Out in the Cold: Australia's involvement in the Korean War - War in the air: the Royal Australian Air Force in Korea

“I wasn't new to operational command nor to the ground attack role except this war in Korea was a very different, and very ugly, war.”

Wing Commander Dick Cresswell, 77 Squadron, RAAF

Film of Meteor jets being loaded with bombs, Australian pilots flying Meteors in formation.C190650

RAAF units in the Korean War

- 91 Composite Wing

- 77 Fighter Squadron (flying P-51 Mustang and later Meteor aircraft)

- 30 Communications Unit (later known as 30 Transport Squadron, 36 Transport Squadron, flying Dakota aircraft)

- 391 Base Squadron

- 491 Maintenance Squadron

Just a week into the Korean War, airmen of 77 Squadron, who had been stationed in Japan with the British Commonwealth Occupying Force (BCOF), were flying ground-attack missions and bomber escorts from Iwakuni, Japan.

Soon the squadron moved from Japan to a succession of bases in Korea as the UN forces advanced and then retreated - Taegu, Pohang, Hamhung (North Korea), Pusan and Kimpo. The squadron was praised for its skill and courage during thousands of flights made during the war.

After the success of the Inchon landing, the air force provided crucial support in relieving some of the pressure on ground troops. Pilots from 77 Squadron ranged far and wide over the Korean peninsula, providing cover for the advancing US Eight Army as well as making their own attacks on North Korean forces. Many bombing attacks severely disrupted the progress of enemy ground forces. The main targets for air attack included North Korean railway lines, roads, military installations and vehicles. Initially pilots were equipped with propeller-driven P-51 Mustang fighters used during the Second World War; their weapons were bombs, rockets, machine-guns and napalm.

Members of 77 Squadron RAAF assembled in front of their Mustang aircraft, Iwakuni, Japan, 1950.

Pilots of 77 Squadron, RAAF: from the left: Eric Douglas, Bill Mitchelson, Tom Murphy, Bill Horsman, Ken McLeod, Les Reading, and Lou Spence (Commanding Officer) gather around the tailplane of Spence's Mustang aircraft, Taegu, Korea 1950.

Although the combined UN forces' airpower was superior to North Korea's, the entry of the Chinese into the war made the situation in the air more complicated. They too had airpower, and to the dismay of the UN forces, superior aircraft - MiG-15 jet fighters. In response, 77 Squadron had to switch from flying Mustangs to Meteor jets.

Chinese ground forces were more skilled than the North Korean forces in avoiding the damage caused by UN airpower. They were more mobile, better camouflaged, better able to cross large distances quickly, and were less reliant on supply networks, scrounging for food and other supplies as they travelled.

The death of 77 Squadron's commanding officer, Wing Commander Lou Spence, just over two months into the war on 9 September 1950, sent a shock through the squadron. His aircraft crashed during a ground attack over Angang-ni. Spence was replaced by Wing Commander Dick Cresswell.

On 1 December 1951, fourteen Meteor jets of 77 Squadron were attacked by some fifty MiG-15s high over North Korea. At least one MiG was shot down, the first victory by a Meteor, but three Australian pilots were downed. One of the three was Sergeant Vance Drummond, who landed in enemy territory south-east of Pyongyang and was taken prisoner (POW).

In 1952, UN strategy shifted to "air pressure" - an attempt to force the Chinese into battle and defeat them. The improvement of the Chinese and North Korean anti-aircraft weapons increased the danger of this campaign. In the final stages of the war, the strategy of air pressure concentrated on the destruction of ground targets - an area where UN airpower continued to be successful.

At times the weather was just as hazardous to pilots as flying under attack. Taking off was difficult in winter: thick ice and snow had to be removed each morning from the aircraft. In the event of ditching in the sea, pilots' immersion suits gave them only a few minutes to be rescued before the freezing water temperature would kill them. The heat of summer created problems as well: sometimes bitumen would melt onto the underside of aircraft during take-off and landing. The humid summer haze extended into the atmosphere up to 1,000 metres, cutting visibility to less than three kilometres.

The pilots of 77 Squadron flew almost 19,000 individual sorties while in Korea. Their performance also reaped diplomatic rewards: their excellent reputation played a large role in the signing of the ANZUS pact. Yet despite their successes, during three years of operations 77 Squadron paid a high price. Forty pilots were killed - 30 killed in action, eight in accidents, and two in accidents on the ground. Six were captured and became POWs. Of the squadron's 90 Meteors, 54 were lost during the war.

Oxygen mask for high altitude, and throat microphone, worn by 77 Squadron pilots.

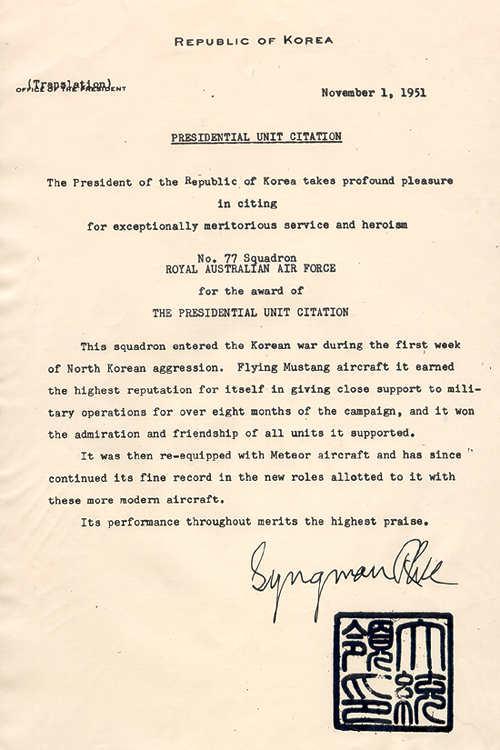

The Presidential Unit Citation from Syngmann Rhee, President of the Republic of Korea, awarded to 77 Squadron in November 1951. 114 665/7/6