencil and wash on paper.

Roy Hodgkinson.

From the First World War to reality TV, tattoos and the art of tattooing have captured the imagination of many. Where tattoos were once the sign of a sailor or rebel, they have now become widely socially accepted. This article explores the history of tattoos in the military by exploring their origins and meanings, and their representation in the Memorial’s photograph collection.

Whether tattooed or not, almost everyone has a tattoo story. An estimated 19% of Australians have a tattoo according to one study, while Canberra, a relatively small city, was home to twenty-six tattoo parlours at last count. According to Wikipedia, there are about ten tattoo related TV reality shows in production at any one time.

But tattooing is in fact an ancient practice, as shown by tattooed mummies in Egyptian tombs, or the c.5000 year old, Bronze- age body found in Europe, bearing fifty seven tattoo markings. Over the centuries, tattoos have been used in a variety of sometimes contradictory ways: to provide protection against bad luck and ill health, and to punish; to demonstrate devotion to religion, or commitment to a cause, or membership of a tribe or community. Tattoos can mark people, both literally and figuratively, as holding an important belief or belonging to a certain group. Sometimes those two things are one and the same.

Today’s advanced techniques allow an individual to choose from or personally design images of incredible complexity. Sometimes these images embody, or even commemorate, experiences which profoundly affected the person who selected those images. Military men and women can be profoundly affected by their experiences of deployment, including personal joys, such as the friendships that form in teams and units; hardship, such as separation from home; or tragic loss, such as the death of a friend. In the wider community the desire to remember or commemorate friendship, love and loss can be just as strong for those who haven’t served. Tattoos are worn by civilians as a way to pay tribute to spouses, friends, relatives and ancestors who served.

Seafaring and endurance

Although European sailors and colonists would have seen tattoos worn by indigenous Americans, the first modern record of tattoos is thought to be from James Cook’s expedition to Tahiti (1769), though early colonists of the Americas would have seen the tattoos of the indigenous people there. The word ‘tattoo’ is thought to be adapted from the Tahitian word ‘tatau’ , which means ‘marking something’.

European seafarers noted how other cultures used tattooing as a rite of initiation for boys entering manhood. By the Victorian era, ‘Sailors endured the pain of the tattooing process as a way of asserting their masculinity over their peers. It soon became a competition for dominance as no sailor could be perceived as weak’. Soldiers too, were to take up the challenge.

The World Wars

As this quote from The Gundagai Independent and Pastoral, Agricultural and Mining Advocate shows, by the time of World War I, tattoos were synonymous with military life.

One of the vanities of our gallant defenders is tattoo ornamentation. A few months ago.. I was chatting with a soldier who was a regular perambulating picture gallery. His body was literally covered with representations of flags, animals and notorious characters; when I remarked on the extraordinary manner in which his skin was decorated he became quite confidential. ‘They were done when I was in India’, he said.

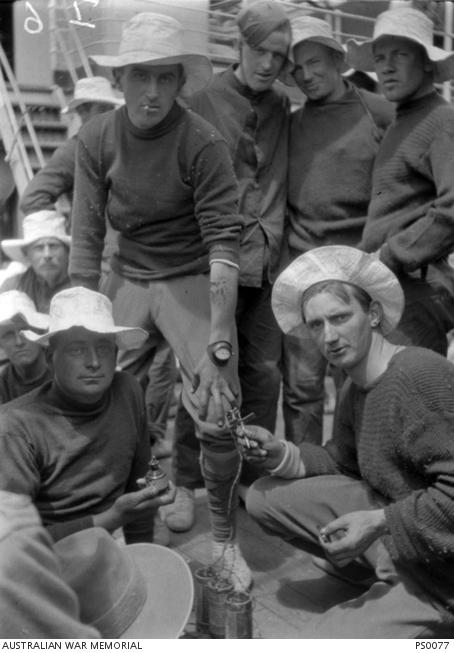

Taken around 1915, this photograph shows of a group of Australian soldiers on the deck of a ship, probably on their way to Egypt.

We owe thanks for this remarkable image to Philip Schuler, a young Australian journalist for The Age, who covered the Gallipoli campaign.

A group of soldiers on the deck of a ship looking at a just completed tattoo, the soldier "tattooist" and his tattooing equipment of electric needle, three batteries in series and a bottle of ink .(One of three photographs in a series see PS0075, PS0076, PS0077).

