'I'd never seen anything like it'

Len McLeod was 18 years old when joined the US Army Small Ships and witnessed one of the largest naval battles in history.

“I said to the captain, ‘Where are we going? Are we going straight into bloody Tokyo or what?’ And he said, ‘To be honest, I don’t know … All they told me is we are going north.’

“And I thought, ‘Christ, even the captain doesn’t know where we’re going.’

“We ended up heading to a place called Leyte, up to a big battle … and oh, goodness, gracious, it was terrible…

“We only had two guns – a 50-calibre, which is only a machine gun, and a 20mm – and this fighter plane came over the top of us.

“The storemen who were operating the guns thought they’d damaged it, but it went straight over and straight into a ship … And later on, they found out that it was the first kamikaze.”

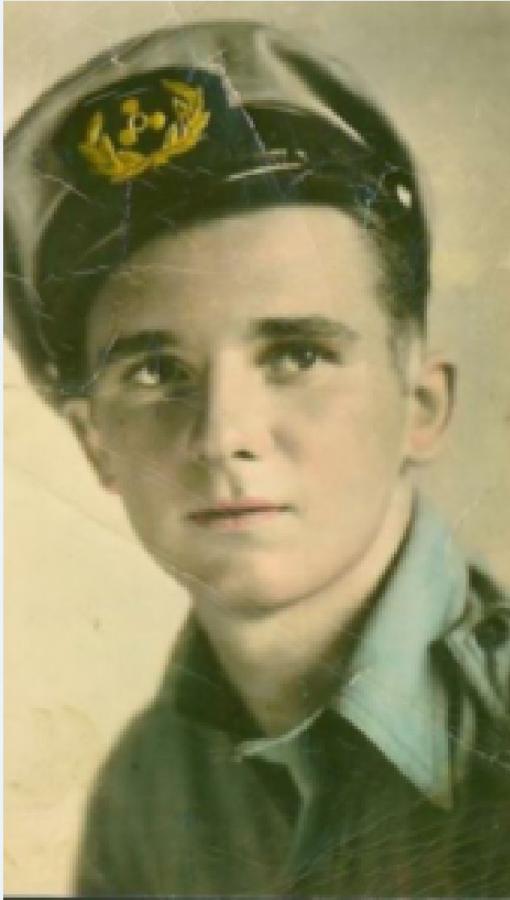

Len McLeod joined the US Army Small Ships in 1944. Photo: Courtesy Len McLeod

Len was on board the store ship, Armand Considere, and had already served in New Guinea with the Australian Imperial Force when he joined the US Army Small Ships.

Known as ‘Mission X’, and locally as the ‘rag tag fleet’, the US Army Small Ships Section was raised in Australia in mid-1942 and consisted mainly of Australians who were too old, too young, or medically unfit to serve in the Navy, Army or Air Force during the war.

By mid-1942, Allied forces were scrambling to repel the Japanese advance in New Guinea, and General Douglas Macarthur, the Commander of Allied Forces in the South-West Pacific Area, turned to an Australian fleet of fishing trawlers, paddle steamers, tugs, schooners, ferryboats, barges, sailing boats and pleasure craft to take on a critical role during the war.

Len had already served in New Guinea with the AIF when he joined the US Army Small Ships. Photo: Courtesy Len McLeod

Manned by merchant seamen, the Small Ships employed more than 3,000 Australian civilians, including one woman, during the war. They ranged in age from 15 to 80, and served alongside 1,372 US Army personnel as well as New Zealanders, Canadians, Chinese, Danes, British, Filipino, Dutch, Austrians, Torres Strait Islanders, French and one Inuit.

Some had lost an arm or a leg, or had other injuries, and had been rejected by the other armed services. Others were veterans of previous conflicts, including the Boer War and the First World War. These included Victoria Cross recipient, George Julian ‘Snowy’ Howell, a First World War flying ace, and an Austrian aristocrat who had been a German U-boat commander during the Great War.

They were responsible for delivering essential supplies to forces in the south-west Pacific, including weapons and ammunition, as well as medical supplies, food, and building materials. They were also responsible for ferrying soldiers, inserting commandos and coastwatchers, repatriating the wounded and dead, guarding and removing Japanese prisoners to holding camps, and many other logistical tasks, often sailing at night and hiding by day.

Len had already enlisted several times during the war. The first time he was only 15.

