Remembered. The Dernancourt Cross

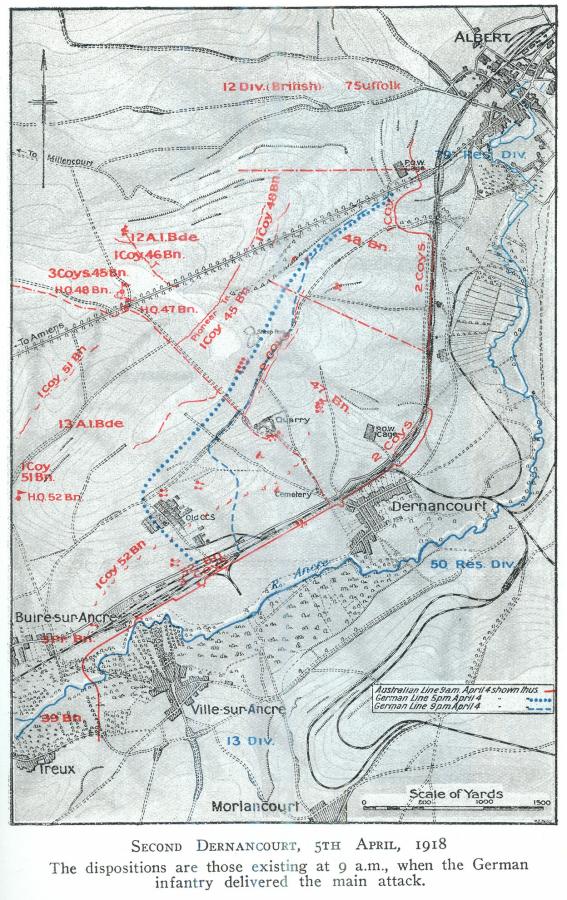

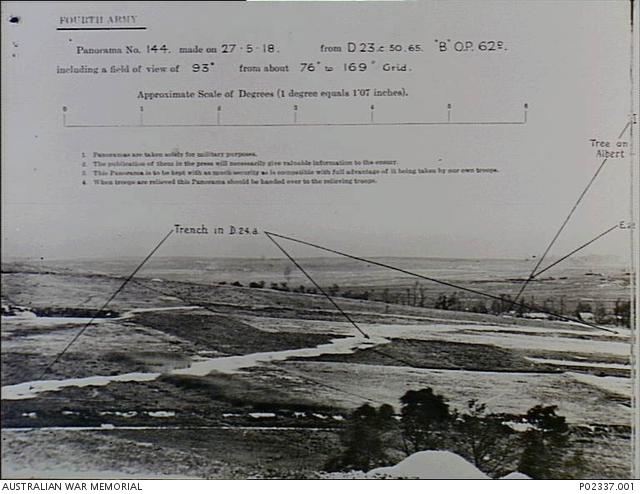

It is the spring of 1918 and the great German offensive, Operation Michael, is driving westward. The morning of 5 April is misty with poor visibilty. At 6:55am, the men of the 12th and 13th Brigades of the 4th Division are in their forward positions along the railway embankment as the German artillery barrage starts to fall. Behind the Australians is a long rising bare slope at the top of which is the Amiens – Albert road. In front of them on the other side of the railway embankment is the village of Dernancourt. In and beyond the village are three and a half divisions of the German army. At 9:25am, after two hours of constant artillery bombardment, the Germans attack.

Dernancourt is a vital battle. Both sides know it. A German breakthrough in this part of the line will leave the road to Amiens open. This will allow the enemy to drive a wedge between the French and British Armies and possibly capture the strategically vital city of Amiens.

The main German attack crashes into the Australian positions on the railway embankment. The fighting is fierce and at times without mercy - shooting, stabbing, kicking hand-to-hand fights to the death as the Australians try to hold the thin line. The German Storm troopers battle their way through and around pockets of the defenders and continue to advance up the slope. Lieutenant George Mitchell MC DCM of the 48th Battalion wrote later that the roar of battle was so loud that men could not hear the sound of their own rifles and knew that they had fired only because of the recoil of the weapon.

The fighting is desperate. Men fire as they withdraw up the slope, many die where they fight. Others are isolated and captured. Such is the effectiveness of the German attack that a machine gun battery positioned at the quarry – halfway up the slope - is surrounded and captured before it can fire a shot.

The Official History, tells how “when the seven survivors [from a 47th Battalion position] in his part of the support trench were surrounded after a very hard fight and surrendered, they were asked by a German officer who they were. On Private F Curtis … saying ‘’ Australians”, the officer drew his pistol and shot Curtis through the stomach. Curtis dropped, and the officer told two others of the group to carry him to the rear, where he died.’

Throughout the day the Australians struggle to stem the seemingly overwhelming German tide; it is a fighting withdrawal - trying to fill gaps, maintain contact with nearby positions, keeping men together and avoiding being over-run or surrounded. All the while, shooting down an enemy that keeps coming.

As the attackers near the top of the hill, every available man is called upon. Individuals, components of units, Engineers, Pioneers – all are thrown into a final defence. At 5:30pm a fierce counter attack by the 49th Battalion hits the Germans with what Lieutenant Mitchell described as ‘irresistible momentum”. This attack halts the German advance, forces the enemy partially down the slope and establishes a new front line that traces itself diagonally across the slope facing Dernancourt. The Australians have lost ground, but the front has held and the road to Amiens is secure. Here the line remains until the German withdrawal in August 1918.

It is here then, all those months later that, near positions once defended by the 48th Battalion, the graves of two Australians are found near several of those of German dead. Written in German on the crosses over the Australians’ graves is, 'Hier Liegt Ein Tapferer Englischer Krieger' (Here lies a brave English warrior). This cross is now held in the collection of the Australian War Memorial.

In a battlefield setting, burying the dead is first and foremost a basic practicality. That their enemies have buried these two Australians is not extraordinary or even notable, but that in doing so they choose to honour them for their bravery is particularly poignant. The closeness to German graves suggests the intimacy of the fight and it is not unreasonable to suppose that the German soldiers who buried their comrades also buried and chose to honour the men responsible for their deaths.

In 1953, Charles Bean, First World War war correspondent, author of the Official Histories and at that time chairman of the Australian War Memorial board, described this cross as ”one of the most valuable relics in the Memorial.” His respect for the Dernancourt cross was reflected in his proposal a year later that it be put on display in the Memorial’s Hall of Memory – the place he envisaged for the future interment of an Unknown Australian Soldier.

The First World War consumed its participants at an industrial rate. Modern technology in the form of artillery and machine guns, tore, rent and obliterated men so efficiently that, of the more than 60,000 Australians who were killed in that conflict, about 18,000 – almost one in three - have no known grave. The nature of this war meant that the same few square miles of ground might be fought for many times over. As a result, areas could be turned over so thoroughly that battlefield graves and their contents often vanished forever.

To those left to grieve in Australia, the cemeteries of the Western Front must have seemed as remote as the moon. The thought of a respectfully tended grave may have provided some comfort, just as the words, ‘missing’ and ‘no known grave’ held added pain and emptiness. In response, war memorials sprang up in even the smallest communities across Australia providing a focus for remembrance and mourning.

These two young Australians - mourned by their family and friends and with their names since engraved in memorials in France and Australia - remain today ‘Known unto God’. At the time of their deaths in the spring of 1918 however, they were honoured as Charles Bean wrote, by “a tribute [that] comes from the most important source – the men against whom the Australians…were fighting.” The Dernancourt cross remains a lasting and fitting memorial.