Dancing cheese and Kookaburras: rare costume designs offer a unique insight into the First World War

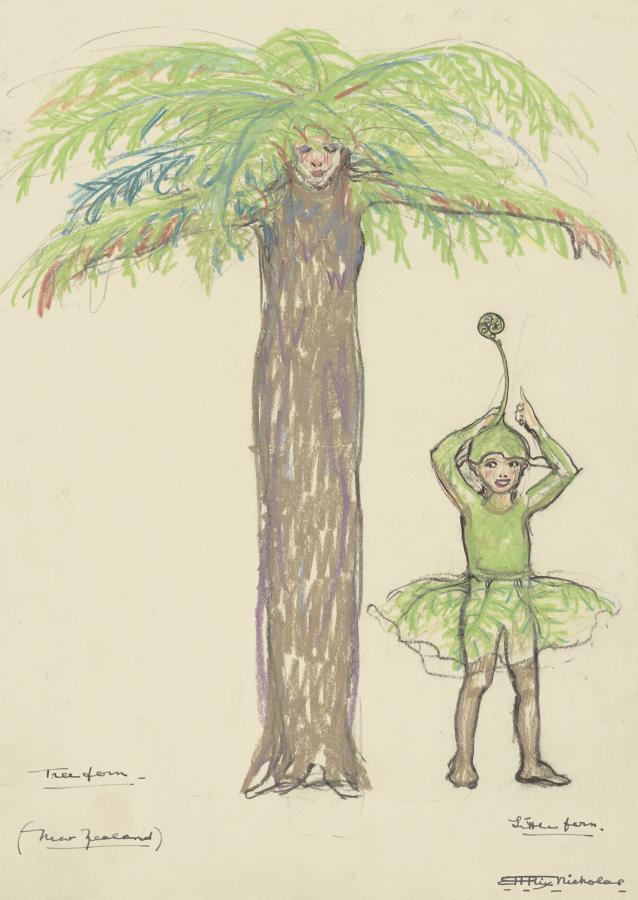

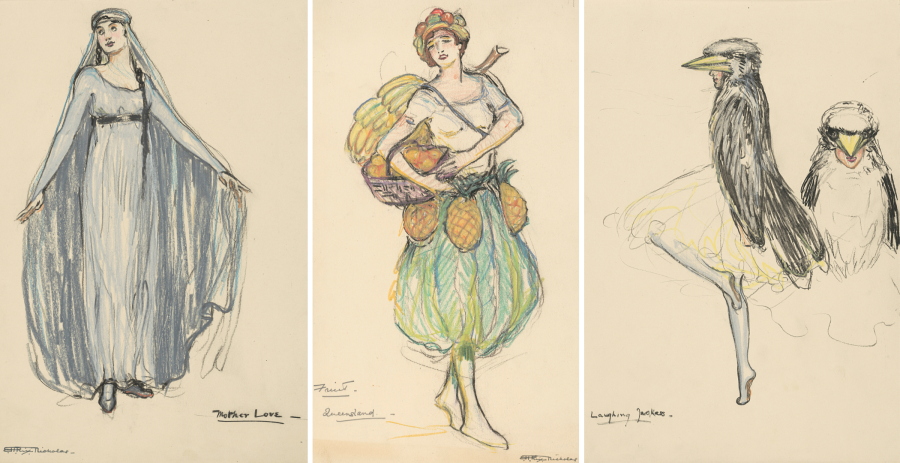

Hilda Rix Nicholas, Costume designs for Pageant of the Southern Cross, 1917, (L-R) Mother Love, AWM2024.582.14; Fruit, Queensland, AWM2024.582.1; Laughing Jackass, AWM2024.582.25. Courtesy of the Artist's Estate.

Costume designs by artist Hilda Rix Nicholas are the only surviving images of 1917 Anzac Club and Buffet fundraising pageant.

The Pageant of the Southern Cross was an allegorical pageant play, performed at Victoria Palace in London on 19 October 1917 to raise funds for the Anzac Buffet. With few surviving records of the pageant, the only known colour images are costume designs by Australian artist Hilda Rix Nicholas (1884–1961). The Memorial has acquired 39 designs in coloured crayon from the artist’s family with the generous support of the Australian government through the National Heritage Account. These vibrant, evocative drawings allow contemporary audiences to gain impressions of the pageant, highlighting its conception and richness of colour, as well as revealing a little known aspect of women’s wartime work.

