Operation Desert Storm: Thirty Years On

Wiki Commons: Kuwaiti oil wells burn following the Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait in February 1991. Photographer Sgt David McLeod, US Department of Defense, Wiki Commons.

Thirty years ago, the crews of Australian warships HMAS Brisbane and Sydney were on-station in the Persian Gulf and had ringside seats to a most awesome display of naval firepower. At 0230 on the morning of 17 January 1991, a barrage of US tomahawk cruise missiles erupted from the darkened warships of Battle Force Zulu ― the US Navy strike force that had assembled in Gulf waters ― after months of simmering tensions in the Middle East. As the missiles trailed off into the night sky, dozens of F/A-18 Hornets, F-14 Tomcats and A-6 Intruder aircraft thundered from the decks of nearby aircraft carriers to deliver devastating strikes on Iraqi military targets in Kuwait and on the Iraqi capital, Baghdad.

The Australian sailors were witnessing the start of Operation Desert Storm ― the combat phase of the Gulf War, fought between the military forces of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and a coalition force from 35 nations led by the United States. On 2 August 1990, Saddam’s troops had illegally occupied the oil-rich neighbouring country of Kuwait. Iraq had previously accused Kuwait of stealing Iraqi petroleum by tapping oil reserves under Iraqi territory, but the invasion may have been a move to avoid repaying Kuwait an enormous sum which had been lent to help finance Iraq during its war with Iran between 1980 and 1988; it may also have been a deliberate attempt to threaten the stability of oil supply from the Middle East and raising the prospect of a global oil crisis. Under a ruthless dictator who had sanctioned assassinations, executions, torture, and forced deportations, Saddam’s regime also had long history of human rights violations that included the use of chemical weapons against the Kurdish people of Northern Iraq during the genocidal Anfal campaign of the late 1980s.

These events took place towards the end of the Cold War, at a time when US and Soviet Union antagonism was thawing and the international community held greater hopes for institutions such as the United Nations to play a more significant role in solving the problems of the new free world. This renewed sense of hope was best expressed by US President George H. W. Bush who spoke of the post-Cold War period as a ‘new world order’. It was a time where ‘diverse nations [were] drawn together in a common cause to achieve the universal aspiration of mankind: peace and security, freedom and rule of law. Such is a world worthy of our struggle, and worthy of our children’s struggle.’

Gunnery practice on board HMAS Success en route to the Persian Gulf, August 1990. Photographer: Jack Picone.

Operation Desert Shield

Also faced with the prospect of a global oil crisis, the international community condemned the Iraqi invasion, and on 6 August 1990, the UN Security Council unanimously approved a trade embargo against Saddam’s regime. A naval blockade of Iraq’s access to the Persian Gulf soon followed, as the US assembled a multinational force in the Gulf and nearby Saudi Arabia as part of Operation Desert Shield, which by the end of 1990, amounted to some 40,000 troops across 35 nations. The UN Security Council set 15 January 1991 as the deadline for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait, or it would face retaliatory action from the coalition, which was authorised to use ‘all necessary means’ to liberate Kuwait.

Australia was among the 35 nations that joined the US-led coalition. In August 1990, the Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke announced ‘Australia’s total and unequivocal condemnation of the invasion by Iraq of Kuwait and its subsequent reported annexation’. He pledged that the nation ‘will not stand idly by while any member of the international community purports to break the rules of civilised conduct in that way.’ On 10 August, Hawke told the US President that three Australian warships would contribute to the naval taskforce and help enforce economic sanctions against Iraq. They were being despatched, he told Parliament, not to serve the US alliance but ‘to protect the international rule of law which will be vital to our security however our alliances may develop in the future.’ The government was criticised by for its perceived subservience to US interests, and a number of demonstrations were held in in cities across the country protesting Australian involvement in the Gulf crisis.

Captain Russell Shalders, RAN, commanding officer HMAS Darwin, observes the interception and boarding of the Iraqi tanker MV Mutanabbi in the Gulf of Oman, c. October 1990. Photographer unknown.

