Awaiting Armistice: A Prisoner of War’s Return from Korea

The Korean Armistice Agreement, signed 70 years ago on 27 July 1953 by military commanders from the United Nations Command, the Korean People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army, ended three years of intense conflict. This also began the process of demobilisation and the return of prisoners of war from Korean camps, including Australian Flying Officer Ronald David Guthrie.

United Nations guards outside the building at Panmunjom, in which the armistice was signed

Approximately 18,000 Australian service personnel had served during the Korean War. In the course of the conflict, hundreds of Australians lost their lives, with over a thousand wounded and 30 becoming prisoners of war. Guthrie was one of the prisoners of war who lived to make the journey home, but not before experiencing a series of extraordinary trials.

Guthrie was captured on 29 August 1951 after making a narrow escape parachuting from a felled plane. In a 2001 oral history recording with the Australian War Memorial he recalled his descent into a rice paddy: “But the last ten thousand feet [three kilometres] went past very rapidly, and the last two or three thousand feet [600–900 metres], I could hear this - snap! snap! snap! [sound] – going past. I didn't wake up what it was for a while until I looked up and I saw holes in the parachute canopy, and I realised that somebody on the ground was probably shooting at me.”

Though fortunate to have survived, his ordeal was far from over. Over the next two years Guthrie suffered gruelling conditions as he was moved between various Korean prisons, including an agonizing month in Sinuiju, “the greatest hell hole [he’d] ever seen”. He endured illness, lice infestations and strict rationing. While held in Pyongyang, he and three other prisoners of war, Jack Henderson, Tony Farrah-Hockley and Tom Harrison, enacted a daring escape plan. Over two nights they cut a hole in the wall, propping Harrison (who only had one leg) against it during the day to hide the evidence. Henderson, Farrah-Hockley and Guthrie snuck out on the second night, only to be recaptured days later while trying to traverse a minefield. Guthrie was forced to walk approximately 300 kilometres in freezing conditions to the Pinchon-ni prison camp, where he remained until being released through the Welcome Gate to Freedom at Munsan-ni. He was released on 3 September 1953, just over a month after the armistice was signed.

