'It looks like it's started'

Photo: Courtesy Jason Nixon

Jason Nixon was 19 years old when he first went to war.

It was January 1991, and he was a signalman on board the Royal Australian Navy supply ship, HMAS Success, stationed in the Persian Gulf.

“It was January 16 or 17 and I remember it was about two o’clock in the morning,” he said.

“I was in the ship’s communication centre, and there’s an alarm that sounds when you get what’s called a flash message. It’s the highest priority message you can get, and that, in a nutshell, said, ‘The war’s started, stand by for further orders.’

“I had to take that and go and wake the captain up. I didn’t know how to respond, and so I just sort of gave him a shake, and he rolled over and said, ‘What do you want, Nicko?’

“I said, ‘You’d better read this, sir. It looks like it’s started.'"

Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein had invaded Iraq’s oil-rich neighbour Kuwait five months earlier in August 1990. The attack was widely condemned, and the UN Security Council unanimously approved a trade embargo against Saddam’s regime. Over the following months, a US-led coalition of more than 40,000 troops from 30 different countries gathered in Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf to enforce UN sanctions against Iraq as part of Operation Desert Shield.

The UN Security Council set 15 January 1991 as the deadline for an Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait. When Saddam ignored the deadline, coalition forces launched Operation Desert Storm with a series of devastating air strikes on Iraqi military targets in Kuwait and Baghdad that lasted 43 days.

On 24 February, the coalition moved ground forces against Iraqi positions in Kuwait, despite widespread fears Saddam might order the use of chemical weapons. The magnitude and decisiveness of the operation destroyed what was left of Iraq’s ability to resist. Two days later, Iraqi forces began to withdraw across the border, setting fire to more than 600 Kuwaiti oil wells and dumping millions of barrels of crude oil into the Persian Gulf. Iraqi forces were expelled from Kuwait within 100 hours of the ground assault, and a ceasefire was declared on 28 February 1991.

Gunnery practice on board HMAS Success in the Indian Ocean en route to the Persian Gulf.

Jason was one of 1,800 Australian Defence Force personnel who served during the Gulf War between August 1990 and September 1991.

He had joined the navy at 16 and was an able seaman on board Success when the Gulf War broke out.

“I was just a young fella,” he said.

“I grew up in Adelaide and I had always been interested in the water and sailing. I’d sort of lost interest in school and it was my mum who drove me down the path of joining the navy.

“It was a bit of an eye opener for me at the time. I was thrown into the melting hot pot of people of all different ages, from all different backgrounds, and I was like a rabbit in the spotlights for a while.

“I ended up spending 23 years in the navy, and I probably spent 16 years at sea. I got right up the ranks to warrant officer and here I am now running a cherry and blueberry orchard in Tasmania.”

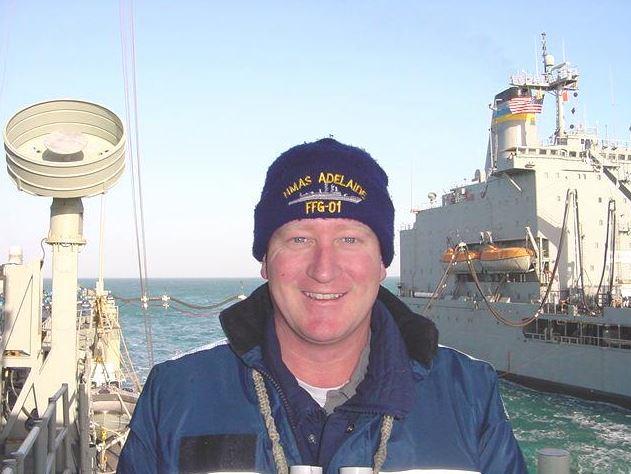

Jason Nixon served for 23 years in the Navy. Photo: Courtesy Jason Nixon

Today, Success has a special place in his heart. It was his first ship, and the one that took him to the Persian Gulf in support of Operation Damask, the Royal Australian Navy’s contribution to the war against Iraq.

He was on board Success when Prime Minister Bob Hawke announced on 10 August 1990 that three naval vessels – Success, and the frigates HMAS Darwin and Adelaide – were to join the US-led multinational force being assembled to enforce UN sanctions against Iraq and create a maritime blockade.

