'We were very lucky'

It’s just before the Last Post Ceremony at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, and 94-year-old Len McLeod is explaining how he used to lie on the floor of a C-47 Dakota, dropping essential supplies to Australian troops in New Guinea during the Second World War.

The aircraft were dubbed the “Biscuit Bombers”, and Len would lie on his back, his legs doubled up behind the load, as he waited for the aircrew to give him the ‘green light’ to kick supplies of food and ammunition out of the side of the aircraft.

“Being 6 foot tall, I was the tallest, so I always took the ground position,” he said.

“And my job … I would lay down, and hang on to the side of the plane on my back with my two feet up, waiting for that bloody green light to go on, and when the green light went on, whoosh, I’d try to push the whole lot out straight, so that it didn’t get jammed or wedged in the door.

“We’d stack up as much as we could so that it all went out, one behind the other, straight into the jungle.”

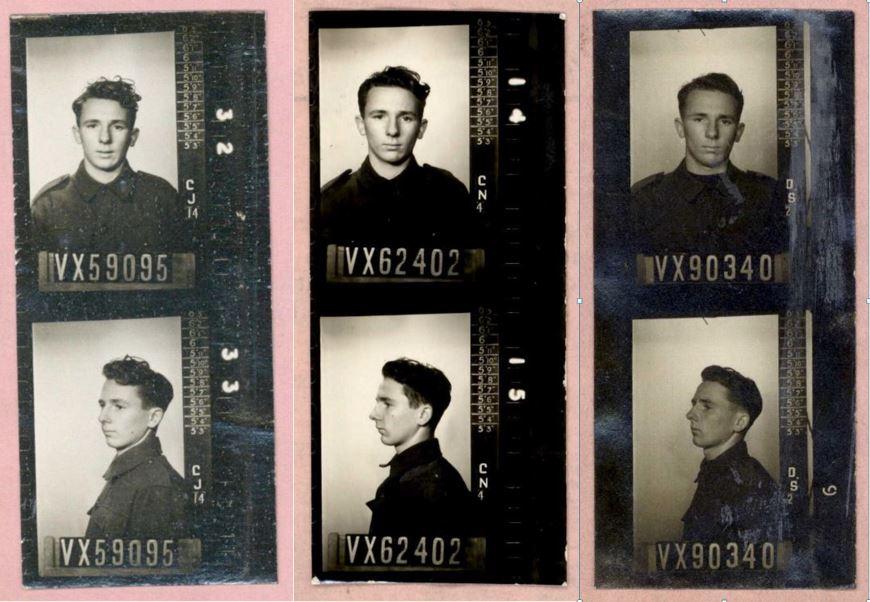

Len McLeod during the Second World War. Photo: Courtesy Len McLeod

Still a boy, Len had enlisted four times during the war; he has four different enlistment numbers, under three different names, and was just 15 years old when he first signed up to join the Australian Imperial Force.

“It was just a little bit before I turned 16, and I enlisted a few times,” he said, laughing.

“The war had broken out in 1939, and then Singapore fell, and the Japs were rushing down the coast, and into New Guinea.

“All my mates were being called up and they were all talking about it … You could volunteer for the AIF overseas or you could stay and be called up for home service, but either way you were in the army, the air force, or the navy.

“There was a group of us, and I was still 15 at the time, but all the older ones, the ones who were over 18, were all going in the army, and I found myself on my own…

“They were older than me, but I was as tall as them, so I thought I’ll see if I can go with them, so I went along with a few of them down to the recruiting office in Footscray and got in the line with them.

“I got thrown out a few times, but I kept going back with different names and one thing and another, until finally I got away.”

Len enlisted several times during the war using several different names.

The youngest child of John and Ruby McLeod, Len was born into a working class family in the western suburbs of Melbourne on 2 June 1926. His father had served on Gallipoli and the Western Front during the First World War, and his mother did not want her youngest son going off to fight in a second.