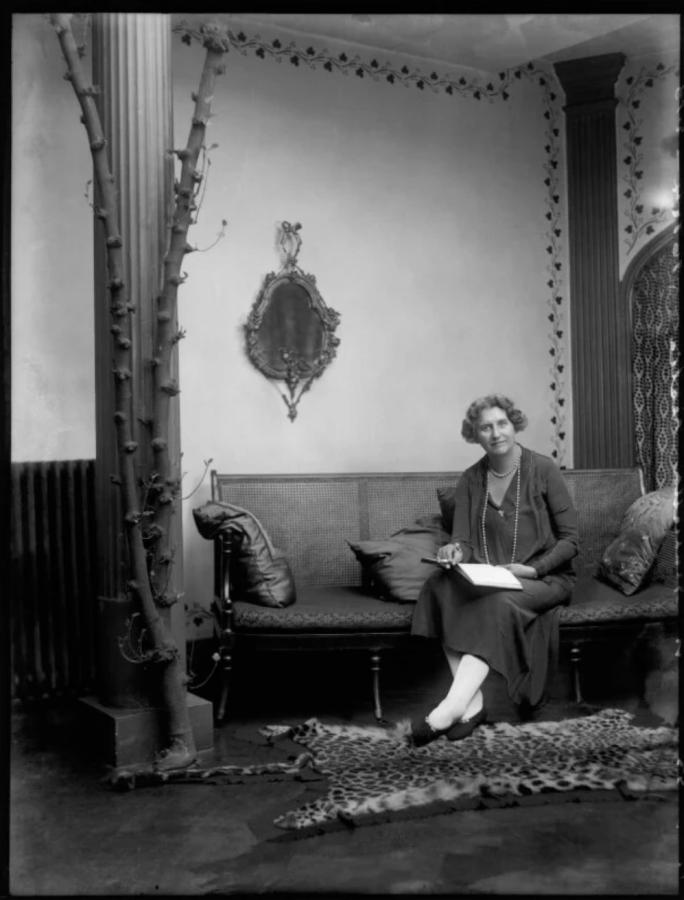

Photograph of artist Hilda Rix Nicholas, c. 1920, dressed as "the spirit of the bush". Courtesy of the Artist's Estate.

The Anzac Buffet

The Anzac Buffet opened in London on 13 September 1915 to provide meals, a reading room and other supports to Australian and New Zealander soldiers in London – at the time, the bulk were recuperating after being wounded on Gallipoli. Primarily run by the voluntary labour of Australian women, it became a home away from home for Anzac soldiers, providing a place to access free meals, socialise, and catch up on Australian news. As Australia’s role on the Western Front expanded, the buffet grew, moving to larger premises several times. According to press reports, by the time it closed in November 1919 it had provided 1.5 million meals for soldiers.

Fundraising efforts were paramount, and surely one of the most memorable was the Grand Matinee at the Victoria Palace on 19 October 1917, featuring the Pageant of the Southern Cross.

The Pageant

At the start of the First World War British author, journalist, pacifist and suffragist Gladys Henrietta Raphael Schultze (1882–1946) wrote Advance Australia in London to support fundraising for the Australian Soldiers Fund. Presented under Schultze’s pen name, Henrietta Leslie, the patriotic pageant play allegorically depicted Australia’s response to the call of Empire. What little is known about the pageant play (no copy of the original text is known to exist) comes from surviving programs and the reportage of the day.

Henrietta Leslie (Gladys Henrietta Raphael Schutze) by Basano Ltd, 15 May 1933, collection National Portrait Gallery

The plot involved performers personifying England, Australia and her six states, and concepts such as progress, space and freedom, mother love, old age and youth. As the curtains went up the audience could see England (Britannia) dressed in armour, standing on the prow of a dreadnought, or on a large rocky outcrop. Calling out for help, she is answered by the sound of gentle coo-ees from off stage. Australia enters the stage, accompanied by a page carrying her shield, and responds by offering England everything she has. One by one the states enter the stage, performing solo songs and speeches accompanied by retinues of dancers and children. Each group are presented as gifts, dressed in costumes symbolic of natural resources, which slowly gather at England’s feet. The performer portraying Queensland was accompanied by gifts of fruit, sugar cane and opals. Despite these gifts, England demands more, and asks Australia for her sons. Australia then consults Mother Love who summons Youth onto the stage before confirming:

“Oh, Mother, take/this gift, the greatest gift of all, but clasp/It lovingly, for thine keeping, in/The cup thou hold’st is poured blood/the very life blood of my heart.”

The pageant reaches its climax as Australian soldiers enter the stage as all join in singing Land of Hope and Glory.