The tattooist can be seen using an electric needle, three batteries, and a bottle of ink. One can imagine that this would have been an interesting way for the lads to kill time on a long sea voyage, either by getting a tattoo or watching someone else get one - so long as the sea remained nice and calm!

The image is difficult to interpret, but the tattoo represents an animal, possibly a ‘British bulldog’.

Australia at this time considered itself very firmly a part of the British Empire, and a 1917 issue of Gundagai Times & Advertiser provides insight to the Australian experience via this London-based article:

Mr. Burchett, tattooist, is one of the busiest men in London. He has recently opened a second establishment.. so as to be able to ornament indelibly the .. bodies of the men of his Majesty's forces. 'I have twice as many clients now as I had before the war.. Most of them are soldiers or sailors.. A good many soldiers bring me photographs of girls to tattoo; but this is not always wise, because sometimes it’s a case of off with the old love, [but] you can’t get her off your arm. Why, I’ve done three different girls' heads for one soldier. Each insisted on being there when she saw the picture of her predecessor. ..Seven and sixpence gives you a nice, smart, patriotic design, but, of course, if you want a portrait and perhaps two hearts with an arrow through them or something tasty like that, it costs more’.

‘Very smart these,' said Mr. Burchett admiringly. 'Takes only ten or fifteen minutes to have any of them on your skin for life. It's wonderful when you think of it.'

It’s plain to see that the new, battery powered tattoo technology is well established by WW1, while the War itself precipitated the tattooing of men and even women in unprecedented numbers. Some observers even credited the increasing trend directly to the war itself.

While tattoo technology had advanced, hygiene still had a way to go.

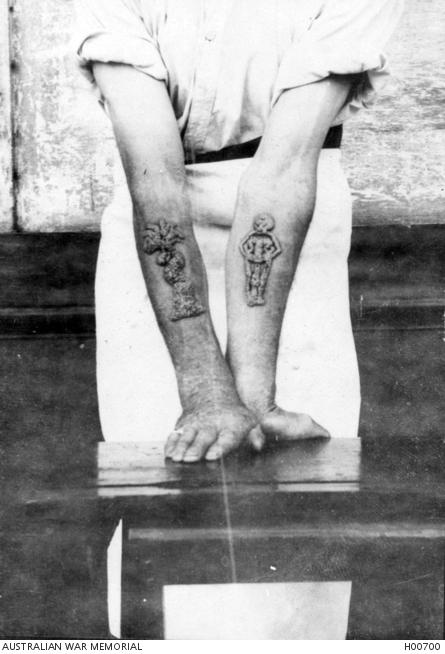

This image, dating from WW1, shows what can happen when a tattoo becomes infected, most likely by “golden staph” (the Staphylococcus virus), resulting in a genuine “tattoo nightmare”:

An infection in both arms caused by tattooing (Adam and Eve).

The infected tattoo was part of a series of images of medical conditions and hospital scenes. Tattoos, at least in a military context, were not usually sought by photographers in this period and the Memorial doesn’t hold many photographs of tattoos. However tattoos are recorded in other ways.

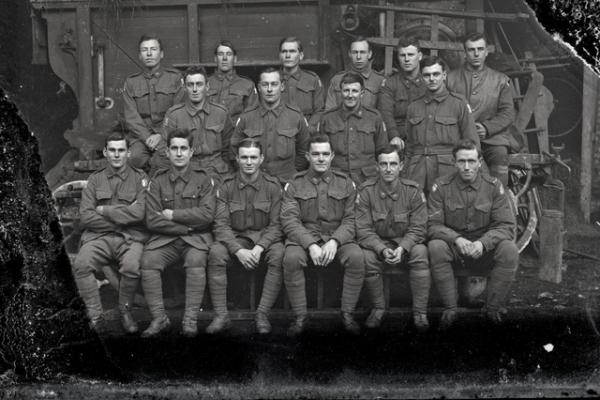

Sergeant John Spence (the first on the left in the front row), was, like all army enlistees, examined by a medical officer. The officer was responsible for recording all distinguishing marks, and he made the following notes in John Spence’s attestation papers:

- On back : Eagle & Australian flag

- On chest : Australian coat of arms

- Left arm : “Advance Australia”

- Right arm : “Unity”

- Left forearm : [some initials] “ M.T.”

- Both arms : A swallow

John had quite the tattoo collection!

Stay tuned for the next installment of Inked, which will look at tattoos in WW2 and beyond.