The historic war site of the Changi Murals: a place for pilgrimages and tourism

Author: Dr Kevin Blackburn

{1} David Lloyd, in his analysis of the origins of battlefield tourism and the beginnings of the mass pilgrimage movement to historic war sites, has described how regular visits to First World War battlefields and cemeteries after 1918 created a phenomenon of "sacred" war sites, where the fallen were remembered on "hallowed" ground. Sites from the war became sacrosanct because they were etched in the collective memory of the visitors' home country as places where young men had sacrificed their lives for their nation. To the pilgrims, the ground was "sanctified" because their relatives or comrades had fallen there.1

{2} John Urry, a sociologist working in the area of tourism, has gone further and argued that "both the pilgrim and the tourist engage in 'worship' of shrines which are sacred, albeit in different ways, and as a result gain some kind of uplifting experience." Urry drew the conclusion that tourism and pilgrimages both involve essentially the same type of "gaze" upon a "sacred object".2

{3} Lloyd has written that at historic sites for the fallen there was an "inadequacy of strict distinction" between the two activities, giving rise to a concern among those making pilgrimages that the presence of tourists trivialised the meaning of the sites. He observed that there was an apparent "postwar dichotomy between battlefield tourist and the pilgrim", but still "many travellers felt that in visiting the battlefields or war memorials they were coming to a sacred place" rather than just stopping by the local attractions. Lloyd concluded that "tourism and pilgrimages represented alternate and overlapping modes of perceiving a journey", and that "both forms of travel were often seen as having a moral purpose".3

{4} Lloyd's and Urry's ideas can be explored by examining remote historic war sites that are perceived to be both tourist attractions and places for pilgrimage, to determine if these two activities at a sacred place coalesce into each other. The Changi Murals at Singapore, located in the tropics of Southeast Asia (far away from the places of residence of many visitors, who come mainly from British Commonwealth countries, Europe and North America), offers an interesting test case for Lloyd and Urry's ideas on the similarities between the tourist gaze and the gaze of the pilgrim. The murals were originally created in a chapel within the huge prisoner of war (POW) camp established in the Changi area by the Japanese after the fall of Singapore in February 1942. The chapel, St Luke's, occupied one end of a ward in the POW hospital that had been set up in a former British army building called Roberts Barracks.4

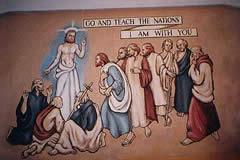

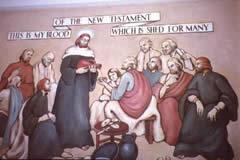

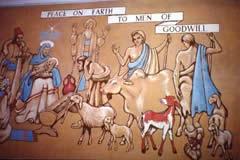

{5} Five near life-size murals of scenes from the New Testament were painted by a British prisoner, Stanley Warren, on two of the chapel's walls between September 1942 and May 1943. On one wall, three murals were painted: the Resurrected Christ with the title "Go Teach the Nations I am With You"; the Crucifixion, bearing the title "Father Forgive Them They Know Not What They Do"; and the Last Supper, with the inscription "Of The New Testament This Is My Blood Which Is Shed For Many". On the opposite wall, Warren painted the Nativity scene, under the phrase "Peace on Earth To Men of Goodwill", and St Luke in Imprisonment, with the inscription "Only Luke is With Me".

{6} The words to go with the murals were mostly chosen by Warren to emphasise a common humanity that the prisoners shared with their captors. A devout English Catholic, he believed that his murals should show the "universality of Christianity".5 Warren was, however, forced to compromise on the wording of the Nativity scene, because of a disagreement he had with Padre J.G.M. Chambers, the priest of the chapel. Chambers had reservations about any impression that might possibly be conveyed to the sick and dying men in the hospital that the Japanese guards, who were depriving the POWs of needed food and medical supplies, shared a common humanity with their inmates. Warren had originally wanted it to say "Peace on Earth and Goodwill to all Men", rather than just "Men of Goodwill", until Chambers advised otherwise.6 To add to the poignancy, Warren used his fellow POWs as models for the disciples, drawing them in the rags they were dressed in and showing their emaciated bodies.7

{7} Pilgrimages to historic war sites, such as the Changi Murals, are a phenomenon of the twentieth century, produced by the two world wars that were fought on an unprecedented scale and in which millions lost their lives. After these wars, veterans and relatives of the war dead started - in numbers no less unprecedented - to undertake what they called pilgrimages, visiting the graves of loved ones and former comrades at far-away battlefields. These pilgrimages commenced soon after the First World War, when tour companies began to offer trips back to the battlefields and war cemeteries in France. Lloyd has made the point that these mass pilgrimages would not have happened at that time except for the growth of the travel industry from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. The availability of packaged tours at affordable rates provided the means for many low-income earners to venture abroad,8 and thus to take part in the re-invention of the religious pilgrimage at battlefield sites.9

{8} This new pilgrimage movement of the twentieth century involves rituals that have a close relationship with the rituals of religious pilgrimages. These new rituals are focused on remembering the war dead, and include religious services conducted for the fallen. The rituals of pilgrimages to the monuments to the war dead, unlike those of most religious sites of pilgrimage, allow for participation by other visitors, such as tourists, who can also join in ceremonies conducted at the site and pay their respects to the war dead. Thus, it may be that tourists and pilgrims at sites to remember the war dead have similar experiences, and in the words of Urry have the same gaze on the sacred object.