The son of a First World War veteran, Len had already enlisted four times when he joined the US Army Small Ships in 1944. He has four different enlistment numbers, under three different names, and was only 15 years old when he first signed up to join the Australian Imperial Force. He went on to serve with the “Biscuit Bombers”, dropping essential supplies to Australian troops in New Guinea, and the 2/7th Battalion at Wau and Buna, before being struck down with dengue fever and tropical dysentery. He was evacuated to Australia, and was discharged after he was accidentally shot in the hip and legs while shooting rabbits with an army mate on leave in Melbourne.

Not to be deterred, Len later marched into the Grace Hotel in Sydney and joined the Americans.

He had been looking for something to do when a mate suggested he went to work as a ‘trimmer’ on an old Yugoslav ship, SS Olga Topic. “I didn’t know what a trimmer was, but I soon found out,” he said, smiling. “It was a dirty, black job … tipping the coal from the bunkers, down the shoot, down into the fire and into the engine room … and it was filthy. You had to go in and get a barrow and cart the coal and tip it down a chute in to the engine room, and you’d get all the dust – but I didn’t mind.”

Len served with the Americans in New Guinea and the Pacific. Photo: Courtesy Len McLeod

After a few trips, a merchant seaman suggested Len should quit the “old tub” he was working on and join the Small Ships.

“He said to me, ‘What are you doing on a dirty old thing like this? Why don’t you join the American Small Ships? They give you a uniform, pay you well, feed you well. And it’s better than what you are getting here.’ So I said, ‘That sounds good. Where do I join?’”

Len jumped on a train from Newcastle to Sydney, and walked into the Small Ships office.

“This American behind the desk said, ‘Are you a merchant seaman? We want experienced seamen,’ and I said, ‘Oh yes.’

“I’d only done two or three trips to load and unload this ship, the Olga Topic, but he gave me an application to fill out.

“I read it carefully, and it said to put down the names of the last three ships you’d been on…

Len McLeod, centre, with other crew members. Photo: Courtesy Len McLeod

“I’d only been on the Olga Topic for about eight or nine weeks, but being in port, I knew the names of the other ships. So I put a bodgy one down at the top, said I’d been on that for nine months, then another bodgy one, said I’d been on that for seven months, and then the ship that I was on, the Olga Topic.

“I thought if they were going to check anything, they would only check the most recent one, and that’s what he did. He comes back in, and he says, ‘Can you leave for Townsville tomorrow?’

“I thought about it for about five minutes and said, ‘Yes.’ And I never ever went back to the Olga Topic. They probably still owe me about half a month’s money, which wasn’t bloody much in those days anyway.

“The next day, I’m leaving Newcastle, going back up to Townsville to join a ship going back to Port Moresby. And that’s how I joined.”

Len went on to serve as a fireman on the steam ship, Bopple, at Milne Bay and Finschhafen before joining the crew of the store ship, Armand Considere.

Len McLeod on board Armand Considere during the war. Photo: Courtesy Len McLeod

Len McLeod on board Armand Considere with a fellow crew member. Photo: Courtesy Len McLeod.

“I reported to an American officer there [at Milne Bay] and he said go down to the pier.

“There was an old ship that had just come in, the Bopple … and they put me on there as a fireman.

“It was a bloody old thing, built in about 1923, and it carried about 80 or 90 tonne; I think it had carried sugar up the coast or something, and it was only about 50 or 60 feet long.

“I’d spent a lot of time down in the engine room on the old ship I was on, talking to the firemen, and they used to show me how to slice a fire, how to build the fire up, and how much air they needed to put into it … so on my application form, I’d put that I was a fireman.

“The Olga Topic had nine fires – three boilers with three fires in each boiler – and nine firemen … but the Bopple was only a little old ship with three little fires and one boiler. A schoolkid could operate it, so it was no trouble.

“I stayed on the Bopple all around New Guinea … right round to Buna, and right along the coast.

“We travelled backwards and forwards, carting supplies and taking out any casualties.

“Eventually we were at Finschhafen … and this beautiful-looking ship came in, the Armand Considere, and I’d never seen anything like it.

“It was brand spanking new and it was painted green. I’d only ever seen steel ships, and half of them were rusted, or had rust coming through, but this one was all shiny green.

“It was nearly 300 feet long and carried about 8,000 tonnes, but it was made of concrete … just the same as your footpaths and your gutters.