Australia’s contribution to the Gulf War was primarily through the three-ship RAN task group to the Persian Gulf. The first rotation of Australian warships deployed to the Middle East as part of Operation Damask in August 1990, and consisted of the Adelaide-class guided missile frigates HMAS Adelaide (II) and Darwin (I), and the replenishment oiler HMAS Success. Arriving in the Gulf of Oman on 3 September 1990, Adelaide and Darwin were authorised to stop, board, search, and if necessary, seize vessels carrying contraband cargo to ensure effective enforcement, while Success offered a self-reliant replenishment capability to coalition vessels operating in those waters. Not knowing how Iraqi forces would respond to the sanctions or the looming UN deadline, RAN sailors were prepared to face attack from Iraqi aircraft or Scud missiles fitted with chemical and biological weapons. Later, they faced the additional threat of their warships striking free-floating contact mines that Iraqi forces had released into waters off Kuwait.

(From left) HMAS Brisbane, Adelaide, Success, Darwin and Sydney rendezvous for a handover in the Gulf of Oman, December 1990.

Photographer ABPHOT Kym Degner, image courtesy SeaPower Centre

Operation Desert Storm

The second rotation of RAN warships arrived in theatre in December 1990, with the Perth-class guided missile destroyer HMAS Brisbane (II) and the Adelaide-class guided missile frigate HMAS Sydney (IV) replacing Adelaide and Darwin in the Gulf of Oman; HMAS Success continued to provide logistical support to coalition vessels until replaced by the replenishment oiler HMAS Westralia on 26 January 1991 ― in an operational first for the ADF, Westralia’s ship’s company included seven women. On 12 January 1991, Brisbane and Sydney sailed through the Strait of Hormuz and into the Persian Gulf where they joined Battle Force Zulu to form part of the anti-aircraft screen around the carrier USS Midway. Meanwhile, Success moved into a holding area in the Southern Arabian Gulf with over coalition vessels of the combat logistics force.

Captain Chris Ritchie was the commander of HMAS Brisbane, and recalled a heightened sense of anticipation not knowing when or if Iraqi forces would act before the looming deadline:

The deadline came, the deadline passed, but nothing happened. But throughout that particular day evidence really did start to build that there was an impending allied strike, and we certainly all considered that there was the possibility of a pre-emptive Iraqi strike… By 2100 on the evening of the 16th, we knew for certain that a strike by allied forces was on. A couple of hours later the threat levels were raised in the force, and in the early hours of the 17th January, quite suddenly, the radar screens of the night sky over the Gulf blossomed with missiles and aircraft heading northwest into Iraq.

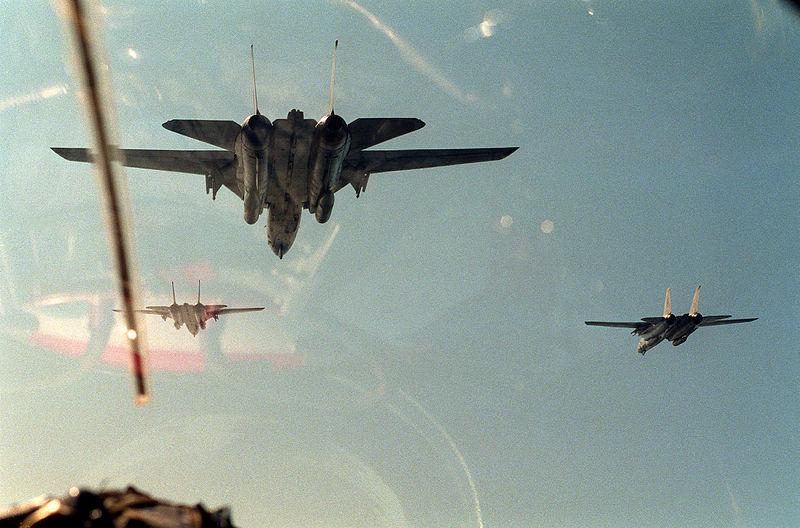

Wiki commons: US Navy F-14A Tomcats from USS Theodore Roosevelt with Battle Force Zulu, en route to support an airstrike over Iraq during Operation Desert Storm, February 1991. Photographer unknown, US Department of Defense, Wiki Commons.