Thoughts and feelings of the ex-POWs on pilgrimages to the Changi Murals

{9} Whether or not both tourists and the pilgrims visiting the Changi Murals have experienced the same gaze can first be explored by investigating the record of their thinking that they have chosen to make public in the visitors' books provided by the curators of the site. These visitors' books have been preserved and catalogued since the early 1980s. They are an imperfect source, because they only show what thoughts and feelings the pilgrims and tourists have chosen to reveal, which may be different from what they were thinking due to a consciousness that other people will read their comments.

{10} An examination of the expression of thoughts and feelings in the Changi Murals visitors' book indicates that there are significant differences in what ex-POWs write down and what relatives and tourists express. All of the ex-POWs who took the time to write down their impressions on their pilgrimage surprisingly appeared reluctant to make any emotional remark beyond a simple dedication, such as "10/11/87, For Ex-Roberts Barracks inmate M.E. Wood on behalf of John Wood, W.H. Dickinson, Roberts Barracks 1942". Dick Armstrong, an ex-POW from Australia, in February 1992 wrote, "I knew the artist and the men", and then mentioned a former comrade, "George Lawrence was in this building 50 years ago." Stanley Warren, the painter of the Murals, when restoring them in May 1988, simply wrote the understatement, "revisiting again". Wally Hammond, Warren's ex-POW comrade, only commented, "still very fine Murals. I was here to see the originals painted." Many ex-POWs have written no more than "Lest We Forget". When large groups of ex-POWs have visited the Changi Murals they have all signed the visitors book under the same comment, "Lest We Forget". Arthur Goodison, visiting in November 1988, listed the many Japanese POW camps that he had been held in and then concluded his list with the remark, "Now 71 years. These paintings say it all."

{11} Longer comments from ex-POWs tend to reveal that they are partaking in a ritual of recalling the memory of their comrades. In the case of Arthur Goodison and other ex-POWs, they are also engaged in trying to make sure that the story of their experience and that of their comrades is not forgotten by others. The written remarks of the ex-POWs demonstrate that their ritual of remembering former comrades is not one that other visitors can fully participate in. For the ex-POWs, the other visitors can mainly learn from their stories and experiences. Comments in the Changi Murals visitors' books indicate a distance that ex-POWs feel towards other visitors to the site. They see themselves as elder teachers communicating to younger generations a story, which they are reluctant to discuss in detail for some reason. Walter Mariner, an ex-POW of the Australian 8th Division, illustrated this divide between the ex-POWs and the other visitors when he wrote in note form during June 1991, "Preservation of Murals and the story of origins Essential for future generations [sic]."

{12} The paradox of ex-POWs being reticent about their experiences but still insisting that the younger generations of visitors should learn from their stories has been noted by observers of pilgrimages by war veterans. Hank Nelson, an historian with a group of Australian ex-POWs visiting historic POW sites in Southeast Asia, commented that, on return visits, "the ex-prisoners regret intensely their inability to communicate the greatness that some of their comrades expressed in their dying". Perhaps, he speculated, the reasons for the reluctance of the ex-POWs to reveal their stories on these pilgrimages have been due to an awareness that talking about the acts of heroic selflessness of their former comrades also means discussing frankly and publicly the "behaviour of the minority who died in squalor, scheming, abusing and stealing".10

{13} Few ex-POWs have been prepared to make any such admission in the large number of published memoirs and oral history interviews. The paradox is present most vividly in one of the best-selling POW books, Russell Braddon's 1952 memoirs The Naked Island. Humphrey McQueen, an historian, has noted that Braddon's "repeated assertions that his fellow prisoners were beyond reproach are denied by numerous anecdotes of selfishness and callous bastardry".11 At Changi camp, for example, guards had to be posted to stop hungry and desperate men from stealing crops ready for harvesting. Even the guard commander of Changi's coconut plantation was caught stealing coconuts. John Coast, in one of the earliest and well-known POW memoirs, admitted that he and his fellow officers regularly stole coconuts during the night to alleviate their hunger.12 Despite an awareness of the range of behaviour the prisoners exhibited, many ex-POWs still see the enduring value of their experience as expressed in the heroic selflessness that ordinary individuals displayed and the feeling of a shared sense of humanity that equally ordinary people felt.13

Impressions of tourists and relatives of ex-POWs visiting the Changi Murals

{14} The tourists and relatives of the ex-POWs visiting the Changi Murals appear to readily accept that this "lesson" in heroic selflessness is the key message they "learn" through understanding the POW experience. However, they are less aware than the ex-POWs of the range of human behaviour exhibited in captivity, from the selflessness of those who laid down their lives for their comrades to the selfishness of those whose actions contributed to the miseries of other POWs. The tourists and relatives see the POW experience in black and white terms, with the POWs as "innocents" or "saints" and all their Japanese captors as being stereotypically "bad", "evil" or "cruel". Having absorbed at the sacred site of the Changi Murals what they perceive as the meaning of the POW experience, the comments made by the tourists and relatives display greater emotion - and indeed naivety - than those made by the ex-POWs. They tend to be overwhelmed by the beauty of the murals and the messages conveyed by them. In August 1995, Naziram, a Muslim visitor from Singapore, wrote that viewing the Changi Murals "brings tears to my eyes".

