The worst night in Australian military history: Fromelles

From March 1916 Australian divisions began arriving in France. Initially the troops found a pleasant land and a welcome change from sea voyages, the cliffs of Gallipoli, and the training camps of Egypt. There were four divisions, each about 20,000 men, and they were sent to French Flanders close to the Belgian border. Now, for the first time, the AIF was at the main theatre of the war.

Informal outdoors group portrait of soldiers and officers from a battalion of the 6th Brigade who were newly arrived in Flanders from Egypt

The Australians were given a gradual introduction to the Western Front fighting conditions. It was a new experience for them. They trained with some of the latest weapons of modern warfare including poisonous gas. Things became more serious when they moved into the front line trenches in a section around Armentières which had been dubbed "the nursery".

Meanwhile the British army, under Sir Douglas Haig, was about to conduct a mighty offensive in the Somme region, 100 km away to the south. The battle was set for 1 July, and it would continue for five months. It began disastrously; there were 58,000 casualties on the first day and little ground was taken. As the fighting went on three Australian divisions, the 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions, were eventually drawn in, leaving the 5th Division under Major General James McCay, behind. This newly arrived 5th Division would be the first to see heavy action.

Just beyond the line held by the Australians in the nursery sector was the shell-damaged village of Fromelles standing on a strategically important ridge behind the German front line. The surrounding battlefield had been fought over by the British during 1915, and now a fresh attack against the ridge was planned. It was hoped that a strong diversionary attack here would prevent the Germans sending troops to reinforce their defences on the Somme. The attack was set for the evening of 19 July and the Australians and another untried British division, the 61st, were chosen to make the effort.

The attacking troops were not familiar with Fromelles itself because it was in German hands; for them the nearest village was Fleurbaix which stood behind their own lines. For a long time afterwards many would refer to the events about to unfold as the battle of Fleurbaix, but eventually the name of Fromelles stuck and today it is by that name that the battle is known.On this battleground the opposing trench lines faced each other across a flat, boggy and overgrown no man's land criss-crossed with drainage ditches and a small stream. Because of the high water table, the trenches were mostly above-ground breastworks. Of deadly concern, sited within the enemy lines was the "Sugarloaf" salient. This was a heavily manned position with many machine-guns that jutted towards the British lines. Fire from here could enfilade any troops advancing towards the ridge. The enemy held the high ground and all of the advantages.08.

Battle of Fromelles by Charles Wheeler. Depicts a panoramic view of the Sugarloaf Salient area at Fromelles, with men of 5th Division AIF crossing No Man's Land towards the German trenches.

The attack began at 6 pm on 19 July. The Australians were on the left, the British division on the right. Unfortunately, the preparatory fire from the artillery had failed to do much damage. Worse still, the attempts to quickly capture the Sugarloaf and remove the threat from there failed. It left the Australians' brigade on the right, the 15th, to face murderous fire and to suffer alarming casualties. Further to the left of the attack there was some initial success as the 14th and 8th Brigades reached the enemy's positions. However, the Australians mistook a muddy ditch as the enemy's third line. Men worked to consolidate the ground taken, often trying to fill sandbags with gluey mud to form a parapet. Machine-gun and rifle-fire cut down many of those trying to bring up ammunition and supplies.The fight went on into the night but the darkness brought little reprieve. The heavy fire from machine-guns and artillery, and the German counter-attacks, took a heavy toll. The Australians were told to hold on to increasingly impossible positions and as midnight approached even more men were poured into the battle. Meanwhile the artillery could not provide enough protection as it had trouble locating the respective battle lines. Sometimes the shelling effectively broke up enemy counter-attacks, but sometimes the rounds fell on Australian positions.

Part of the German front line after the Battle of Fromlles which took place on 19 July 1916 and 20 July 1916.

Sections of lines were still stoutly held by the Germans. At other points the Australians were holding on to the ground gained, peering into the darkness not knowing where the enemy faced them. Suddenly the Germans might attack from the front, the sides or from the rear. In these murderous conditions, with no chance of holding on, the remnants of several battalions fought their way back to their own breastworks. This movement spread. The situation was deteriorating and it would get worse when daylight came. The Germans suffered losses too. The cries and moans of their wounded mixed with those of the Australian and British soldiers. There was also the mournful sound of horns; it was the enemy's call for stretcher-bearers.