“I’m standing out there admiring it – this beautiful, shiny new thing – and the captain of the Bopple sent word down that he wanted to see me.

“They wanted me to transfer on to the Armand Considere that afternoon, so after dinner, I picked all my gear up, and packed my bag, and walked up to this green ship and down to the bridge.

“I’d never seen a green ship before, and the captain there said to me, ‘You’re the new fireman … Harry or Bill, or whatever his name is … he’s going home to America tomorrow ... and he's the one you’ll be relieving … so he’ll show you around.’

“I went down to the engine room, and I was lost, totally lost. It was a beautiful modern ship, and it was an oil burner. There were no fires, no coal, and everything was nice and clean.

“I’m looking at this ship, and it’s nothing like the bloody old ship I’m on; there’s valves here and valves there, and pipes here and pipes there, and it’s all clean and spick and span.

“I said to the young fellow down there, ‘You’ve got troubles, mate, you’re not going back to America.’

“He said, ‘What do you mean? I’m going home tomorrow.’ And I said, ‘I don’t think so. I don’t know anything about this. I’ve never fired a ship like this in my life. I don’t know the first thing about it.’

“He said, ‘You will by tomorrow morning! I’ll stay with you … and by the time you’ve done two watches, you’ll know as much as I do.’

“And that was it. I was off the old Bopple. And if I’d won Tatts Lotto, I couldn’t have been more pleased.”

Finschhafen, New Guinea, 1944: An aerial view of the harbour showing the shipping and port installations.

One of about two dozen concrete ships built during the war, Armand Considere was launched in May 1944, and delivered to the US Army four months later to be used as a store ship in the Pacific. Len would spend the remainder of the war on board Armand Considere, serving in the Philippines, Japan and eventually China.

“The old Armand Considere was like Bunnings,” he said.

“We carried everything that was required for the army, navy and air force … and if they wanted spare parts for this, or additional parts for that, it was almost certainly on the ship.

“It was like a big warehouse. We had just about anything anyone wanted, and if they’d wanted a tank track, we could have given them a tank track.

“It was full of bins … bins of this, bins of that, big bins, little bins, bins of everything … and we could give them anything.

A wharf used by the US Army Small Ships Section in the south-west Pacific area.

“Without a doubt, we would have been the number one prize as far as the Japanese were concerned, and that’s why the ship was painted green.

“When we weren’t under steam, we were told to get in as close as we could to the islands and hide.

“In some places we were that close to the jungle, or the coconut palms, that we could almost hit them with a stone.

“If we wanted to unload anything, we would take the ship in to the wharf if we could, and then bolt back in as close to the jungle as we could get and anchor under the trees.

“Every day, the Japanese would fly over us and attack other ships further out.

“We could see it all going on around us. And that was just the start of it.”

New Guinea, 1943: An American landing barge of the US Small Ships Section proceeding up the creek to their daytime hideout.

New Guinea 1943: Members of the US Army Small Ships Section tucked away in their daytime hideout.

In October 1944, Armand Considere formed up as part of a convoy heading towards Leyte. Today, the battle of Leyte Gulf is considered to have been the largest naval battle of the war, and one of the largest naval battles in history. A decisive air and sea battle, it effectively crippled the Japanese surface fleet, permitting the recapture of the Philippines, and reinforced the Allies’ control of the Pacific.

“Before we sailed, the captain said to me, ‘Do you think we can maintain such and such speed,’ and I said, ‘I couldn’t really say…’

“I’d only fired the ship from the dock, a couple of kilometres across the bay to hide, and then back again to unload something heavy on the pier.

“I’d never fired it over any distance, so I said, ‘I don’t know Captain, but I tell you what, I will get the last bloody ounce out of the boilers, and I’ll red-line it for you, and we’ll try our bloody best.’

“The next morning, we all started lining up, and we set sail, 104 ships … and about 50 naval ships.

“There were several rows, and they might have been 10 deep, 10 in a row, going right out … row after row. You couldn’t see it all, even if you got on the highest point of the deck.

“And in come the navy – the Americans – with the big battle wagons – destroyers, destroyer escorts, corvettes – big ones, little ones – and one or two Australians.

“You would see the destroyers, and the destroyer escorts going up and down and I felt real good, real confident, to see those bloody naval ships going up and down all around me at terrific speed.

“We zigzagged as we went north … and every three or four hours, the whole convoy would turn so many degrees, but every time we turned, we needed a few more revolutions … which meant we needed a bit more steam, and I couldn’t give them anymore. I had it red-lined, and we had to drop back.