{15} Perhaps this strong emotional response comes from conflating the sufferings of Christ with the sufferings of the POWs, which is to some extent implied in the murals. A number of tourists and relatives of POWs have expressed thoughts indicating that they believe the paintings of the sufferings of Christ are a metaphor for the sufferings of the POWs. In January 1987, Joy Hale, an English tourist, wrote in the visitors' book, "God bless Stanley Warren for his remarkable generosity evident in his work, particularly 'Father forgive them for they know not what they do'." In March 1988, Susan Soh, another visitor from Singapore, also drew this comparison when she wrote of her "absolute admiration of the endurance, courage and the pain of suffering which attests the lives of innocents".

{16} Tourists have identified the sufferings of the POWs closely with the sufferings of Jesus and the Apostles. In the minds of impressionable children the POWs have appeared as saints, or as being "anointed" somehow by God so that they are "instruments of his will". A Singapore school girl from Yung An Primary School wrote in August 1996, "Stanley you relived [sic] the memory of their suffering during a time of indescribable hardship. All of you achieved a lot. You are true saints. Bless you. Praise the Lord. Peace on Earth." Another student from Singapore Chinese Girls School wrote in September 1997, "the work of God is amazing!!! And always will be." Audrey Marchant from England in March 1988 stated her belief that the POWs were instruments of God's will when she wrote of Stanley Warren that "an invisible hand guided his brush so all may see". The POWs are viewed by relatives and tourists as Christ-like not only in their suffering but in their forgiveness of their captors. In June 1992, Victor Charlton Barnes, from England, wrote in the visitors' book that his visit was "in memory of my father Capt Arthur Charlton of the 16th Punjab and of all those who suffered too. He lived till June 1982. He forgave those who made them suffer."

{17} The relatives of POWs often feel that they personally are representing their loved one and his story of suffering amongst what they see as the suffering of all POWs at the hands the Japanese. In November 1987, Dorothy Todman wrote, "Peace and blessing to all the souls of the Japanese Prisoners of war who suffered so terribly at the hands of their captors and did not live to see the green fields of England once again." She ended her comment with the information that her brother had been "murdered in Death March 1945, North Borneo - no known grave." In March 1988, Frank and Kate Howard from England described how their pilgrimage was "a promise kept to Henry Strolt, a former POW". Linda Seute, from England, wrote in February 1994 that "this visit is for the best dad a daughter ever had, mine, Alf Butler, who was a prisoner in Roberts Barrack 1942." In January 1997, Kay and Derek Mower, from England, "signed for Uncle George and all those that suffered here."

[18] The relatives of ex-POWs have written that they use the site of the Changi Murals to recall the memory of their loved ones. For them, as well as the ex-POWs, it is a place for remembering. The site connects them with the past of their relative. Wendy Brown, from Australia, wrote in July 1995, "thank you for preserving something that helps us remember our grandfather's sacrifices". Again in September 1996 Julia and Dan Edwards from New Zealand made a similar comment, "thanks to the Singapore army for preserving this history for making it available for all to see, especially for those whose relatives were imprisoned in this place".

{19} Most visitors to the Changi Murals, whether ex-POWs, their relatives or tourists appear to see themselves as participating in some kind of pilgrimage. Visitors to the site have sometimes just written the word "pilgrimage" next to their name. Even foreign tourists such as B.S. Marwa, a visitor in June 1994 from Calcutta, have written that the "visit was my homage to those who stayed in the prison". Lloyd has offered the same description of travel in the interwar years to the battlefield sites of the First World War. He observed that for veterans, relatives of the fallen, and even the tourists, "the language of pilgrimage dominated the way in which battlefield travel was described and imagined".14 Ex-POWs, their relatives and tourists, as John Urry has suggested, seem to have the same gaze upon the sacred site, although they come to the Changi Murals site with different perspectives.

{20} If at times the ex-POWs, their relatives and tourists are engaged in a kind of communion in jointly remembering the war dead, especially during religious services held at the site, at other times social boundaries between the different groups, and within groups (such as the ex-POWs), do not dissolve into social communion. This is evident in the large number of dedications by the ex-POWs to a former comrade rather than to POWs in general. Perhaps they are mindful that not all of the POWs were selfless, and wish to remember only those that they had favourable impressions of, rather than all. However, both the relatives and tourists imbibe a common message of POW suffering at the site that appears to be so overwhelming that common bonding, or what Victor Turner has called "communitas", probably is experienced by most visitors.15 Even the writings of members of the families who say they are visiting on behalf of an ex-POW relative are similar to the comments of the tourists. Both groups indicate that they are emotionally engaged by what they see in the murals - the common suffering of the POWs.