The pageant was performed three times during the First World War: as Advance Australia in Melbourne (1916) and Brisbane (1918), and as Pageant of the Southern Cross in London in 1917. The three productions raised more than £3,000 (approximately $300,000 in today’s money) for charity, including £450 for the Anzac Buffett.

Front cover of the program for the matinee which included the pageant, 1917

The 1917 production was the most glitzy. Featuring almost 100 performers in spectacular costumes, the London production was expanded to represent the Anzac nations – Australia and New Zealand. This was reflected in the use of a new title, Pageant of the Southern Cross, and the inclusion of performers representing New Zealand, her islands and resources. The New Zealand contingent included Princess Iwa (1890–1947), the first Maori singer to establish an international career, who performed a Poi dance. A group of convalescent Maori soldiers impressed the audience with a Haka.

The pageant was produced by Australian born actress and suffragette Inez Bensusan (1871-1967), who enticed “Practically the whole of what one might call the Anglo-Australian stage” to perform.

This included British starlet Lily Brayton (1876–1953), Australian opera singer Ada Crossley (1871–1929); Australian actresses Alice Crawford (1880–1967) and Madge Titheradge (1887–1961); New Zealand born actresses and singers Eve Balfour (1882–1955), May Beatty (1880–1945), Princess Iwa and Rosina Buckman (1881–1948), and Scottish-born Australian matinee idol Julius Knight (1862–1941). These popular performers ensured the production was well supported and reviewed, and reported on in Australia. The chance to join the celebrities on stage would have thrilled the amateur performers undertaking supporting roles.

The Costumes

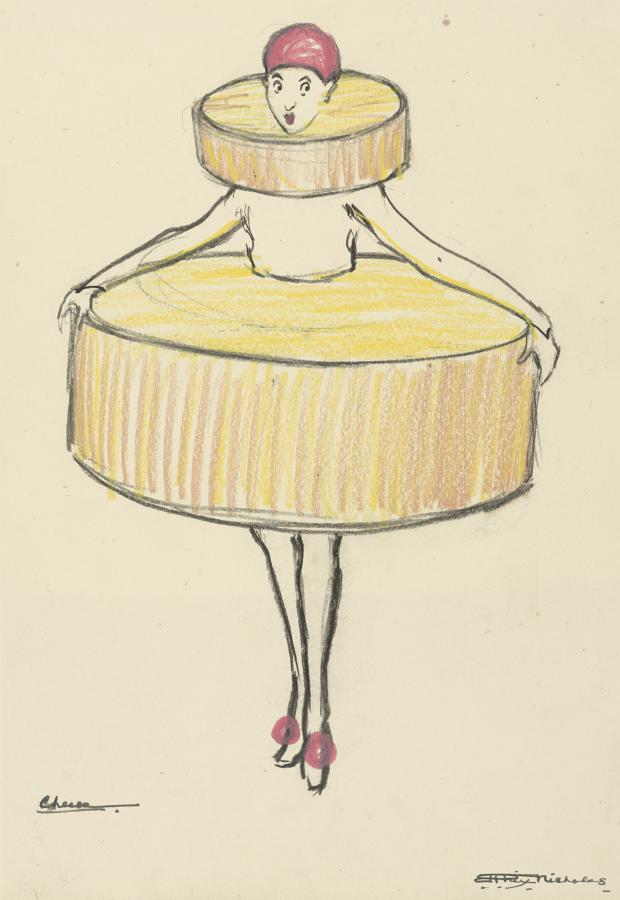

Hilda Rix Nicholas’s 1917 costume designs demonstrate her inventive and ambitious approach to dressing performers.

Hilda won acclaim in France and England for her drawings in coloured pastels. In addition to having undertaken classical art training, which included mastering life drawing, Hilda studied with commercial artists John Hassall and Theophile-Alexandre Steinlein. Her designs for the Pageant of the Southern Cross are lively figure studies. The poses and expressions are theatrical with many of the figures dancing. The artist seems to have taken delight in their creation, embellishing several of the figures with sweet drawings of related decorative elements or props. A ram appears behind the figure representing wool, and a cockatoo is perched on the shoulder of a jackaroo character representing timber. Other figures are drawn with props such as bowls of fruit, hats, and staffs of various kinds. These are joyful works showing the artist’s eye for design, and love of colour.

The collection allow us to see Hilda’s working process. Several drawings are quick preliminary studies in pencil, others with colour roughed in. From these first ideas it is likely that she worked up the more complete coloured drawings for the pageant’s production team.