“We had just come back from a big exercise over in Hawai’i and we were down in Melbourne. We were just about to head to our next port when a message came through saying, ‘Make best speed for Sydney’.

“It was quite an intense period, getting the ship ready to go and doing all our training. Because they thought the threat up there was going to be a chemical threat, we had to get all our training up to speed with tackling chemical warfare and wearing biological suits.”

Success was farewelled by the Prime Minister in Sydney before sailing to the Persian Gulf with Darwin and Adelaide.

“I worked on the bridge with the command team most of the time, and worked in the communication centre, so I was privy to a lot of information that the rest of the ship’s company weren’t,” Jason said.

“I was reading the reports of the ships that were already operating in the Gulf so I had a couple of preconceived ideas of what it would be like before we arrived and they were kind of reinforced as we entered.”

HMAS Darwin, HMAS Adelaide and HMAS Success in the Indian Ocean en route to the Persian Gulf.

He remembers sailing through the Strait of Hormuz into the Persian Gulf.

“It’s a really narrow navigational entry, and you’ve got Iran on one side, and Oman and the United Arab Emirates on the other,” he said. “There were little Iranian gun boats zipping past, and the Americans were there as well, so it was a fairly tense situation, but at the time I was still fairly young and fairly naïve. I didn’t really see the politics of that at the time, but there was still a fair bit of adrenalin looking out for contacts and trying to identify threats …

“We went past a ship – Surf City – that was attacked by the Iranians in the 1980s. It’s just a rusting hulk now, but it’s quite an impressive ship. It’s a large tanker, and Success carried a lot of fuel, so when you see another ship like that that’s been attacked by missiles … seeing things like that puts things into perspective.”

Mines were another threat.

“The big thing for us was entering the Gulf,” he said. “There was an American frigate that got hit by a mine in the same water that we were in, so there was always that threat of mines so you’ve always got people out on the bow of the ship just constantly looking. After a couple of months you just get used to it, but you can’t take it for granted because that’s when things happen.”

As part of Operation Damask, Success made regular voyages to replenish coalition vessels in the Gulf, carrying 8000 tonnes of supplies during the war.

“The ship was classed as a fast combat support ship so we had the ability to go in, refuel other ships, resupply them with food, ammunition and all that sort of stuff,” he said.

“We were away for nine months, and it gets really hot up there. It’s well into the 40s, and if there’s no wind, the heat’s radiating off the ocean and the deck of the ship, and you are wearing all this gear and you are just melting.

“But after a few months, the ship found its groove.”

A crew member of HMAS Success on mine watch duty as the ship sails toward the Persian Gulf.

In November, the ship’s captain reported: “Success continues to operate like a fine clock, quietly and unobtrusively.”

For Jason, it was an interesting time. He remembers spending Christmas in the Seychelles and looking forward to the weekly mail. He could ring home once a week using a small hand-held satellite phone that “cost an absolute fortune” and was able to watch events unfold on television.

“With everything that was going on in the Gulf, everything was quite intensified,” he said.

“When we got up on the bridge [after the war started] our posture changed being in a comfortable routine to refocusing on the threats … And that’s when [Iraq] started launching scud attacks … and everything got quite intense.

“It’s hard to put into words, but you get used to it because it’s what you train for. It’s all about remaining calm when everything’s crazy around you so that you are making a good, sound decision in a difficult situation. I guess that’s how all military training is in a nutshell. Inside, the butterflies are flying, and your head is spinning a million miles an hour, but you know the procedure you’ve got to follow, and what you’ve got to say on the radios, and you just do it …

“You’ve got all these different radar feeds and satellite feeds and you’re getting information from other ships and different sources around the Gulf … It’s all in real time, so we could see enemy aircraft in the air, and see reports of missile launchers, and ships that had been hit by fire.

“But it was an interesting war because you would go up and do you eight hour watch, and then go down to the café for a brew. We had live TV on CNN so you’re sitting down having your coffee and you could see what had happened over the last 24 hours or so, so it was very surreal. We’re talking back in the days before computers and the internet, so it was very interesting when you compare it to something like Vietnam.”