{21} Despite periods of communitas or common bonding at the site, there still exists a definite status difference between the relatives of ex-POWs as well as the tourists on the one hand, and ex-POWs on the other. The social boundaries do not seem to permanently break down into a lasting feeling of bonding among equals as Turner's notion of communitas suggests. Each participant in the rituals at the Changi Murals is conscious of a personal definition of their own status. Ex-POWs believe they have a message to impart and assume roles as elder teachers. Relatives and tourists believe that they have something of considerable value to be learned, and see themselves almost as students. There appears to be an interplay of times when visitors experience communitas and other times when they are conscious of their different opinions and discourses. Recent work on pilgrimages by Bonnie Wheeler has suggested that what occurs at a pilgrimage site may well be a situation in which "communitas and conflict are constantly being negotiated" through "sustained interplay", which she has called "confluence".16 The idea of confluence gives greater depth to Urry's observation that there is coalescence between the gaze of the pilgrim and that of the tourist. The record of experiences of the visitors at the Changi Murals does seem to add weight to Wheeler's notion of confluence.

Restoring the Changi Murals for pilgrimages

{22} Lloyd in his work on pilgrimage sites after the First World War has remarked that the evocative nature of the sites was crucial in creating the aura of "sacredness". He observed that "the nature of the battlefield itself could make the traveller a pilgrim".17 The atmosphere of the site of the Changi Murals, which has historically evoked the emotional responses from the ex-POWs, relatives of the fallen, and the tourists, has been a product of a long process of recreation of the historic war site. This process has been shaped by the demands of both pilgrims and tourists. The history of the war site resembles the processes that Lloyd has described in his account of how the First World War battlefields of France became "hallowed" ground for groups of pilgrims and tourists. Often the efforts of military personnel and promoters of tourism coalesced to recreate the past at the historic war sites.

{23} The restoration of the Changi Murals began in 1963, as an attempt by the commanders of British forces in Singapore to create an army base identity that incorporated the wartime past of the area.18 The pre-war Changi Army Base, which the Japanese used to house POWs, had reverted back to military use in 1946, with the army occupying Selerang Barracks and the Royal Air Force taking over Roberts Barracks. The murals were still visible on the walls of the former POW hospital chapel, which became a billet for RAF airmen. Many ex-POWs were still serving at Changi after the Second World War, mixing with younger members of the armed forces who had no direct experience of the British military past in Singapore. Senior officers believed that there should be a common identity for the two groups. According to Helen Weir, a local artist who was asked to restore the paintings which were deteriorating badly after twenty years, it was the "C.O. [Group Captain McLean] of the station whose idea it was to preserve and restore the Murals, and to bring to that room an altar used by prisoners of war, and photographs taken when Changi was a P.O.W. camp, and keep it all as a memorial".19

{24} Over the Christmas holidays of 1963, Warren was brought out from England to restore the murals at the expense of Changi military base. For him, the trip was a pilgrimage. The mixed feelings he had about returning when he was contacted by Group Captain McLean were described in an interview during his second trip back to Singapore in 1982:

I didn't immediately want to come. I felt that there would be some sort of. trauma. I didn't know. I had so much hesitation. I thought I am trying to forget this. I had tried so hard immediately after the war. I mean my wife had to wake me up, you know, with terrible nightmares in which you were running away, of being pursued. It went on for years. You never really recovered, you know. It took years really to eliminate the memories and the fears. It's very easy I think to have an action like physical battle, and if you survive its over. But the long drawn out experience and really waiting for death over three and a half years. It's an awfully long time to wait to expect death. And I really tried to forget. I wanted to dissociate myself in a way. But of course, I was never able to do that.20

{25} Warren also said in 1982 that he was prompted to come back the first time by a sense of "duty", arising from his belief that he owed his life to having been assigned to paint the murals. In 1943 the Japanese had called on senior British officers at the Changi camp to assign men to be sent "somewhere up country" to do labouring work on what turned out to be the Burma-Thailand Railway. Warren - who was then critically ill with renal disease - was kept behind by his commanding officer, Colonel Roberts, who felt that his work on the murals was valuable for improving morale. Because of his frailty, Warren was convinced that he would not have survived the horrendous conditions on the railway. He said in 1982, "Certainly I would have died without the Chapel." His reservations about returning to Changi were overcome by a sense of obligation that he should preserve the memory of his comrades who did not survive. Restoring the murals was repaying "a debt for the life that I have lived since".21

{26} Working with personnel at the Changi base, Warren transformed the murals into a pilgrimage site for both ex-POWs and younger serving members of the armed forces. He was able to restore the three murals that were left more or less intact - the Resurrected Christ, Last Supper and Crucifixion scenes (even though the last-named had a doorway going through its lower half). At the time, however, it was believed that both the Nativity and St Luke in Imprisonment murals had been destroyed; the wall they were on appeared to have been knocked down by the Japanese, and then later rebuilt. Warren still had his drafts for the Nativity, so he was able to recreate this one mural on a board that was attached to the wall where it used to be. An albatross was placed prominently by Warren in the repainted Nativity scene, representing the Changi air squadron that had helped him restore the murals.22

