'An inspiration to us all'

Warning: this article contains images of deceased persons.

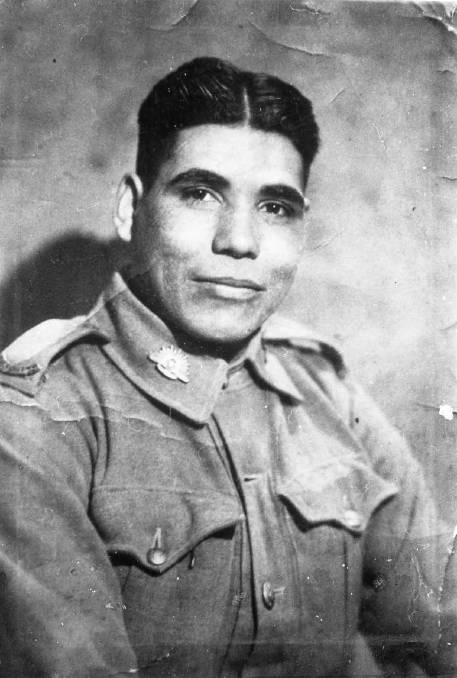

Private Frank Richard Archibald. Photo: Courtesy the Archibald family

Private Frank Richard Archibald was 27 years old when he was shot and killed by a sniper’s bullet during the Second World War.

He was trying to save his mate when they were attacked by a group of Japanese in the swampland around Sanananda, following the fighting on the Kokoda Trail.

His mates were devastated by his loss. In a letter written to Frank’s mother shortly after his death, a senior sergeant, Ron Diamond, wrote: “I can honestly say Frank was one of the most popular boys in the battalion and his cheery disposition and ready smile, even in the darkest hours, made him an inspiration to us all.”

Known to everyone as “Dickie” or “Dick”, Frank Richard Archibald was born in Walcha, New South Wales, in February 1915. The son of Frank and Sarah Archibald, he was the eldest son of 13 children and the elected successor of the Gumbaynggirr peoples, whose lands stretch along the Pacific coast from the Nambucca River in the south to around the Clarence River in the north and the Great Dividing Range in the west.

When the Second World War broke out, Frank and his younger brother Ronald were determined to do their bit, fighting for Country – the term used by Aboriginal peoples to describe the lands, waterways and seas to which they are connected, and which expresses complex ideas about law, place, custom, language, spiritual belief, cultural practice, material sustenance, family and identity.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a long-standing tradition of fighting for Country.

Despite laws that prevented and discouraged them from enlisting, Indigenous Australians have served in every conflict and commitment involving Australian defence contingents since Federation.

Frank was one of thousands of Indigenous Australians who enlisted for service during the Second World War, doing so at Kempsey in May 1940. His younger brother Ronnie, and his uncle Richard, would also enlist.

By the time Frank arrived in New Guinea, he had already served with the 2/2nd Battalion in the Middle East, Greece and Crete. He took part in the attacks to capture Bardia and Tobruk in early 1941, and was later in a group of 12 which became cut off during the evacuation of Greece; the group made its way to the coast and obtained a fishing boat to escape to Crete.

In New Guinea, Frank and his brother Ronnie fought in some of the worst conditions along the Kokoda Trail.

His battalion fought major engagements at Templeton’s Crossing, Oivi, and on the Sanananda Track, suffering heavy casualties in the process. Having started the campaign with almost 700 personnel, by the time the battalion fought its final actions in December 1942, it had an effective strength of less than 100, many having been evacuated due to sickness.

Franks’s brother Ronnie became ill with malaria and was evacuated, but Frank continued. In letters home to their mother, Frank noted that just surviving on the track was a struggle, let alone doing battle with Japanese forces. He also noted how he used his bush skills to help fellow soldiers collect drinking water.

Portrait of Australian soldiers, many of them members of the 2/2 Battalion, taken at Greta Camp, prior to embarkation for the Middle East. Private Frank Richard Archibald is pictured, second row, fourth from the left.

On 24 November 1942, the 2/2nd Battalion was in the process of securing Sanananda when it encountered a group of Japanese soldiers dug in along the track. Under intense fire, the commander made the decision to split the platoon, leaving a group to engage the enemy while the rest of the platoon moved forward. Frank was engaging the enemy when he noticed a friend caught in a dangerous position. He was trying to save his friend when he was shot and killed.

Back home in Australia, Frank’s sister Hazel was about to have a baby. Before he died, Frank had written to his mother, asking her to tell his sister that if she had a son, to name him Richard, after him. She named her child Richard Stanley Owen.

Frank was buried near where he fell, but his remains were later reinterred in the Bomana War Cemetery near Port Moresby.

On Anzac Day 2012, members of Frank’s family, including his sister Grace, gathered at the cemetery to call his spirit home in a traditional spiritual ceremony conducted in the Gumbaynggirr language.

Frank's cousin, Uncle Richard Archibald, told reporters that he felt responsible for ensuring that the only family member not buried in Australia found his way back home.

“Now it is time to end the grieving by bringing his spirit home to Gumbaynggirr country – the country of our people,” he said.

Uncle Richard Archibald, above right, works tirelessly to raise awareness about Indigenous servicemen and servicewomen. "This was their Country … and they wanted to fight for their Country."

A proud Gumbaynggirr man, Uncle Richard Archibald was the first Aboriginal person to carry out a ceremony for fallen Aboriginal diggers so that their spirits could be returned to country.

Soil from Frank’s home country was placed at his gravesite during the ceremony, and soil from the gravesite was brought back to Australia to be reinterred with his family in Armidale Cemetery.

The group visited the graves of five other Indigenous soldiers buried in Papua New Guinea, with instructions from their families detailing how they would like them to be honoured.