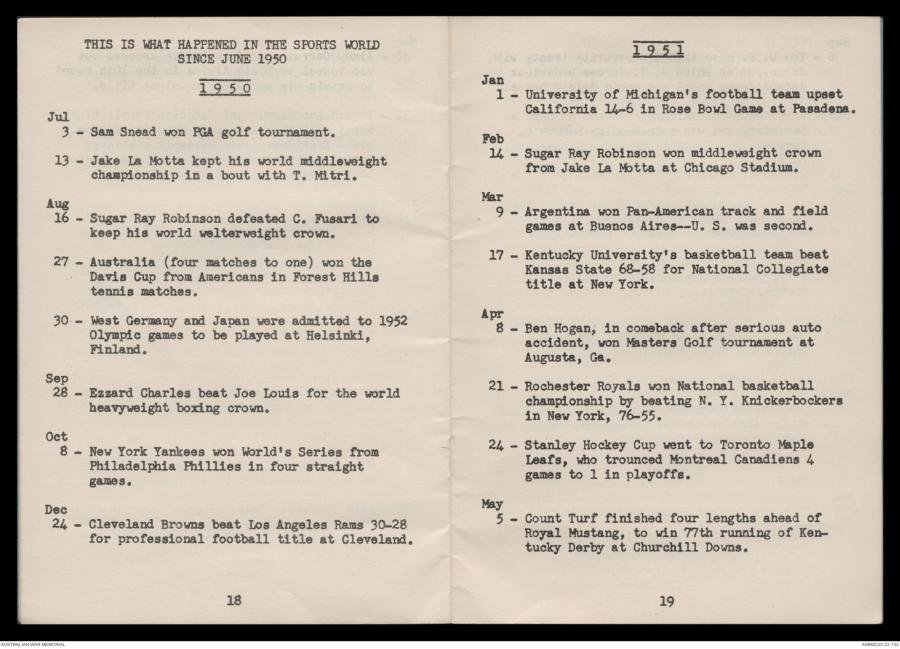

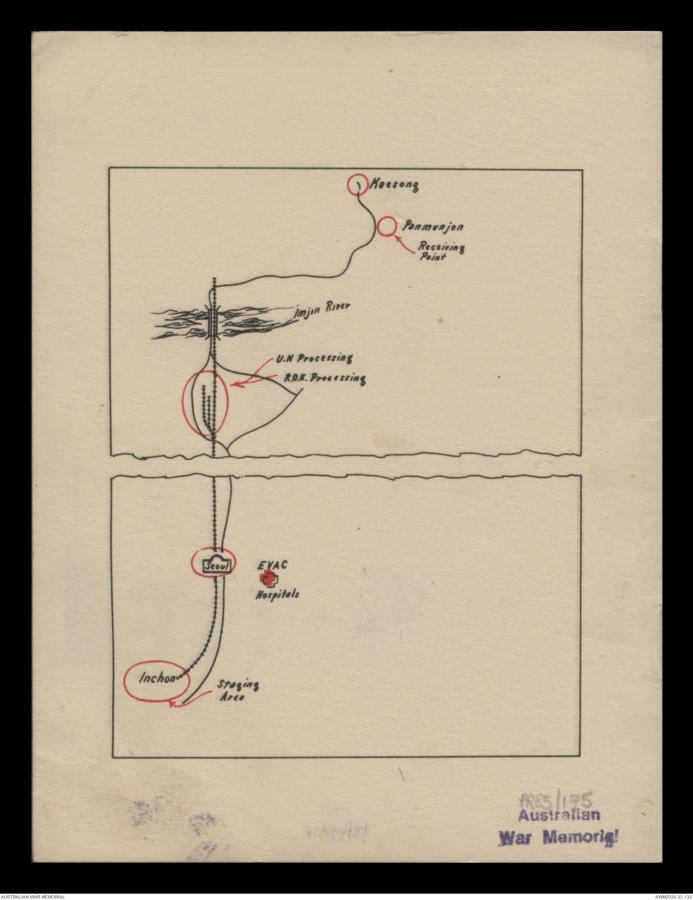

Prisoners of war passing through Munsan-ni were presented with information packs to prepare them for repatriation. Amongst Guthrie’s papers held at the Memorial are two booklets he received before returning home, one giving a timeline of major events from 1950–1953, the other outlining the procedure for release through Panmunjom, including a map of processing facilities.

List of major sporting events in 1950 and 1951. AWM2020.22.132

8th US Army Welcomes Home United Nations Personnel. AWM2020.22.132

Map of processing facilities. AWM2020.22.132

It’s difficult to imagine what it would have felt like for those prisoners of war to arrive back on Australian soil after months or years of internment. Guthrie recalled, “But when I stepped off that aircraft at Mascot, on September 13 … 1953, my mother and father were there at the airport … and that was heaven blessed as far as I was concerned.” For Guthrie, the armistice meant more than an end to the fighting, it was a path to reunite with loved ones; it was homecoming.

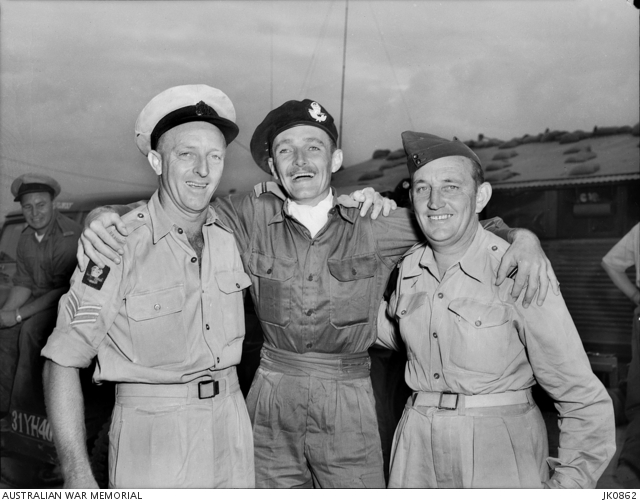

RAAF pilots arrive at Camp Britannia after their release from prisoner of war camps in North Korea. Left to right: Sergeant John William Mackintosh, Flying Officer Ronald David Guthrie and Flight Lieutenant Jack Gorman.