{27} The inclusion of the albatross symbolised the incorporation of Changi's POW past into the identity of the new military base. There were other signs of this process. In 1965, a book simply called a History of Changi was commissioned for the personnel on the base. Written by RAF Squadron Leader Henry Probert, it aimed to foster an emotional connection between the younger airmen who had arrived in the postwar period and the older ex-POWs. Probert conducted extensive interviews with ex-POWs and used documents supplied by them about the site. He wove this material into a narrative that also traced the postwar history of Changi as a centre for the RAF.23

{28} After Warren's departure, RAF personnel at Changi considered themselves the custodians of the murals and their story. In 1966 a pamphlet for visitors to the site was published by base authorities which told the story of the murals in evocative terms and created an aura of the sacred around them. This pamphlet was undoubtedly based on what Warren told personnel at the base. It recounted how Warren, as a very sick hospital patient, was inspired to start painting the murals when during "his convalescence he heard the sound of Australian voices singing Merbecke's arrangement of the Litany". In "great pain and discomfort [and] weakened by his experiences, [he] was strengthened and indeed restored by the sound of the voices of his comrades raised in faith and praise". The pamphlet suggested that after hearing the ecclesiastical music, "he resolved to employ his artistic talent to create a symbol of his faith and gratitude".24 This aura of sacredness had been absent in the 1950s, when the airmen billeted in the barracks - being unaware of the history of the place - saw the murals as oddities.25

{29} The publications put out by the Changi military base fashioned a story for visitors that accorded with the base's senior officers' own concerns about the message that the murals should convey. This illustrates David Lowenthal's point that recreating history is not a value-free endeavour to reproduce an objective past. Recreating the past is more often done for a set of interests dictated by contemporary concerns. Heritage projects are generally history constructed for the present. This is not necessarily what the past was like.26 The Changi Murals were seen as part of the military heritage of the British armed forces. The pamphlet given out to visitors from 1966 to 1971 emphasised the sacred nature of the room containing the murals, but it also contained the moral that new arrivals to the base had been told since the 1940s: that the murals represented "the triumph of good over evil".

{30} James Lowe, a young airman who arrived at Changi base with other junior servicemen in December 1948, recalled that within a few weeks of arriving, "we were told the wartime history of the same [the base] and never to forget the terrible happenings there, we were then shown the Murals, by which I was really moved".27 The 1966 pamphlet used the same phrases as those heard by fresh arrivals to the base, such as Lowe:

The Murals, now restored are visited by many who come to Changi. Some see them and recapture the grim days of the occupation when they were themselves prisoners at Changi. Others see them as a reminder of the faith and courage, which overcame evil and enabled them to survive it. For all who take the opportunity to see the Murals there is one enduring message of the victory of the powers of light over those of darkness.28

The Changi military base's narrative of the past did not accurately represent the history of the murals, but gave its own interpretation of how they were created. From the historical evidence, it is clear that Warren created the murals to illustrate a common sense of humanity shared by all, including the Japanese. He had not developed the murals along the theme of the triumph of good over evil.

{31} From 1948 to 1966, during the time of the Malayan Emergency and Indonesian Confrontation, the military base was under tight security and there were very few civilian visitors.29 However, airmen billeted in the room that contained the murals report regular visits during the 1950s by military personnel who were ex-POWs.30 After 1966, when the security restrictions were lifted, more ex-POWs came back on pilgrimages. By the late 1960s there was such a steady stream of visitors that the base detailed staff to take care of them and pass on the reconstructed story of the murals. In January 1969, Squadron Leader J.M. Carder (the Senior Education Officer at the military base, who was allocated the task of showing visitors the murals) reported to Warren in a letter that the murals were "now one of the sights of Singapore and are seen by all VIPs to the station as well as by ordinary visitors". Carder particularly commented on "the ex POW particularly from Australia, who make something of a pilgrimage to Changi".31 It was, however, not only the growing number of ex-POWs who viewed their visits as pilgrimages, but also personnel from the postwar Changi military base.

{32} Attempts to make the POW past of the Changi Murals part of the identity of military personnel stationed at the military base in the postwar period proved effective. After it was announced in January 1968 that the British would withdraw their forces from Singapore by early 1971, personnel at the Changi base began lobbying for the murals to be transferred back to Britain with them. In October 1968, Charles Morris, a British Labour Member of Parliament (MP) and an ex-serviceman, wrote to Denis Healey, the Minister of Defence in the Wilson Labour Government, to "find out what, if any plans have been made by the ministry and the Government of Singapore for the preservation of the Murals when the RAF who now occupy Changi finally withdraw". He asked Healey "to consider the possibility of transferring the Murals to Britain". Morris told the British press that "it would be a tragedy if they were lost", because "apart from their religious significance and artistic merit they are an example of the creative will of British servicemen in times of great suffering".32

