Wearing patriotism

Elsie Myra (Judy) Richards of Newcastle, pictured here in September, 1942, is operating a lathe in a munitions factory. A row of 20-pounder anti-tank shells sit in the foreground.

The needs of the factory worker

In Britain and Australia during the Second World War, the head scarf worn by the munitions worker was adopted for pragmatic reasons, more than fashionable ones. It became a key item of safety wear, functioned to hide unkempt hair, and could add a splash of colour to a plain, ill-fitting uniform or overalls.

The unofficial nature of some industrial work meant a range of everyday clothing was at time worn by civilian workers in less dangerous areas. Loosely-fitted clothing, jewellery, bulging buttons or long hairstyles posed serious risks to women operating machines. In the munitions filling stations, strict rules prevented the wearing of metal (hair clips and jewellery) and workers were provided with fitted danger suits and snoods.

The practice by women of wearing head scarves or a protective cap grew from these safety concerns. In July 1942, the New South Wales Newcastle Sun reported on the proposed state government regulations to forbid the wearing of long hair in favour of a short bob style. As hair was particularly prone to entanglement in machines, the Sun cited the following incident to emphasise the inherent dangers of factory work:

The danger to women in factories was emphasised recently when the long hair of an employee at a northern munition plant escaped from the net she was wearing and became caught in the plant. She was seriously injured.

While some factories provided workers with safety hats or hair nets, otherwise known as a “snood”, some women bound their hair with a scarf knotted at the forehead. Plain or patterned head scarves formed part of the uniform of the wartime civilian labourer in munitions factories and on farms.

Mrs Cara McKay of the Australian Women’s Land Army, Burwood, New South Wales, March 1943.

From the factory to the fashion house

As with many of the trends of the time, civilian workers continued to wear their scarves outside of work hours. British textile designers found a ready market for their bold, patriotic fabric designs. Wearing patriotic prints in the form of square head scarves was one way that some women sought to express their support of the war effort.