So began Operation Desert Storm and the start of 42 days of consecutive air strikes against the Iraqi Air Force and Saddam’s anti-aircraft facilities, command and communication centres, Scud missile launch sites, weapons research facilities and naval forces. According to Ritchie, ‘we were elated that the allied forces were able to strike first. But clearly there was some trepidation that we’ve done it now, we are really at war. But significantly, a great cheer went up throughout the ship… and then we settled down to await the expected retaliation’.

Brisbane and Sydney continued to monitor the situation closely for an Iraqi response that never eventuated. Once this was realised, Brisbane and Sydney were redeployed to protect the naval carrier group from hostile aircraft that could emerge without warning from Iran. No threat materialised, but their additional duties went on to include combat search and rescue for downed coalition aircrew, aircraft control, and naval escort of detached high-value units.

Within a month, coalition aircraft had flown more than 100,000 sorties and dropped 88,500 tonnes of bombs ― more than was dropped on Berlin by both the RAF and USAAF combined during the Second World War. Then on 24 February 1991, coalition forces moved ground units against Iraqi positions in Kuwait and southern Iraq. The magnitude and decisiveness of these attacks destroyed what was left of Iraq’s ability to offer any form of resistance. After two days of further air strikes, Baghdad radio announced Saddam’s forces had been ordered to withdraw from Kuwait to the positions they had occupied before 2 August 1990. Implementing a scorched earth policy, they torched over 600 Kuwaiti oil wells and dumped eight million barrels of crude oil into the Persian Gulf.

Not that coalition forces permitted Iraqi forces to withdraw across the border without further action. A long convoy of Iraqi vehicles travelling along the six-lane Iraq-Kuwait highway was so extensively bombed by coalition aircraft it became known as the Highway of Death. US Marine A-6E Intruders blocked the head and the rear of the column by disabling vehicles with cluster bombs, which created an enormous traffic jam that was then assailed by coalition aircraft for the next ten hours. Elsewhere, Iraqi forces were pursued over the border and into Iraq, to within 250 kilometres of Baghdad before coalition units were recalled to the Iraq-Kuwait-Saudi border.

As soon as Iraqi forces had withdrawn from Kuwait, as sanctioned by the UN Security Council, US President George H. W. Bush declared a ceasefire on 28 February 1991 and an end to the Gulf War. Bush believed that pushing on to capture Baghdad and toppling Saddam’s regime would have fractured the coalition and sucked the US into a long and protracted struggle at great cost to the forces involved. This was precisely what happened following the invasion of Iraq by the ‘coalition of the willing’ in 2003.

A heavily rust-stained Iraqi Republican Guard chest rig, recovered by CDT3 during their explosive ordnance disposal mission in Kuwait.

Post-Conflict Operations

Australian naval operations continued until hostilities ended with the ceasefire of 28 February 1991, and for ‘sustained outstanding service in warlike operations’, both HMAS Brisbane and Sydney received Meritorious Unit Citations. Four ADF surgical teams served on board the US hospital ship USS Comfort, detachments from the Army’s 16th Air Defence Regiment deployed on board Success and Westralia, RAAF and Defence Intelligence Organisation photograph interpreters were based in Riyadh, and RAAF C-130 and Boeing 707s had flown sustainment and logistics runs between Australia and Muscat. Around 20 ADF officers and NCOs participated in ground operations during Operation Desert Storm whilst seconded to a variety of US and British units.