France. 10 October 1916. An aerial view taken during the tour in the Line of the 5th Australian Division showing mine craters between the German and Australian lines, situated 2,000 yards north of Fromelles

Early in the morning while Major General McCay was still considering further attacks, he received reports of the overnight disaster and passed the news to the British commander and architect of the whole scheme, General Richard Haking. It was obvious that the idea of any further attacks had to be abandoned. By mid-morning most men who were able had withdrawn to their own starting lines. However, many of the wounded had to be left, while some groups of men became surrounded and had to surrender. At 9.20 a German officer noted that the remaining enemy had withdrawn, or been captured. Almost 500 Australian and British troops became prisoners of war.

Captured Australians arriving at the German collecting station on the morning of 20th July during the Battle of Fromelles which took place on 19 July 1916 and 20 July 1916.

The 5th Division had suffered terribly. Some brigades having lost their most talented officers and hundreds of men, seemed to have been almost destroyed. Brigadier General "Pompey" Elliott had tears in his eyes as he greeted the returning remnants of his 15th Brigade. Some battalion commanders were similarly observed. The recovery of wounded went on over the next three days and nights. The Germans gathered in many behind their own lines and elsewhere sometimes shifted men to where the Australians might reach them.Several decades later the gathering in of the wounded became the inspiration for a memorial erected at Fromelles. In July 1998 a major sculpture, Cobbers, by the Melbourne sculptor Peter Corlett was unveiled. It depicts a man carrying a wounded comrade on his back and is based on an account of the deeds of an Australian stretcher bearer, Sergeant Simon Fraser. The title of the memorial recalls the plea of one wounded soldier, "Don't forget me, cobber." Fraser was killed later in the war.

Portrait of 2nd Lieutenant Simon Fraser, MID, 58th Battalion, killed in action 1917-05-11.

Having driven the attacking forces back, the Germans re-occupied and re-developed their trenches which were surrounded by the dead from the fighting. Many of the British and Australians killed in the battle were later buried by the enemy. There were other parts of no man's land were the bodies lay exposed, unable to be reached, for the next two years. Immediately the war ended, Australians went back to Fromelles. "We found the old No-Man's Land simply full of our dead. In the narrow sector west of the Laies River and east of the sugar-loaf Salient, the skulls and bones and torn uniforms were lying about everywhere."

The Australian 5th Division had lost 5,533 men in one night's action, and the British losses (from a smaller force) totalled 1,547. Australian deaths numbered about 2,000, and of this figure 1,299 would eventually be declared to be "missing". Most of the prisoners taken by the Germans were Australians.

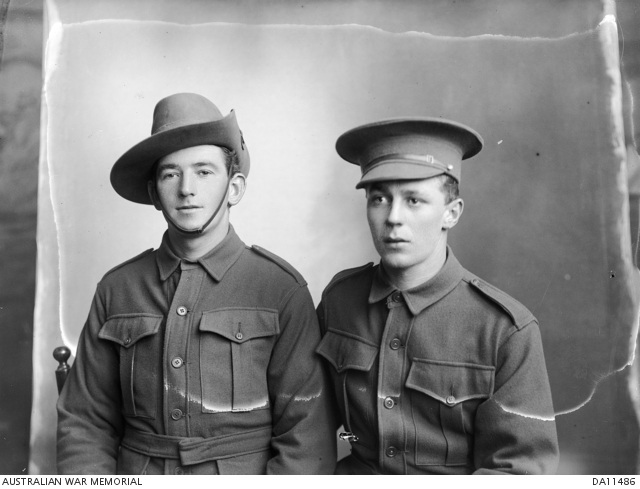

Studio portrait of two privates. Identified, left to right: 944 Private (Pte) Albert Stiles, of Williamstown, Vic, and 891 Pte Thomas Walker Jones, of Flemington, Vic.

The losses incurred at Fromelles made this battle the most expensive in terms of lives lost over a 24-hour period in Australia's war history. It must be remembered, however, that there were heavy losses throughout the war, and there were other days that were almost as terrible. In addition, there would be battles that would go on much longer with the death reaching even a higher level. For example, there were many more Australian deaths in the battle of Pozières, which began just a few days after the disaster at Fromelles and lasted almost seven weeks.

The high proportion of those men killed whose bodies were either not recovered or could not be later identified added to the tragedy at Fromelles. It also brought about a unique memorial on the Western Front, called VC Corner. The memorial stands over 410 Australian graves in a cemetery bearing no headstones; each man was lost in the battle. Their names, with almost a thousand others, are on the memorial's wall and each one of these 1,299 names represent an Australian lost or unidentified after the fighting.