“We could not get off the island.”

In June 1941, 12,000 Allied soldiers were left stranded on Crete. Many were left with only two options: surrender or hide. John Desmond Peck of the 2/7th Battalion did not surrender. Reflecting on this decision, Peck later mused, “We knew that the misery of the return journey under German forces had to be avoided at almost any price.” His survival, and that of his mates, was only possible due to the resistance of the people of Crete.

John Desmond Peck of the 2/7th Battalion was 18 years old when he was stranded on Crete. AWM2021.22.100

Peck moved along the coast searching for a way off the island with a small group of Australian soldiers. They came upon a small dinghy hidden in a sea cave and flipped a coin to determine who would get a seat. Peck was not among the four who left the island in the small vessel.

The remaining six men made their way inland to Klima. Despite German threats to burn villages and execute those found assisting Allied soldiers, the Venezelos family offered the Australians hospitality. Peck and his comrades recuperated for a few days before departing for the nearby rocky hills.

On 8 August 1941 a German patrol was seen near the hideout. After the group separated to avoid detection, Peck found himself in a precarious position. He had been keeping a safe distance behind the patrol in the valley below when he suddenly realised a second patrol was making their way down the hill behind him.

I did not know which way to turn. If I stayed where I was the hilltop patrol could not fail to see me hiding in the rocks as they came down. If I moved now the valley patrol would grab me.

Seeing an opportunity, he ran towards a small abandoned village. After several unsuccessful attempts to open locked doors, Peck came to a small square in the middle of the village, out of sight of the German patrols. Peck’s relief was short lived as he turned the corner and walked straight into a group of Germans drinking and washing in the village spring. Peck took the guise of a Cretan shepherd.

I bent double, putting my forefingers to my forehead like horns and went ‘Baaa, baaa’, at the same time peering forlornly all about in what I hoped was a perfect pantomime of Little Bo Peep.

Searching his pockets, a German sergeant found his Australian Army paybook.

His finger shot out and point straight between my eyes he said ‘Englander.’

‘Nein’ I [said] simply

That shook him. He looked at the paybook again, then back to me. ‘Englander!!’ he said again, this time with more emphasis.

‘Nein’

‘Ya’

‘Nein’

‘Ya’

‘Nein’

‘Ya’

By the screaming look on his face I knew this duet was getting a little strained so I ended on a high note. ‘Nein’ I said. ‘Australian’.

At Galatos prison camp, Peck spent his first four days in the “cooler”, a six-square-foot open-air barbed wire stockade. After this experience he began to plan his escape, but soon discovered that “the general opinion [of other prisoners] was that anyone who risked his life just to hide in the mountains until the war was over was little better than an idiot.” On 20 August 1941, Peck escaped alone.

Dodging German patrols, Peck returned to Klima. The Venezolos family greeted him with hugs and tears, and he had a “more subdued but equally moving” reunion with his comrades in the hills. The Germans in the area had increased their use of force and the men were eager to re-join Allied forces. However each escape plan reached the same disheartening conclusion: “We could not get off the island.”

Papa Venezelos soon delivered news that a British officer had landed a submarine to evacuate Allied soldiers. This news incited Peck to spend weeks chasing rumours of Commander Poole and his miraculous submarines. His faith was wavering when he encountered a large, red faced man. With a jolting realisation Peck exclaimed, “You’re Commander Pool!”

The man’s grin confirmed it. The submarine was real, but Peck had missed it by two days.

Poole asked Peck to return and pass word to those he trusted that another submarine would arrive in two weeks. This achieved, Poole suggested another assignment. “I was so bucked up that when he asked me to do another job I watched the rest of the boys head for the coast without a pang of regret.” This was not the last vessel Peck would miss.

When Peck contracted malaria, a local healer performed bleeding treatments. However, Peck continued to weaken, and a doctor arrived but only had a small amount of quinine.

Peck urgently needed to leave Crete. Setting off for Amari, he was assigned the young George Psychoundakis as his guide. Without medicine, Peck got weaker. Every time he fell, Psychoundakis hoisted him to his feet. In the end, the delay caused by Peck’s illness meant he missed the escape vessel.

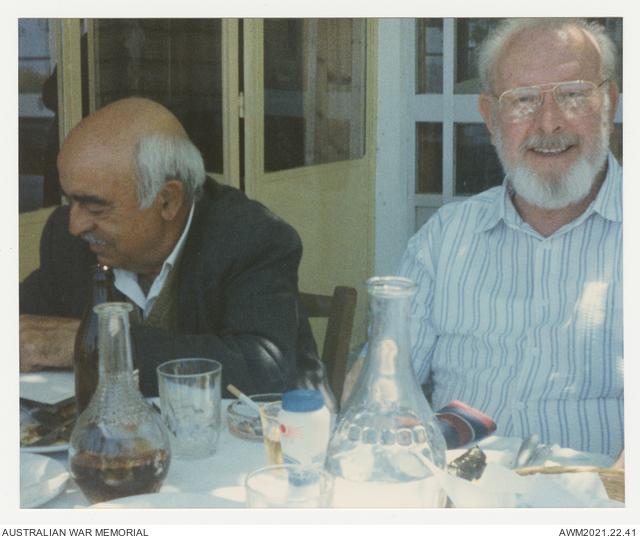

George Psychondakis, author of The Cretan Runner, pictured second from the left. AWM2021.22.41

In May 1942, Peck’s luck ran out and he was captured by Italian troops. Peck was taken to Rhodes Island where he received the death sentence for espionage before German forces confirmed that he was a prisoner of war. Although in enemy hands, Peck had made it off Crete.

Cretan partisans at Vafes, Crete, 1943. AWM2021.22.41

Peck never forgot the people of Crete:

We were very sorry to leave such good and kind people and knew that it was beyond our power ever to adequately repay them for what they had done for us at the considerable risk of their own lives.

Peck returned to Crete in 1990, and unexpectedly met George Psychondakis. The two relished catching up, each relieved to know that the other had survived the war. Photos and articles relating to their reunion are available in the collection.

George Psychoundakis [left] and John Desmond Peck in Crete, 1990. AWM2021.22.41

This is the second article in a sequence detailing the heroism of Lieutenant John Desmond Peck. For other articles in the series, please visit this page.

The Memorial has digitised the papers of John Desmond Peck [PR03098] and made them available online as part of the Memorial’s Digitisation Project. The collection is available here.