“My father’s [service] number was 35 and he was in the first lot that went to the Middle East,” Len said. “While he was in France, the Germans used the gas, and it affected him after he came home …

“I was barely five years old when my father died from the effects of being gassed, and I still remember them taking him to the hospital.”

Len lied about his age and enlisted three times before being discovered and later discharged. The fourth time he was more successful.

“Every time I went in, they would say how old are you, and I’d say 21, but they would eventually find out and throw me out,” he said.

“I left it for several weeks, and went back when a new crew had taken over, and they accepted me, but my mother found out, and she said, ‘That’s it, you’re out.’

“She rang them up after I’d joined, and had me discharged, so I got thrown out again by my own mother.”

The fourth time Len was more canny. It was September 1942, Singapore had fallen, Darwin had been bombed, and Japanese midget submarines had entered Sydney Harbour.

“I went back to the recruiting officer and they were desperate,” Len said.

“Things were getting far more serious for Australia. The country was at the point where it looked like falling … and I could see a lot of trouble ahead.

“There was a great line up at every recruiting office with people joining up… and they’d have taken anyone, I reckon … so I filled in the form, and when they said how old are you? I said 22.

“Every other time, I’d said 21, but I’d learnt my lesson, so when they asked this time, I said 22. They said go to the next table, and at the next table the doctor said stand up, put your hands above your head, up and out like that, bang, bend down touch your toes …

“And that was about it for the medical… They threw me a uniform and within two or three days I was in the camp and then onto a train up to Townsville and Canungra.”

Canungra, Queensland, 1942: Members of an Australian Infantry Unit engaged in their training course at the Jungle Warfare Training Centre.

When he left, he told his mother he was going to Queensland to serve with the Home Guard. Instead, he was going to Brisbane to be part of the first intake of Jungle Warfare Training at Canungra before sailing for New Guinea.

Still a teenager, Len didn’t even know where he was going when he boarded the troop ship bound for Port Moresby.

“We got bombed the first night I was there,” he said.

“I was only a young fellow and I could hear them all talking – ‘It’ll be on tonight, it’ll be on tonight’ – and I wondered what it was all about.

“Finally, I said to one of them, ‘What do you mean, it’ll be on tonight?’ ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘It’ll be on tonight,’ as in the Japs will bomb the s*** out of us.

“And that was the start of it …

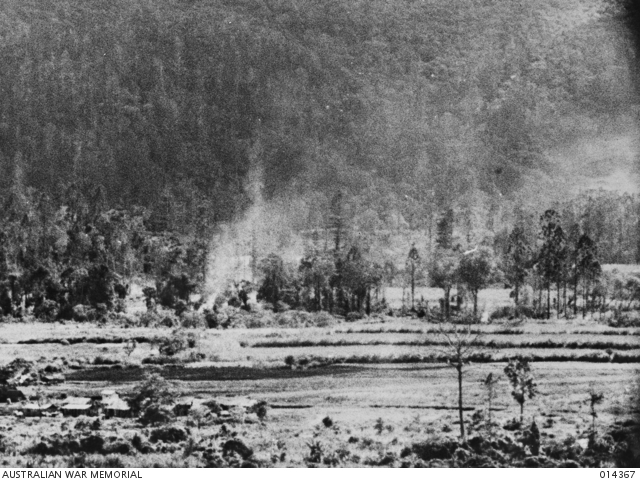

Bomb damage at Seven Mile Aerodrome near Port Moresby following a Japanese air raid.

“All around Port Moresby and New Guinea they had dug slit trenches, and they said before you go to sleep tonight in your tent, make sure you find out where your nearest slit trench is ….

“I knew what they were saying, and I knew where to go, and sure enough, that was my first introduction to bombing.

“They came over the top of us, and bombed the hell out of the airport …

“I’m in this slit trench, and I could hear the bombs dropping … and that was my first night in Port Moresby.

“The next morning they lined us all up, about five or six hundred troops just off the ship.

“They were calling for volunteers – volunteers for this and volunteers for that – and they wanted to drop three or four troops at different parts around New Guinea with a radio.