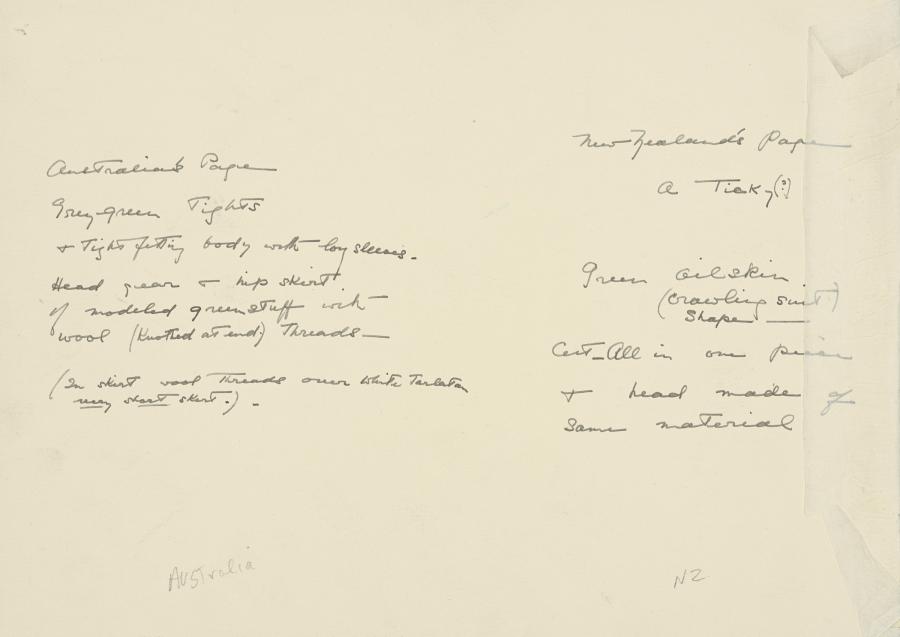

Hilda describes how the costumes will look for Australia and New Zealand, AWM2024.582.16. Courtesy of the Artist's Estate.

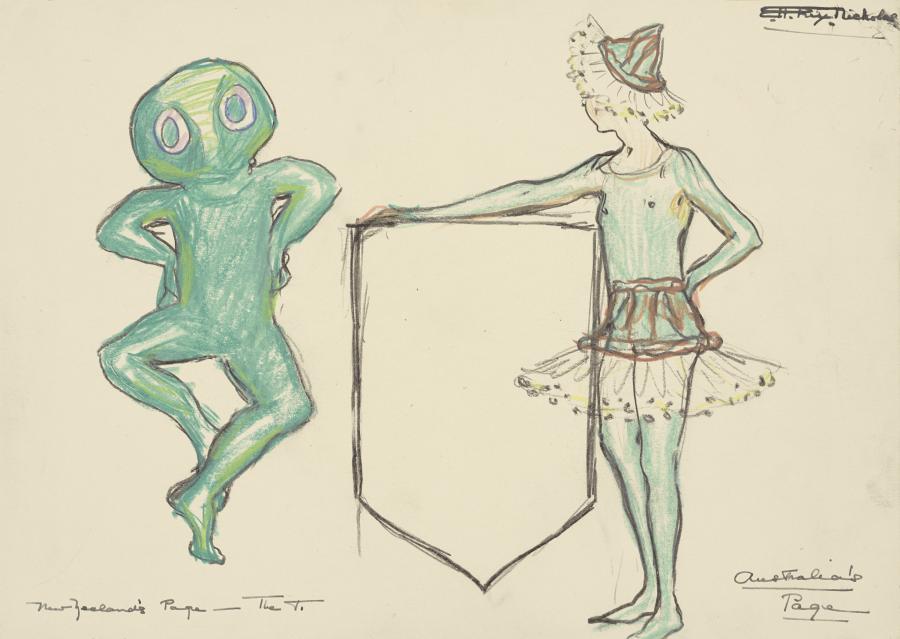

Hilda provided written notes on the back of the designs proposing fabrics to be used in their creation – ranging from satin to tarlatan and oil skin – and notes on the construction of more ambitious designs. She describes how the costume for Australia’s page is to include grey, green tights and a tightfitting body with long sleeves, a green hat and hip skirt modelled in green stuff with wool threads knotted at the end. She suggests that the blossomed skirt is to be made from wool threads over white tarlatan. For New Zealand’s page, a greenstone Tiki, a suit cut from one piece is to be fashioned using green oilskin with a head made of the same material.

Illustrations for the New Zealand and Australia costumes, AWM2024.582.16. Courtesy of the Artist's Estate.