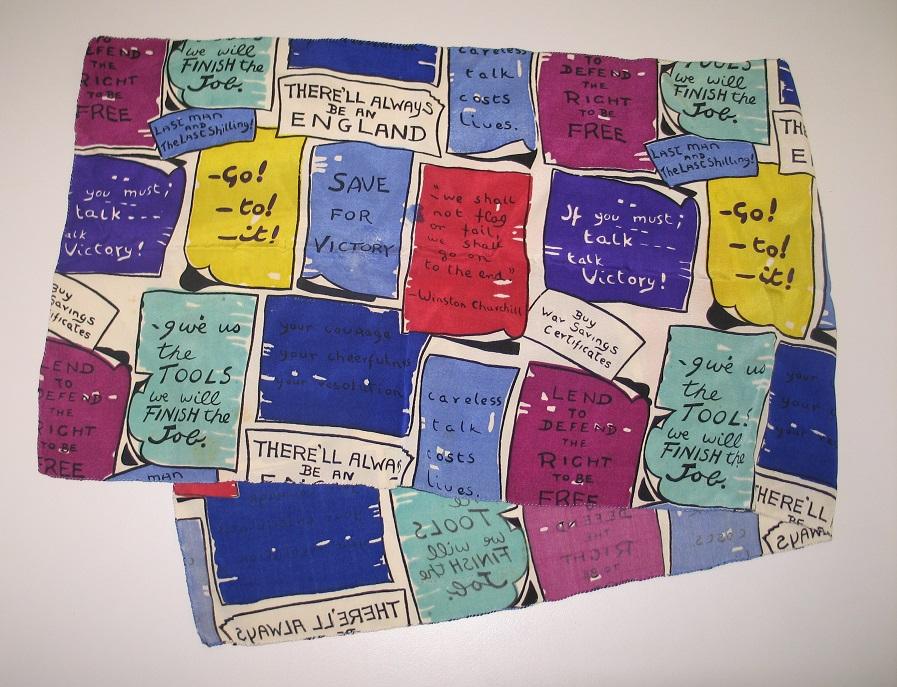

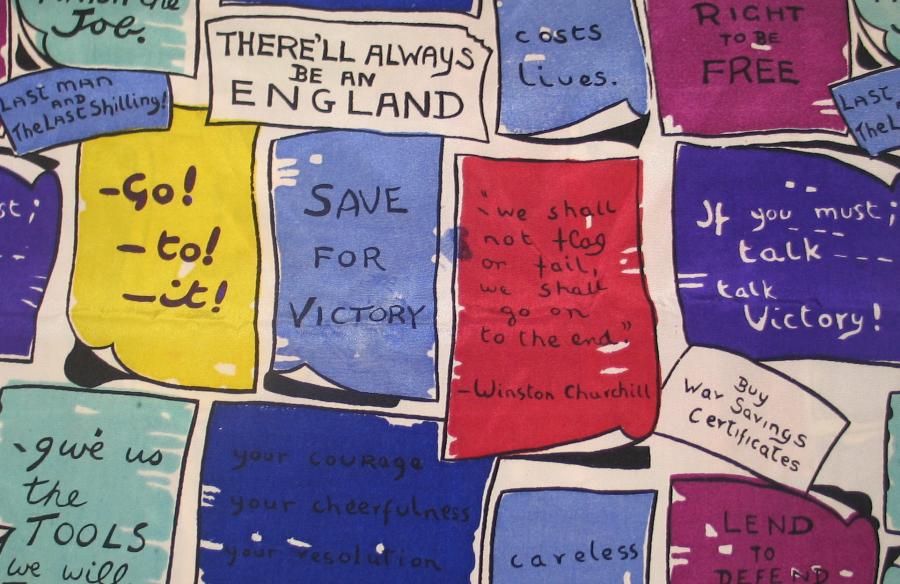

During the war the high-end fashion house Jacqmar of Grosvenor Street, London, produced a range of patriotic textiles that have become synonymous with British home front fashion. Of all of Jacqmar’s designs, the iconic London Wall, a colourful collage of Winston Churchill’s victory slogans designed by Arnold Lever, found its way to Australian shores.

Jacqmar fabrics were expensive wartime commodities. Because most working or middle class British women could not afford to buy silk due to inflation and government rationing, Jacqmar produced cheaper versions of their designs in rayon and nylon for one fifth of the price of silk for domestic and export markets.

The London Wall design enjoyed international success. Worn by famous actresses including American-born Francis Day and British actress Vivienne Leigh, it was a feature of a 1942 article by Vogue on patriotic textile prints. Mrs Churchill was also reported to have worn a London Wall scarf. In June 1941, Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies returned from an official trip to England with two London Wall scarves in tow for his wife and daughter Heather. The scarf given to Heather Menzies was an official gift from Winston Churchill’s daughter, Mary. This very scarf was for a time on display at the Museum of Australian Democracy in Canberra in 2015. During a conversation with Heather, she confirmed that she had worn the scarf and continued to wear it throughout her adult life.

Although Jacqmar prints were widely worn in Britain and America, it is unknown to what extent they were actually worn by ordinary women in Australia. An article in the Advocate newspaper in April 1941 describes the availability of London Wall scarves in a Melbourne shop, confirming their commercial availability here. In late 2012 the Memorial acquired a London Wall rayon scarf for its collection. It was worn by Miss Vera Anderson of Mosman, Sydney during the war, who “drove jeeps around Sydney” as a volunteer.

If you have any information regarding Jacqmar designs in Australia, I would like to hear from you.

By Eleni Holloway, Assistant Curator, Military Heraldry & Technology

Further Reading:

Atkins, Jacqueline M., Wearing propaganda: textiles on the home front in Japan, Britain, and the United States, 1931-1945. The Bard Graduate Centre for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design and Culture, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007.

Huff, Alexandra B., Beauty as duty: textiles on the homefront in WWII Britain, Printed in the United States, 2011.

McNeil, Peter, ‘Put Your Best Face Forward’: The Impact of the Second World War on British Dress. Journal of Design History, Vol. 6. No. 4, Oxford University Press, 1993.