“It sounded good to me so I stepped forward, and a friend of mine, an older chap that I’d travelled all the way from Melbourne with, grabbed me by the scruff of my neck, and said, ‘Come back here you young bastard, you don’t volunteer for anything,’ and pulled me back.”

A Douglas C-47 Dakota transport aircraft engaged in a supply dropping mission.

When officers called for volunteers to serve on the “Biscuit Bombers”, Len stepped forward again.

“They were just setting up a biscuit bombing group and they wanted 18 men to volunteer,” Len said.

“They’d realised you couldn’t carry your food, and your guns, and your supplies, and a bloody big heavy rifle, and go through the jungle …

“I’d never been in a plane before in my life, and I thought this sounds alright, so I stepped forward again.

“My mate was going to pull me back again, but I said, ‘No, ‘I’ll be home every night in my bed in Port Moresby; it’s a bit better than lying out in the jungle,’ so he left me there.

“The next thing, two or three jeeps came along and I jumped in the back of a jeep … The next morning they picked us up again and we went back to the airport; the one that had been bombed the night before. It was about five o’clock in the morning and it was still dark … and they dropped us off at one of these C-47s …

“We’re standing there at this plane for five or ten minutes, and we didn’t know what was going on … then along comes another jeep … and two pilots and a radio operator jump out … and then things started to move.

“The radio operator said, ‘Have you ever dropped before?’ and I said, ‘No, no, I’ve never been in an aeroplane before,’ and he said, ‘Oh well, don’t worry, I’ll show you what to do.’

“So he took us into the plane and he showed us a red light and a green light, and said when the red light is on, don’t drop anything, and when the green light is on, kick everything out … and that was my introduction.

“The pilots get in the plane and the plane starts roaring and suddenly they take the doors off and throw them onto the ground.

“And on the DC-3s – the C-47s – there are actually two doors, a big one and a small one, and it leaves an opening of about seven feet at least …

“The next thing, they are bringing in these trucks with about two tonne of bags and they are backing them up to the back of the plane.

“Everything was put into a haversack, like a potato bag, and tied up at the top. There were four gallon drum tins of biscuits, and boxes of bully beef, and stuff like that, and [the radio operator] said put everything between the wings, just leave enough passage for the pilots to get in and out so that they can get into their seats and fly the plane.

Loading a Douglas C-47 Dakota aircraft with supplies for troops in the forward area.

“They’re firing up the plane, and we’re going down for take-off, all in a line, nine of us, one after the other.

“We had no guns, no armaments, no nothing, and the plane’s taken off without the doors. There’s a great big hole on the side of the plane, and the noise is coming in at you, so we couldn’t hear a thing.

“The plane’s going up and down, and in New Guinea, it’s all mountains, so the plane’s going up and down all the time.

“We had to go over where the wings are, and pick these boxes of bully beef up, and we didn’t feel too bloody happy about it, because out there, there’s nothing, and we weren’t tied on or anything … so it was a bit scary …

“[The radio operator] said we had to stack up as much as we could, and get out as much as we can, because if we can do it in five drops that’s terrific, but sometimes it takes seven or eight times, and we’ve got to get down to tree top level to drop.

“We could never see where we were dropping until we got up high and turned around and watched the other planes coming down because on our turn we were too busy pushing everything out.

“I found out later, the soldiers … would light a little fire on the ground, and a little bit of smoke would come up, and that was the signal for where to drop …

“Sometimes we would do two trips a day, but I always felt safe because every time we went out, we had at least six or seven or eight fighter planes somewhere around us.

“Sometimes they’d come in close to us and give us the thumbs up sign and we could see them looking out; other times they would be a mile away, but they were always there to protect us.”

He was left shaken when one of the “Biscuit Bombers” failed to return one day.

“On several occasions, we were on a dropping mission, and we were getting near the place to drop, when all of a sudden we turned around and went back to Port Moresby as quick as we could because where we were going to drop was being bombed by the Japanese.

