Stolen Years: Australian prisoners of war - Prisoners of war in Korea

“Podos”

Thirty Australian servicemen were captured by North Korean or Chinese forces in the Korean War, 1950–53.

Five men endured captivity for over two years. Flight Lieutenant Gordon Harvey was the first Australian captured, in January 1951; Corporal Don Buck, Private Tom Hollis, Private Robert Parker, and Private Keith Gwyther were captured in the first half of 1951. They endured long years of brutal treatment for their “uncooperative” attitude.

Prisoners in Korea suffered many of the same trials as those of the Japanese – neglect, hunger and brutality – but in the biting cold of a Korean winter. They also endured attacks on their minds. In a war fought between rival ideologies, “brainwashing” was used to try to turn prisoners from the cause they served.

Propaganda photo of prisoners of war eating apples in a camp at Pyoktong, c. 1952. Warrant Officer Ronald Guthrie of No. 77 Squadron, RAAF, is on the left.

Aftermath

Captivity leaves its marks, on the bodies and minds of those who survive, and on their families. Liberation, eagerly anticipated, brought its own challenges: rebuilding lives and fulfilling dreams.

Those who lost loved ones continued to mourn, thinking of the years of family life taken from them. Those who returned continue to reflect on the years captivity stole; their individual memories evoke a range of emotions.

Some resist traumatic or unpleasant thoughts; others think of the positive – of the comradeship that eased the ordeal. Some dwell in bitterness; others have been able to think of the experience with acceptance.

While these stolen years can never be reclaimed, their legacy of endurance, comradeship and sacrifice remains.

An Australian prisoner of war, shortly after release from “Bicycle Camp” on Java, September 1945. He managed to keep the accordion throughout captivity, despite orders to the contrary.

Borneo Burlesque

Like many other prisoners, the men at Kuching in Borneo wrote and staged plays for diversion and to sustain morale. After the war the ex-prisoners would attend group reunions and re-stage their war time productions. Borneo Burlesque, a limited edition book was published, with one copy for each man; it reproduced all of the surviving posters and drawings for the plays, as well as portraits of many of the men.

Private John Bell was one of the prisoners, and his son, Robert, recalls how precious the book was in his family: it would rarely be opened, usually only when he asked his father about the performances and the camp, and then only by his father. Robert recalls attending the reunions in Perth as a child but not comprehending their significance. It was not until he became an adult that he really understood the importance of the lifelong bonds formed by the prisoners’ common experience.

Jock Britz and Don Johnston

Second World War enlisted Australian Imperial Force

Lieutenant M. (Morrie) Brennan

pencil with charcoal on paper

drawn in Kuching, Borneo, in 1944

acquired in 1978

Jock Britz

Second World War enlisted Australian Imperial Force

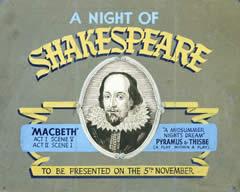

A night of Shakespeare

collage, gouache with brush and ink over pencil on blue paper

drawn in Kuching, Borneo, in 1944

acquired in 1978

Jock Britz and Don Johnston

Second World War enlisted Australian Imperial Force

Lieutenant John Morrison

pencil with charcoal on paper

drawn in Kuching, Borneo, in 1944

acquired in 1978

Jock Britz and Don Johnston

Second World War enlisted Australian Imperial Force

Sinbad the sailor

gouache with brush and ink over pencil

drawn in Kuching, Borneo, in 1944

acquired in 1978

Jan O’Herne

“Fifty years of silence”

In March 1942 Jan O’Herne, a 19-year-old Dutch woman, was interned with her family in Japanese-occupied Java. Two years later, she and nine other young women were forced into a Japanese army brothel. For four months, these women were repeatedly raped by Japanese army officers. O’Herne always resisted and was often beaten. She survived the brutal assaults, but, traumatised, could not speak about her experience.

O’Herne married, had children, and with her family migrated to Australia, always living with the memory of her terrible ordeal. Finally, in 1992 in Tokyo, together with other former “comfort women”, O’Herne bravely spoke out about Japanese wartime atrocities.

Ray Parkin

A tribute from one prisoner to another

In Ray Parkin’s art one prisoner pays tribute to another.

Parkin was a petty officer on HMAS Perth when the ship was sunk in the Sunda Strait. He spent time in Changi, on the Burma–Thailand Railway, and in Japan.

On the railway Parkin made many secret drawings and notes on scraps of paper, which he kept hidden. His subjects were the lush scenery of the jungle, rather than the surrounding squalor and misery. He met the Australian surgeon Edward “Weary” Dunlop. When Parkin was to be moved to Japan, Dunlop volunteered to hide the drawings, which he returned after the war.

Later, in gratitude for Dunlop’s gallantry and integrity during captivity, and in dedication to returned prisoners, Parkin began to remake the little sketches in drypoint, a printmaking technique. In 1956 he gave the prints to Dunlop in a handmade album.

Ray Parkin

Second World War enlisted Royal Australian Navy

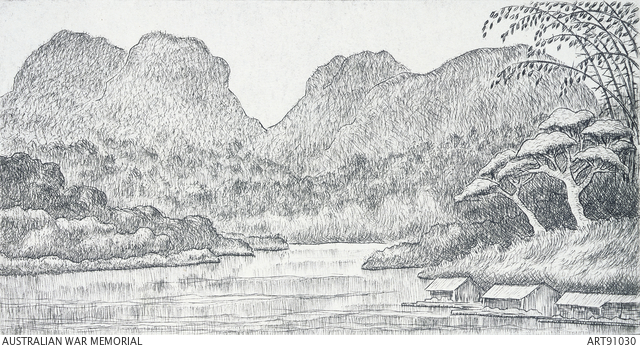

Return to River Kwai

drypoint on paper

made in Melbourne in 1992

acquired in 1999

Parkin made a single special print each year about his prisoner-of-war experience, which he would send to Dunlop at Christmas. He sent this, the last of these little prints, in 1993, the year Dunlop died.

Ray Parkin

Second World War enlisted Royal Australian Navy

Ghosts! Weary Dunlop’s clinic

drypoint on paper

made in Melbourne in 1993

acquired in 1999