“We had to walk and walk the endless road to a CALVARY.”

Chrisoula Borda (née Bochoyianaki) was 16 years old when war came to Crete in 1941. A courageous young woman, inspired by faith, she immediately tried to help, bringing food and supplies to prisoners of war. First she helped the wounded Italians and then, following German occupation of Crete, British and Australian prisoners. She helped free a prisoner of war (POW), ‘Freddy’, only to be betrayed by her oldest friend to the Germans. She and her sister Anna were tortured and imprisoned, moved around Europe to a series of prison camps - including twenty months at Auschwitz - before she was free again.

Chrisoula and her family eventually moved to Australia in 1968. Throughout her life, Chrisoula struggled to accurately express her experiences of being a captive of the Germans. However, she still desired to tell her story. Although in her 70s and her English was limited, Chrisoula taught herself to type and used Greek, German and English dictionaries to translate her words.

The resulting memoir is a remarkable story of courage and faith, leavened with moments of compassion and Chrisoula’s irrepressible senses of humour and righteousness. The Australian War Memorial is pleased to be able to present her story and allow her words to be read and heard.

Chrisoula introduces us by writing of her brother and friends going to war, while English, Australian and New Zealand troops garrison the port of Heraklion. The relatively mild bombing raids by Italian aircraft quickly changed after the German invasion began. She describes the air battle as scenes from hell.

“They hit simultaneously every English base and the Island seemed to be shaking from end to end, as if hell was turning upside down, that made the previous bombing look like fireworks.

After all that intensive bombing, the bombers were replaced by planes and each of them was towing two/three gliders full of parachutists, and the sky was dotted with white and olive green parachutes. There were thousands of them.”

Crete,1941. German paratroops, part of the German airborne invasion of Crete, parachuting onto the village of Suda.

The Bochoyianaki family survived the initial stages of the invasion, able to stay with some Commonwealth forces in their bunkers near the airport. But by the 9 June 1941, the British forces had withdrawn from the island. The Battle of Crete had lasted eleven days. Chrisoula describes the effects of the battle on the streets of her home in horrible detail.

“German and English bodies and parachutes were everywhere. Hanging on trees, on electric poles, walls of ruined houses, and the ditches and side of the road, and we watched those hanging on the trees and poles swinging back and forth in the May breeze. They looked pitiful.”

The town of Heraklion on the north coast of Crete, being bombed by the German Luftwaffe during the German airborne invasion of the island.

After the fall of Heraklion to the Germans, Chrisoula brought food to British and Commonwealth troops in the nearby Prisoner of War camp. Hearing that some POWs were managing to escape to Egypt, she decided to help break out one of the men, ‘Freddy’. She persuaded her best friend’s mother to make some civilian clothing for him, screws up her courage - and walked Freddy out, shivering despite the warm summer.

Chrisoula and her family are able to conceal Freddy in their house for some time, with the assistance of friends. Together, they make plans for Freddy to escape to Egypt but are betrayed by neighbours - hours before their plans could be implemented.

Chrisoula and her older sister, Anna (18), were imprisoned. Chrisoula describes the torture of the German officers. Despite being beaten nearly to death, Chrisoula steadfastly refuses to admit any complicity by the rest of her family in the escape and concealment of Freddy.

Over the next years, Chrisoula and Anna Bochoyianaki and their fellow prisoners suffered imprisonment, privation, and torture at the hands of their captors. They are moved to a succession of prisons and camps across occupied Europe, first in Greece and then the former Yugoslavia, including internment in the Sajmište and Banjica concentration camps.

Eventually, the sisters and their friends were transported to Auschwitz concentration camp. The train was severely overcrowded, and they were forced to travel with the bodies of those killed by the guards.

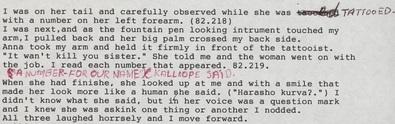

“I was on [Kalliope’s] tail and carefully observed while she was tattooed with a number on her left forearm. (82.218)

I was next, and as the fountain pen looking instrument touched my arm, I pulled back and her big palm crossed my back side. Anna took my arm and held it firmly in front of the tattooist. “It won’t kill you sister.” She told me and the woman went on with the job. I read each number that appeared. 82.219.”

The next twenty months are unmitigated horror. Chrisoula writes of the endless, brutal work, the cruelty of the camp’s kapos, mass executions, beatings, and the grotesque experiments of Nazi doctors. The unrelenting suffering is such that Chrisoula forgets almost all of the details of her life, so focused she is on keeping her sister and herself alive, including even the Lord’s Prayer.

“I didn’t know what to do. Just stood there at the bottom looking at the tip of that pyramidal shape, and in confusion I did the sign of the Cross. I wanten to pray but I couldn’t remember the Lords prayer exept...(PATER IMON O ENDIS URANIS)(=Our father which art in heaven)”

After twenty months in Auschwitz, Chrisoula and Anna were removed to Ravensbrück concentration camp in Germany, where the conditions were better and the inmates worked in a factory. There, Chrisoula and her sister recovered some of their old spirits and memory despite the oppressive circumstances.

Following the end of the war, Chrisoula and her friends slowly made their way home. Post-War Europe was in chaos, and their journey was scarcely less horrible than her experiences in the German camps. Nevertheless, they eventually returned to Crete and to memory.

“I put my hand on her mouth and showed her my missing tooth, and my scared cheek. ‘Anna; I remember! I remember everything! I remember mother, our shop, Alec from Scotland, Jim from Liverpool, Bob the Australian, Captain Cooper, Uncle Bill, Freddy... and all our friends; and I wish they are all alive like us, Anna.’

Chrisoula ends her memoir by reflecting on the post-War years, the friends she lost, and the courage of those who volunteered to help. Her closing words call for the readers of her words to remember the sacrifices of others and to resist those who would destroy “what all those millions of our people die for. For yours and your children’s freedom.”

Chrisoula’s story is a remarkable story of courage and faith. Despite moments of horror, she never truly loses faith with herself, God, or in others. She readily acknowledges the grinding horror of war on all those affected by it, even those who she would have had every right to loathe. Together with her sense of compassion is the humour and animus of a courageous teenager. It is a privilege to be able to read her account. The Australian War Memorial is richer for holding it.