A tree fern could be constructed with the clever use of casement linen to create the textured trunk. A whimsical design for cheese includes instructions that the performer be dressed in a “White tight jacket long sleeved - cherry coloured skull cap - very whitened face red lips” with cheese constructed using cardboard boxes papered yellow. A highlight of the collection are drawings for birds (magpie and kookaburra) with a suggestion to create their “feathery parts” using calico. These were perhaps too ambitious, as birds are not among the costumes noted by reviewers. Waratahs, sarsaparillas, flannel flowers, gum blossoms and wattle, however, are noted as being among the many costumed performers.

While Hilda’s notes reveal her skill as a costume maker and seamstress, she did not lead the physical production of costumes. This was undertaken by British sculptor, painter, illustrator and author Miss Melicent Stone (1868–1922). Unfortunately there are no known flash photographs of the 1917 performance or costumed performers to see how the designs translated to reality.

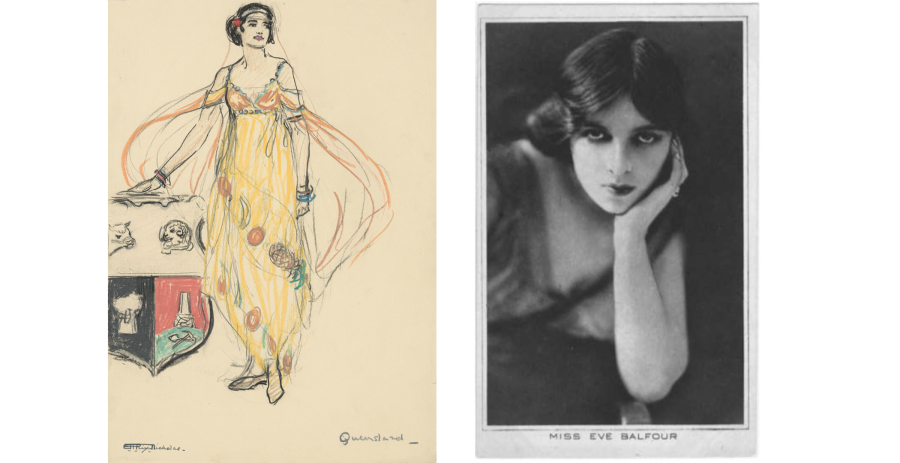

Surviving designs include those for the roles of Australia and New Zealand (Zealandia) and the six Australian states. Each of the states are drawn in flowing classical robes, adorned with produce or other items symbolic of their state, and are posed with heraldic shields. A design for England or Britannia is not among the collection. It is likely that Hilda did not feel the need to draw Britannia, an instantly recognisable figure for most citizens of the Empire. Britannia was often portrayed during the war in a large array of wartime propaganda and paraphernalia, including brooches, fundraising badges, greetings cards, posters, cartoons, advertisements and popular songs. Conventionally shown as a golden haired female warrior dressed in white classical robes, helmeted and holding a trident and a shield, she came into many Australian homes on next of kin commemorative medallions.

With leading roles performed by some of the most well-known stars of the era, Hilda may have been aware of for whom she was creating costumes. Hilda’s design for Queensland (AWM2024.582.12) bore a passing likeness to the glamourous New Zealand-born silent movie star Eve Balfour who appeared in the pageant adorned “in flowing satin the colour of persimmons”.

Hilda Rix Nicholas, Costume designs for Pageant of the Southern Cross, 1917, Queensland AWM2024.582.12, Courtesy of the Artist's Estate; Eve Balfour, published in the Daily Mirror, 26 October 1916

Nearly all of the designs are signed “EHRixNicholas”, and as such are among the first of works inscribed by the artist with her married name. Major George Matson Nicholas, Hilda’s husband of 41 days, had been killed on the Western Front in November 1916. Having already lost her mother and sister, Matson’s death pushed Hilda into deep despair. Among friends in London who supported her during this time were almost certainly the painter Mary Raphael and her daughter Henrietta Leslie, the author of the pageant.

It may seem incongruous that Hilda could create such joyful drawings during a dark period of her life. However, like many expatriate middle class women living in London, she would have felt a responsibility to volunteer her talents and labour in support of the war effort. Fancy dress and theatrical events had been a beloved part of her social life from childhood, so the task likely provided a sense of purpose and a welcome distraction.

The designs are a rare record of an event that expressed how countries understood and represented themselves internationally, celebrating the environments that made them distinct, and the natural and industrial resources that defined their economies. While fundraising events were common during the war, it is highly unusual for records such as these to have survived, especially with the involvement of an artist of this calibre.

The acquisition of Hilda’s costume designs for the Pageant of the Southern Cross means that the Memorial now has the largest collection of Rix Nicholas’s wartime work in the world.