“I knew about them, and about my father, because he was in the war too,” Uncle Richard said.

“They were all up at Walcha … up near Armidale… The welfare was going to put them all in homes, and then they said if they didn’t move down to Kempsey on to the Burnt Bridge Mission they’d take all of the children off them …

“There were 13 of them… and that’s where they joined up … at the Easter Showgrounds … at Kempsey … my father and the two boys.

“Dad put his age down to go and look after his two nephews … but Ronnie, he ran away down to Sydney and joined up there because he was too young.

“They wouldn’t let him join up in Kempsey so he went down to Sydney and put his age up and joined up there.

“He was fighting for his own Country; he wasn’t fighting for nobody else, and it gave everybody else a chance to get off the missions.

“This was their Country … and they wanted to fight for their Country.

“They’d come back from the [Middle East] … straight into that … then they had to go up and into New Guinea … It’s all rainforest up there, and they had to pull everything up by rope, and that’s what I don’t understand about it now. When you go up to Papua New Guinea now to walk the Owen Stanley Ranges you’ve got to do three months training [to prepare for it]. How do you think those soldiers done it with a big 50 pound thing on their back … walking with a gun, dodging bullets and all that?”

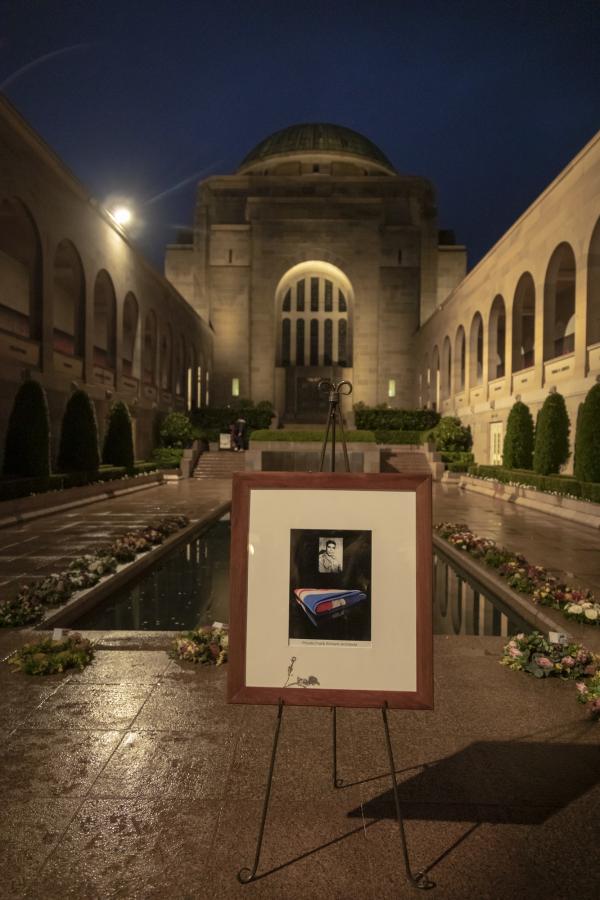

Sapper Nariah Vale at the Last Post Ceremony commemorating Private Frank Richard Archibald. Vale's grandfather was named Richard Stanley Owen Vale in Frank's memory.

Today, Uncle Richard works tirelessly to raise the awareness of Aboriginal servicemen and ensure their stories are told.

He was proud to lay a wreath at a Last Post Ceremony commemorating Frank’s life at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra during Reconciliation Week.

“It’s very special for me,” Uncle Richard said. “But it will be special for … these people here too.

“That’s all my mob … They know about it, they’ve heard about it, but they haven’t felt it, and feeling it is different.

“And then they’ll be able to talk and … that’s what’s special for me … that they can understand, and go back and talk about it.”

Frank’s story was read by one of his descendants, Richard Stanley Owen’s grandson, Sapper Nariah Vale. A specially made didgeridoo, bearing Gumbaynggirr totems and images of Frank, his brother Ronald, and their uncle Richard, was played at the ceremony. Known as a Yidaki, the instrument was played to mark the start of the official Anzac Day service at Bomana in 2012 and was used to call the spirits home from New Guinea.

“It’s not just a didj,” Uncle Richard said.

“It’s a story, and this is their story, and … everything about it.

“It means a lot to me because of what happened to my father and what happened to the boys … not only for these fellows, but for what happened to all the Aboriginal Australians who came home.

“They put them back in the missions, and they weren’t even allowed to walk into the town, and people don’t understand that part; they glorify things, but I don’t glorify things, I talk about what happened.

Wing Commander Jonathan Lilley plays the yidaki at the Last Post Ceremony. The yidaki was played to mark the start of the official Anzac Day service at Bomana in 2012 and was used to call the spirits home from New Guinea. “It’s not just a didj,” Uncle Richard said. “It’s a story, and this is their story, and … everything about it."

“I grew up on the mission where they were, so I knew about it and I heard the stories.

“When my father got a job … because he was a returned soldier … he wasn’t allowed to come back on to the mission because he was working.

“Then they cut all the rations off because he was working, but he wasn’t allowed to come onto the mission, so how could mum get the money?

“And that’s why it was so hard for people … when they returned.

“One of the men came back … and when he came back they wouldn’t let him in the RSL … He marched [on Anzac Day], but he wasn’t allowed into the RSL.

“And the Soldiers’ Settlement? The black fellas never got it … they got put back on the mission and they couldn’t even own that piece of land because it was still run by the government.

“You think about 1960 … it wasn’t all that long ago … [and] we’re still living on the missions under the Aboriginal Protectorate.

“It’s very important [to tell these stories], especially for the children to understand and to know about … because nobody talks about it.

“This is our history … and this is the main place; this is where they’ve got their names up on the board down there.

“It’s very special for me.”