{33} In the House of Commons during December 1968, Healey was asked by two other concerned MPs what plans were there "to ensure that the Changi Murals in our base in Singapore will be preserved, and the buildings maintained and made readily accessible to visitors, particularly ex-Service personnel, after the withdrawal from the Singapore base". Healey replied that he had "arranged for a full study to be made of the best method of preserving these Murals, if this can reasonably be done, and of maintaining access to them by interested members of the British public".33 Removal back to Britain was the first option examined by Healey's study. However, after tests were done on whether the murals could be physically moved without damaging them, only the Nativity Mural (on wallboard) was taken when the British military pulled out of Singapore.34

{34} The attachment to the Changi Murals of former RAF personnel stationed at the base persisted over decades. Many of them returned to Singapore to visit the murals, describing their visits as pilgrimages. One of the largest groups of postwar ex-servicemen involved fifty former Changi RAF personnel and their wives, who revisited in January 1998.35 This group comprised members of the British ex-servicemen's group, the RAF Changi Association, which was formed in 1996. The members of this organisation still view the Changi Murals as a part of their group identity, decades after completing their postings in Singapore.36

Re-creating the Changi Murals for tourism

{35} After the British left Singapore in 1971, the Changi military base was occupied by the Singapore Armed Forces, which became the new custodian of the murals. However, the increasing number of visitors to the site soon attracted the attention of Singapore's tourism authorities, who intervened to re-create the place for tourism. In the 1980s several officials of the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (STPB) were interested in promoting the Changi Murals as a tourist spot. The location was already attracting hundreds of international tourists a week, because it was on the same tour as a visit to Changi Prison.37

[36] Stanley Warren was given a free trip to Singapore in July 1982 by the STPB to publicise the Changi Murals. He was also asked to paint a new copy of the Nativity Mural, since the removal by British military authorities of his 1963 wallboard re-creation of this scene had left a barren place on the wall of the former POW chapel. To commemorate the fortieth anniversary of the fall of Singapore, Warren exhibited a number of his paintings at the Sentosa Wax Museum (on the Singapore theme park island, Sentosa) which featured wax figures of the British and Japanese leaders at the surrender on 15 February 1942.38

Nativity mural after restoration.

{37} On his 1982 return visit, Warren expressed reservations that there may be a contradiction between re-creating the Changi Murals for tourism and their role as a site of pilgrimage:

I am a little worried that they should be thought of in terms solely as a tourist attraction. Of course it's important the tourists come. I mean obviously, they make that contribution to Singapore's economy, but I would like as many people in Singapore as possible to know and regard them as part of their history. The most tragic period in Singapore's history. thousands died through forced labour, deliberate brutality or famine, non-nutrition, and untreatable diseases.39

Nonetheless, by the time of his next visit in 1988 Warren was actively engaged in working with the STPB to re-create the former chapel housing the Changi Murals.

{38} In June 1988 the STPB announced that it "was taking steps to re-create the Chapel as it was so that visitors can appreciate the Murals in a setting as close to the original as possible". This activity was part of an overall tourist attraction strategy aimed at the increased numbers of international visitors that could be expected during the forthcoming fiftieth anniversaries of the events of the Second World War. Tourism officials hoped that these public commemorations would generate valuable publicity for various tourist attractions in Singapore. A spokesperson for the STPB announced that restoring the Murals "is part of the Board's efforts to weave a common theme, 'the Battle for Singapore', through several historically important attractions. Already a replica of one of the other Chapels within Changi Prison has been re-created just outside the prison grounds."40

{39} In May 1988, Warren was taken back to Singapore for a British ITV television documentary program being made on life in Changi during the war, The Human Factor - Return to Changi. STPB officials were quick to add their hospitality to ITV's, by paying for him to extend his stay by two weeks. They hoped Warren would help promote the tourist attractions that they were re-creating around the theme of the fall of Singapore. Warren worked with his ex-POW friend, Wally Hammond, to re-create St Luke's Chapel as it was in 1942. Hammond described how it was expected that "in due course, the altar and altar rail, lectern, credence table, and seating should reappear, looking, we hope, as near as possible to the original". He and Warren had no doubt that the "original objective was to create an area of tourist attraction", but their STPB Divisional Director, Mrs Pamelia Lee, said that "in so doing they have inevitably created a memorial to the people who lived and worked there during the occupation, and are very happy to have achieved this result."41 Presumably this is how Hammond and Warren reconciled making the Changi Murals both a site for pilrimage and a tourist attraction.

Restored altar.