“This ship comes up alongside us and some bloody rotten Australian starts yelling: ‘Get out of the bloody way.’ The ship I was on was all American, and he was a dinky-di Aussie. ‘Get out of the bloody way.’ And I felt good; I wasn’t the only bloody Australian after all.

“After the second morning, I got up on the deck to see what the weather looked like and to have a look around, but I couldn’t see anything.

“I went over to the port side, and I couldn’t see a ship anywhere, so I went right up on to the bridge to have a look, and there was not a bloody ship to be seen.

“They were all gone – the naval ships, everything – and we were on our own. And if you think that I felt lonely, you’ve got no idea.

“We were a number one priority for the Japanese if they had of realised it, and we were plodding along on our own, heading up into Leyte … and oh, goodness, gracious, it was terrible.

“This terrible naval battle was going on 10 or 15 mile up the road, and we could hear a lot of explosions as we were coming in, and we could see the sky.

“The air force battle was still going on around us and a lot of ships were destroyed.

The Japanese signed the instrument of surrender on board the American battleship, USS Missouri.

The surrender of Japan aboard USS Missouri: After the signing ceremony and the Japanese representatives had left the Missouri, aeroplanes flew over the Allied ships anchored in the bay.

“The Americans lost something like four aircraft carriers, and the Japanese lost four or five as well … And that was just the aircraft carriers.

“The Japanese lost over 400 fighters up there in 24 hours, and that was the end of the Japanese air force; they were just about all destroyed.

“We high-tailed it as close to the jungle as we could get, and that’s when I saw the first kamikaze.”

Len went on to serve in Manila and was at Okinawa when the Americans dropped the atomic bombs in August 1945.

“The planes went over us to Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” Len said. “The captain said to me the next morning, ‘You’ll be going home soon, Len; they’ve dropped the A-bomb on Japan.’

“I thought he meant a bomb, not the A-bomb. It was the first time we’d ever heard the terminology – A-bomb – and I said to him, ‘A bomb? From what I’ve seen, they’ve they dropped more than a bloody bomb on Japan.”

Japanese representatives await the opening of the signing ceremony aboard USS Missouri.

Japanese Foreign Minister signing the instrument of surrender on behalf of Japan.

Len was in Tokyo Bay on board Armand Considere when the war ended on 2 September 1945. He had taken an unsanctioned trip into Yokohama four days earlier and caught the train into Tokyo. No one would talk to him, or look at him, and the captain told him not to mention it again in case he was court-martialled. He still remembers watching from the deck of Armand Considere as officials boarded the American battleship, USS Missouri, to sign the surrender documents, officially ending the Second World War. He had just turned 19.

Len stayed on Armand Considere after the war and served in China as part of the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. The scale of devastation and the horrific loss of life he saw in Shanghai affected him more than anything else he had seen during the war.

He returned to Australia in 1946, and went to work on oil rigs in Bass Strait. He didn’t speak about the war for decades, but helped his brother make the brass dish for the Eternal Flame at the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne. Designed by Ernest Milston, the Eternal Flame was lit by the Queen in 1954, and has burned ever since.

Len returned to the Philippines and China in 2019. Photo: Courtesy Len McLeod

Len's own service was not officially recognised with the awarding of the 1939–45 Star until 75 years after the war. When the war ended, Len’s AIF service in New Guinea was just days short of qualifying for the medal, and the eligibility of Small Ships veterans was not recognised by the Federal Government until 2010. Proving his participation in the Small Ships was also difficult, as records for the Small Ships were often scarce or missing.

Part of the ‘forgotten fleet’, Len returned to Manila and Shanghai in 2019, and was finally presented with the 1939–45 Star in a small ceremony with family and friends at Kingaroy Town Hall in July 2020.

“I couldn’t believe it when it came through,” he said at the time.

“Growing up, my mother had told me all about the First World War, and how that was going to be the war to end all wars, but suddenly that was all shattered, and all my mates were going away.

“They were all the same as me, and they all did what they were expected to do for the country.

“I got thrown out a few times, but I kept going back with different names and one thing and another, until finally I got away.

“I’ve got just about the whole collection of medals now … and I’m not bad for an old fellow.

“But I’m very lucky to be here.”

Len McLeod visiting the Australian War Memorial in Canberra in 2021.