Commanding officers on the deck of HMAS Success. Left to right: Captain Russell E. Shalders (HMAS Darwin), Captain WIlliam Arthur George Dovers (HMAS Adelaide) and Captain Graham V. Sloper (HMAS Success). Gulf of Oman, September 1990.

Success was relieved by HMAS Westralia and returned to Australia in March where it was greeted by thousands of people, including Bob Hawke and Governor General Bill Hayden.

“It was my home for four years,” Jason said. “That was where I cut my teeth so to speak. It’s where I learnt to do my job properly. When I got on there I was green, straight out of the box, and when I left there, I actually knew how to do my job, and had a pretty good idea of how the world worked. I guess they were my formative years and they shaped me and put me on the path to where I am today … it was such a busy ship … because of the role that Success did, we were always delivering fuel, we were always moving ammunition around, and it’s a very dangerous environment you are doing it in, but that’s the ship’s role, supporting the mission around you.”

Jason sailed to Somalia in 1993 on board HMAS Jervis Bay as part of Operation Solace, then Australia’s largest military sea-lift operation since the end of the Vietnam War.

“We were with HMAS Tobruk and we basically took the army – 1RAR and 2RAR – over there,” he said. “That was actually more scary than the Gulf. We were trying to unload their stuff, and we were getting shot at. We were only getting shot at with small weapons and things like that, but you were still getting shot at, whereas in the Gulf we had quite a bit of real estate to dodge things.”

Jason served on board HMAS Adelaide. Photo: Jason Nixon

He was serving on board HMAS Adelaide in October 2001 when it intercepted the wooden boat known as SIEV-4 about 100 nautical miles north of Christmas Island. The vessel was warned from entering Australian waters, but eventually sank while under tow to Christmas Island. The 223 passengers and crew were rescued by HMAS Adelaide. It became known as the “Children Overboard” incident.

“When you’re talking about the human element, that’s it,” Jason said. “We had these people on the top of our ship for a week and we had to feed them and look after them… You realise, they’re just like us, and it’s amazing how your perspective changes, when you see the whole picture.”

Shortly after, Jason returned to the Persian Gulf during the war in Afghanistan as part of Operation Slipper.

He retired from the Royal Australian Navy 11 years ago, but has fond memories of his time at sea.

“I spent most of my life in the navy,” he said. “It was about the camaraderie, and the team environment. You’re living in close quarters with people constantly, and if you can’t live in that environment, you’re not going to survive. It’s about trust. You know the guy next to you has got your life in his hands, and you’ve got his in yours, so it’s having that trust and teamwork, and just doing your job.”

Jason Nixon at sea. Photo: Courtesy Jason Nixon

The Australian War Memorial in Canberra is particularly special to him.

“I love it,” he said.

“Before the Gulf War, the only conflicts people really thought about were the First World War, the Second World War and Vietnam, but once you delve a bit deeper you realise we’ve been involved everywhere. We’ve had two Gulf Wars, Afghanistan, Somalia, and those of us in the military understand that because we’ve lived it. We know about these conflicts, and the peacekeeping operations that we’ve participated in, and I think it’s very important that they are recorded in some form or manner that people can access, and I think the Memorial is the best place for that because it is what it is.

Photo: Courtesy Jason Nixon

“As a veteran you appreciate the Memorial a lot more because you’ve lived it, but I think it’s good for visitors who have had no exposure at all to anything military or warlike to see what things are like … Especially when you go through the Commemorative Area and the Hall of Memory where the Tomb of the Unknown Australian soldier is, it’s a real eye opener … You can see the names on the Roll of Honour and remember the past conflicts and the soldiers …

“The Gulf War was 30 years ago now, and I was only three years into my career when it kicked off. A lot of water has passed under the bridge since then, and I’m thankful for the experiences I’ve had. As you get a bit older, you understand things a bit more, and you see the bigger picture, and that’s why I think the Memorial is such an awesome place, because you’ve got all that evidence there …

“I haven’t been for a few years now, but I’m itching to get back …You can lose yourself in there for a day.”

The Australian War Memorial’s Development Project will be sharing the stories of a new generation of Australian men and women who have served our nation in recent conflicts, and on peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. To share your story email: development@awm.gov.au

To stay informed about the Development Project sign up to the Our Next Chapter e-newsletter www.awm.gov.au/ourcontinuingstory/stayinformed