{40} The 1988 re-creation of the Changi Murals site effectively marked the handing over of the place to the tourist authorities of Singapore. In May that year Warren, at the request of STPB officials, signed over to the Board whatever copyright he had over the use of the murals that he had created at Changi.42 The handover was symbolised by Wally Hammond giving Pamelia Lee the Toc H Changi Lamp on 23 May 1988 to be placed at the site of the Changi Murals. Toc H was a movement formed during the First World War and which consisted of Christian soldiers who volunteered to spend most of their time providing "sustenance" and "spiritual reassurance" for the sick and wounded. At Changi there were eleven groups of Toc H, including one at St Luke's Chapel under the guidance of Padre Chambers. The "Changi Lamp of Maintenance" presented to the STPB by Hammond was hand-carved by the POWs during the war. According to Hammond, the lamp "when lit symbolises the spirit of light which its members should show amongst all people, that they may see good work being done, and glorify 'Our Father who is in Heaven'." The Toc H Changi Lamp had been sent back to Britain in 1968 to be a memorial to Padre Chambers, who died while a POW. The lamp was returned to Chambers' old parish in the Southampton area. Hammond said in Singapore in 1988 that "its Padres now feel that its rightful place is in Changi, where it belongs, and symbolises the good work done here."43

{41} Warren and Hammond willingly handed over what they felt was their "custody" of the Changi Murals to the Singapore tourism officials. Warren had said in 1982, when restoring the Murals, that he felt he would not be around in twenty years time to restore them again because of his age.44 He died in 1992, and Hammond passed away in 1995. In their last touch-up of the Changi Murals, Warren and Hammond had set out proposals on how to preserve the Murals. These involved considerable expense, such as sealing the Murals behind airtight clear polycarbonate screens, which would be opened up for regular inspections. Other recommendations went against the interests of tourism, such as restricting flashlight photography.45 In the 1990s none of these recommendations were followed up.

{42} The tourism officials responsible for helping Warren to re-create the Changi Murals did, however, keep the commitments they had made to him. Despite requests in the late 1990s from officials in the Ministry of Defence to move the Changi Murals from the Singapore Armed Forces Base to a more convenient location, Pamelia Lee (who was also a member of Singapore's National Heritage Board) affirmed that these "would not be removed, as it is the STB's [the Singapore Tourism Board] intention to keep heritage pieces intact and in their original location for as long as possible".46 Oddly, by the 1990s, the individuals most interested in maintaining the Changi Murals as an historic site were the Singapore tourism officials who had helped Warren restore the Murals in the 1980s. It would appear that they understood that tourists visiting the Murals are attracted by the prospect of approaching the site as if they were pilgrims. To remove the Murals would thus destroy their value as heritage items and as a tourist attraction.

{43} The restoration of the Changi Murals in the fifty years following the end of the Second World War illustrates several significant points that have been made by various authors on re-creation of the past for tourism and pilgrimage. The Changi Murals confirm Lloyd's idea that regardless of whether a visit is made by war veterans, relatives of the fallen, or tourists, the language of pilgrimage dominates their encounters with the sacred war site. In Urry's words, the visitors experience a similar gaze upon the sacred object. The murals, like many historic war sites, have been deliberately reconstructed to evoke the emotion and language of pilgrimage. Thus, Lowenthal's remarks about how re-created sites are reconstructed according to contemporary concerns are borne out by the history of the Changi Murals.

© Dr Kevin Blackburn

The author

Dr Kevin Blackburn is Lecturer in History, Humanities and Social Studies Education at the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Since his arrival in Singapore he has become aware of the deep spiritual meaning that the place holds for visitors from Australia and elsewhere, often hearing them declare an intention of visiting Changi as a "sort of pilgrimage". He has published various articles on remembering the fall of Singapore and the Japanese occupation.

Notes

1 David W. Lloyd, Battlefield tourism: pilgrimage and the commemoration of the Great War in Great Britain, Australia and Canada, 1919-1939 (Oxford: Berg, 1998), pp.13-48.

2 John Urry, The tourist gaze: leisure and travel in contemporary societies, (London: Sage, 1990), pp.10-12.

3 Lloyd, Battlefield tourism, pp.7, 218.

4 For illustrations and information about the basic layout of the area in which the Changi Murals are located there is a section dealing with it on the Singapore government's public information and education website,http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_918_2004-12-15.html

5 Rachel Barnes, "The Story behind ... The Changi Murals", Straits Times, 17 July 1982, Section 2, p.1.

6 Stanley Warren to Helen Weir, 1963, Stanley Warren Collection, NA 1189 (National Archives of Singapore).

7 Stanley Warren, Reel 2, Oral History Interviews, A000205/08 (National Archives of Singapore).

8 Lloyd, Battlefield tourism, pp.13-49.

9 Jay Winter, Sites of memory, sites of mourning: the Great War in European cultural history (Cambridge University Press, 1995), p.52.

10 Hank Nelson, "Travelling in Memories: Australian prisoners of the Japanese, forty years after the fall of Singapore", Journal of the Australian War Memorial, 3 (1983), pp.23-24. See also Gavan McCormack and Hank Nelson (eds), The Burma-Thailand railway (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1993), pp.152-153.

11 Humphrey McQueen, Japan to the rescue (Melbourne: William Heinemann, 1991), p.300.

12 John Coast, Railroad of death (London: Commodore Press, 1946), p.15 and p.20.

13 Nelson, p.23.

14 Lloyd, Battlefield tourism, p.34.

15 Victor and Edith Turner, Image and pilgrimage in Christian culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978), p.13.