In response to the heightened threat of free-floating contact mines, 23 members of RAN Clearance Diving Team Three (CDT3) deployed to Kuwait in January 1991 where it was tasked with assisting explosive ordnance disposal and the reopening of Kuwaiti ports. Their work was made all the more treacherous by wartime wreckage, crude oil still flowing into the Persian Gulf and billowing smoke from the oil wells still alight. But in four months, CDT3 succeeded in clearing four ports, searching over 2 million square metres of sea bed; it also dealt with 60 sea mines, and disposed of over 230,000 pieces of ordnance. In recognition, they received a US Navy Unit Citation in 2018.

The nose cone from an Al Hussein Scud missile, which could be fitted with chemical, biological and nuclear agents. This example was recovered by Australian members of UNSCOM at the Al Muthanna chemical weapons complex near Baghdad in 1992.

Saddam remained in power, albeit under strict observation from the UN Security Council. He was reluctantly forced to accept strict UN Security Council resolutions that sought to identify and destroy Iraq’s chemical, biological and nuclear weapons capability and their associated facilities. To this end, between 1991 and 1998, around 135 Australians were involved in the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM) as part of Operation Blazer, which sought to identify, inspect and oversee the destruction of Iraq’s ‘weapons of mass destruction’. The maritime interception force would also continue to operate in the Persian Gulf and neighboring waters to prevent the sale of weapons and other material deemed forbidden by the UN Security Council. RAN warships continued to deploy to the region, with eight Australian frigates going on to serve in the Persian Gulf, Gulf of Oman and the Red Sea as part of Operation Damask between 1991 and 2001.

While the Gulf War had ended, many Iraqis still suffered from its ongoing violence and turmoil. On the day of the ceasefire, rebellions broke out in the Shia-dominated towns south of Basra and among the Kurds in Iraq’s north. They were motivated by a genuine hatred for Saddam’s Ba’athist regime, but they were also encouraged by the US President who had addressed Iraqis via the Voice of America radio service to encourage them to ‘take matters into their own hands’ and force Saddam from power. Saddam’s Republican Guard units brutally responded, employing tanks, artillery and helicopter gunships to suppress the insurrections. A humanitarian crisis then developed as thousands of Iraqis became displaced by ongoing violence.

Following a request from the US in April 1991 to contribute to a multinational humanitarian mission in Iraq’s north, the ADF sent 75 personnel to northern Iraq as part of Operation Habitat. There they helped provide medical assistance and improve the quality of life through water purification and engineering works for 15,000 Kurdish people seeking refuge in the Gir-i-Pit valley. In less than four weeks, the Australians treated over 3,000 Kurdish people, many of them children suffering diarrhoea, dehydration and malnutrition, and substantially improved water supply and preventive medicine within the camps.

Captain Jane Morris, a medical officer within the Australian service contingent that deployed to northern Iraq to provide medical assistance to Kurdish refugees. Photographer unknown, June 1991.

In all, 1,872 members of the ADF served during the Gulf War of 1990-91. There were no combat casualties among the Australian units deployed, but many veterans have suffered from their service over the following three decades. Whereas the Cold War had been the basis for Australian involvement in conflicts in southeast Asia, its end marked a shift in strategic focus to the Middle East region – defined in a broad sense to include Afghanistan, Iraq, the Persian Gulf and the North Arabian Sea. When Australian Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, announced the end of the Gulf War to Parliament on 28 February 1991, he foreshadowed an ongoing Australian involvement in the region: “We rejoice that the war has been won quickly and with so few casualties to our own forces… but the end of the war was not the end of the crisis. Much remains to be done to bring stability in the Gulf and to bring a wider, durable peace to the Middle East.” Little did Hawke realise what the scope of Australian efforts would be in the attempt to achieve this over the next thirty years.

The Australian War Memorial’s Development Project will be sharing the stories of a new generation of Australian men and women who have served our nation in recent conflicts, and on peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. To share your story email: development@awm.gov.au

To stay informed about the Development Project sign up to the Our Next Chapter e-newsletter www.awm.gov.au/ourcontinuingstory/stayinformed

Dr Aaron Pegram is a Senior Historian and Concept Developer in the Memorial’s Gallery Development Program.