“It was a bit scary many times, but we’d always got through; there was only one terrible incident.

“We were doing the drops one day and we lost one of our Biscuit Bombers with two chaps I had got to know very well.

“I didn’t see it go down, and didn’t even know it had gone down at first, because we were too busy getting our own supplies out, but when we were heading back to Port Morseby I could see that there was only eight planes …

“There should have been another plane to the side of me, and it wasn’t there.

“It didn’t come back, and it was a bit of a knock to me too. I knew the fellows on the plane. We’d been together when we dropped food off, and we were sort of the best of mates. And they went down with it …

“It was pretty crook, and I thought, I’ll give this dropping away.”

'Biscuit Bombers' used to carry supplies of food and ammunition to forward troops in inaccessible areas.

Knocked by the death of his mates, Len requested a transfer back to the infantry. He would go on to serve with the 2/7th Battalion at Wau and Buna before coming down with dengue fever and dysentery.

“The 6th and 7th Battalions had just arrived back from the Middle East, and they shot them straight into New Guinea and sent them into a place called Wau,” he said.

“I was only a young fellow, and I thought, ‘I’ll be in a battalion with 800 to 1,000 troops, and I’m only one of them, so my chances of dying are about one in a 1,000,’ but I found out the hard way … I was in what they call a platoon … so I was one of only 28, with a lieutenant, and a sergeant, and a corporal, and a medical officer, and that’s about all …

“They were all sunburnt and brown from being in the Middle East and here I am, snow bloody white, from Melbourne, and only a kid …

“They all looked me up and down – and these are all real crack troops from the fighting in the Middle East – and I heard them saying, ‘What’s bloody well going on in Australia; sending bloody kids up,’ but I was as tall as them, and I could fire a rifle as good if not better.

“I joined them as they were being airlifted into Wau … right in the heart of New Guinea … andwe landed just as the Japanese were attacking the airport.

“They were only 300-400 yards away, and they thought they could take it easy … but Australia controlled the airstrip, and it never fell, so we were very lucky.”

When the men of the 2/7th participated in the drive towards Salamaua, Len was still only 16.

“We followed them all the way back from Wau, and it’s a bloody long distance,” he said. “The Japs were getting reinforcements in, and our job was to sit there like spotters, and … radio back to Port Moresby … We could see them unloading … barges coming into Buna … and various other places, and as soon as [the radio operator] put the radio down, we’d have to move … because they reckoned [the Japanese] could pick up where we were.”

When Len was struck down by tropical dysentery and dengue fever, no one could be spared to go with him, so he made the two-and-a-half day trek back to Wau alone.

“All of a sudden I felt crook, and I said to the first aid bloke, I don’t feel too good mate.

“He came back with an old thermometer, and said put that in your mouth … ‘Christ,’ he said, ‘You’ve got to get back to the hospital, but I can’t release anyone to help you back. Do you think you could walk back by yourself?

"You had to sleep over night – you couldn’t do it in a day – and I was still only 16, but I said, ‘I’ll be right.’”

Near Wau, New Guinea. c.1943. Indigenous New Guinea stretcher bearers (popularly known as Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels) carry a wounded soldier from 2/7th Infantry Battalion, on a stretcher down a muddy track through the jungle to Wau.

From Wau, Len was evacuated to Port Moresby for treatment and sent to Australia to recuperate. He was shooting rabbits at home in Victoria when an army mate who was also on leave accidentally shot him in the hip and legs. More than 70 years later, Len still likes to joke about how he had survived the war in New Guinea, only to be shot by a German bullet in Keilor.

“I’ve got more lead in me now than you can poke a stick at,” he said, smiling.

“I was going to be the man who broke the four-minute mile before that happened ... but he shot me, and if you saw the X-rays you wouldn’t think that I could stand up, let alone walk. There’s something like 37 grains of German bloody shot in there, and that was the finish as far as the army was concerned; I was rats***.”

Medically discharged from the AIF, Len later marched into General Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters in Sydney and joined the Americans.