16 Bonnie Wheeler, "Models of pilgrimage: from communitas to confluence", Journal of Ritual Studies, 13:2 (1999), p.28.

17 Lloyd, Battlefield tourism, p.25.

18 H.A. Probert, History of Changi, (Singapore: Prison Industries, 1965), p.3.

19 Helen Weir to Stanley Warren, 1963, Stanley Warren Collection, NA 1189 (National Archives of Singapore).

20 Stanley Warren, Reel 2, Oral History Interviews, A000205/08 (National Archives of Singapore).

21 Stanley Warren, Reel 2, Oral History Interviews, A000205/08 (National Archives of Singapore).

22 Stanley Warren to J.M. Carder, 12 January 1969, Stanley Warren Collection, NA 1189 (National Archives of Singapore).

23 Letter From H.A. Probert, Henley on Thames, (stationed at Changi 1963-65) 14 October 1997.

24 The Changi Murals (Singapore: Kok Wah Press, 1966?) - a copy sent in correspondence with John Gimblett, a guide to the Changi Murals for the Church of England in Singapore at Changi military base (1967 to 1970), 14 August 1999.

25 Correspondence with former airmen billeted in Roberts Barracks Block 151. Letters from B.P. Northover, Upminister, Essex, England, 23 October 1997 (billeted 1951) and Roger Higinbottom, Wirral Merseyside, England, 2 April 1998 (billeted 1956 to 1957).

26 David Lowenthal, The past is a foreign country (Cambridge University Press, 1985).

27 Letter from James Lowe, Lumb Rossendale, England, 31 March 1998 (billeted 1948 to 1949).

28 The Changi Murals.

29 Letter from H.A. Probert, Henley on Thames, 14 October 1997.

30 Letter from Roger Higinbottom, Wirral Merseyside, England, 2 April 1998 (billeted 1956 to 1957).

31 J.M. Carder to Stanley Warren, 2 January 1969, Stanley Warren Collection, NA 1189 (National Archives of Singapore).

32 "In Captivity.", Daily Mirror, 23 October 1968, p.13.

33 Buchanan, Howie, and Healey, House of Commons, Vol.775, 11 December 1968, pp.149-150.

34 See Wally Hammond, The Story of St. Luke's Chapel Changi, Singapore and the Stanley Warren Murals, typed script, 1995, (Military Heritage Branch, Ministry of Defence, Singapore), p.7, and J.M. Carder to Stanley Warren, 2 January 1969, Stanley Warren Collection, NA 1189 (National Archives of Singapore).

35 S. Tsering Bhalla, "Briton wants ashes scattered in Changi", Straits Times, 30 January 1998, p.25.

36 Letter from Russ Wickson, Archivist and Newsletter Editor of the RAF Changi Association, 2 February 1998.

37 Robertson E. Collins Project Report 8 March 1987 A Plan to Re-Design the Changi Prison Stop on the East Coast Tours, 57, PD/PRJ/45/87, vol.1, Changi Chapel and Museum and Changi Prison; and East Coast Tour, 67, PD/PRJ/45/88, vol.7, Battle for Singapore, Changi Chapel and Museum in (MFL AJ024), Singapore Tourist Promotion Board Records (National Archives of Singapore); and Kevin Blackburn, "Commodifying and commemorating the prisoner of war experience in Southeast Asia: the creation of Changi Prison Museum", Journal of the Australian War Memorial (2000) No. 33 /journal/

38 "Painter of Changi Murals here for exhibition", Straits Times, 12 July 1982, p.9.

39 Stanley Warren, Reel 2, Oral History Interviews, A000205/08 (National Archives of Singapore).

40 Singapore's Changi Murals Restored by Original Artist, Overseas Press Release, 2/6/88, 69, PD/PRJ/57/88, vol.1, Battle for Singapore, Changi Murals in (MFL AJ024), Singapore Tourist Promotion Board Records (National Archives of Singapore).

41 Toc H Returns to Changi, written by Wally Hammond, June 1988, in 70, PD/PRJ/57/88, vol.2, Battle for Singapore, Changi Murals in (MFL AJ024), Singapore Tourist Promotion Board Records (National Archives of Singapore).

42 Memorandum dated 26 May 1988, in 69, PD/PRJ/57/88, vol.1, Battle for Singapore, Changi Murals in (MFL AJ024), Singapore Tourist Promotion Board Records (National Archives of Singapore).

43 Changi Lamp, and "Historic TOC H Lamp Comes to The Soton", Southern Evening Echo 29 October 1968, p.16, in 69, PD/PRJ/57/88, vol.1, Battle for Singapore, Changi Murals in (MFL AJ024), Singapore Tourist Promotion Board Records (National Archives of Singapore).

44 Stanley Warren, Reel 2, Oral History Interviews, A000205/08 (National Archives of Singapore).

45 Changi Visit, 19.5.88: Report on the Condition of the Murals, in 69, PD/PRJ/57/88, vol.1, Battle for Singapore, Changi Murals in (MFL AJ024), Singapore Tourist Promotion Board Records (National Archives of Singapore)

46 "New home for prison chapel museum", Straits Times, 27 September 1999, p.33, and personal communications with various officials in the Singapore Tourism Board, Ministry of Defence, and Singapore National Archives in August-October 1997.