Harold Edward “Pompey” Elliott

An inspiring and outspoken leader, Elliott was a Boer War veteran with extensive military experience. Even so, he was acutely pained by the enormous losses sustained by his men at Fromelles.

Harold Elliott was born in Victoria in 1878. He studied law at the University of Melbourne, serving in Ormond College’s officer corps. Elliott was a successful athlete, winning scholarships and sporting competitions alike. In 1900 he interrupted his studies to enlist in the 4th Victorian Imperial Contingent and fought in the Boer War, where he was Mentioned in Despatches and awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. He later completed his studies and established his own firm of solicitors in 1907, while still serving with the Militia.

Elliott married Catherine Campbell in 1909 and they had two children, Violet and Neil. In 1913 he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given command of the 58th Battalion under the new universal training scheme. This scheme, introduced by Prime Minister Alfred Deakin in 1909, was essentially compulsory military training for males aged 12 to 26, and was intended to provide the nation with a degree of home defence.

At the outbreak of the First World War Elliott was given command of the 7th Battalion in the newly raised Australian Imperial Force. Around this time the nickname “Pompey” was bestowed upon Elliott, apparently inspired by Carlton football player Fred “Pompey” Elliott.

Elliott landed on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, but was shot in the foot and evacuated to hospital. He eventually re-joined his battalion and commanded his battalion in the battle of Lone Pine. He was evacuated twice more during the campaign owing to illness and injury.

Elliots bullet-damaged leather shoe, which he donated to the Memorial in the 1920s.

Following the evacuation from Gallipoli in December 1915 the AIF underwent a period of reorganisation and expansion in Egypt. As part of this process, Elliott was appointed commander of the 1st Brigade before being promoted to brigadier in March 1916. He was tasked with organising and training the newly formed 15th Brigade as part of the 5th Division, which was soon sent to France to fight on the Western Front, just days before participating in the battle of Fromelles.

Elliott was of the opinion that the attack at Fromelles was doomed to fail. He felt that the artillery was inexperienced, that the space to be travelled across no man’s land was too wide, and that the German army’s elevated and well-defended area known as the Sugar Loaf gave the enemy a strong advantage. He argued unsuccessfully to cancel the attack, but at 6pm on 19 July 1916 his brigade launched its attack with the other units of the 5th Division.

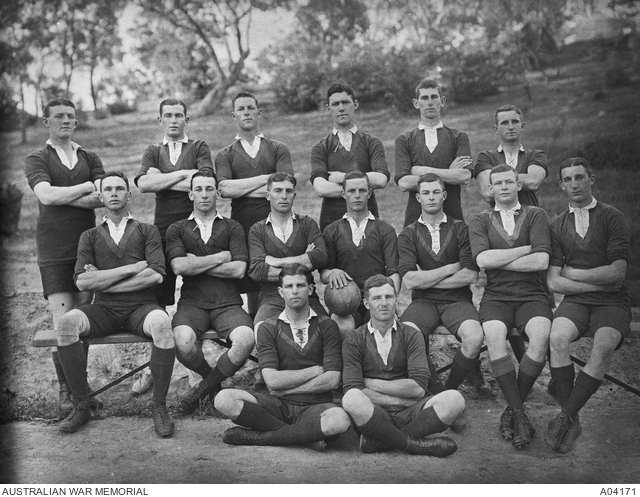

Members of the First XV rugby team at the Royal Military College, Duntroon, Canberra, 1913. Tom Elliott is in the back row, fourth from the left. Five of the men in this photograph were killed in action during the First World War.

One-third of Australian casualties at Fromelles came from Elliott’s brigade. Elliott met his men as they came out of the line, offering words of comfort to the wounded. Back at headquarters, Elliott reportedly “went straight back inside, put his head in his hands, and sobbed his heart out”.

Elliott was said to be particularly distraught over the loss of two of his officers. Major Tom Elliott (no relation), aged 22, had showed great potential as a leader, and Brigadier Elliott had tried unsuccessfully to keep him out of the fighting. Major Geoffrey McCrae, who commanded the 60th Battalion of the 15th Brigade, was a highly skilled and popular officer, and had served with Elliott on Gallipoli and in the Militia before the war. Elliott once wrote that if died in France he “should like to be buried near poor Geoff”. McCrae went in to the battle as part of the fourth wave over the parapet, and never returned. Elliott wrote often to McCrae’s father after the war, reporting on his son’s death and burial, on Fromelles, and on the issue of conscription, and also provided various updates from Europe.

Elliott continued to command the 15th Brigade on the Western Front, including during the battles of Polygon Wood, Amiens, Villers-Bretonneux, and Péronne. His brother George also served on the Western Front, but was killed after being struck by a shell fragment at Chateau Wood.

Elliott was known as an inspirational leader whose outspoken manner and criticisms of his colleagues and their decision-making, and of the way that some men were selected for awards over others, led at times to clashes with his superiors. Towards the end of the war Elliott expressed hopes to be given divisional command. This did not happen however, and his perception that others were promoted ahead of him became a great source of frustration.

Arriving home in early 1919, Elliott returned to practicing law. In 1920 he was elected to the Senate as a representative of Victoria, and was re-elected in 1925. He spent many years addressing parliament on his wartime grievances, including the issues around promotion.

In 1926 Elliott was given command of the 3rd Division, and the following year was promoted to major general, though his dissatisfaction with the military remained. In 1931 Brigadier Harold Edward “Pompey” Elliott took his own life. He was buried with full military honours in Burwood Cemetery in Melbourne.

Questions and activities

-

Why do you think the Australian government introduced compulsory military training for young men before the First World War?

-

Do you agree with compulsory military training? Why or why not?

-

How do you think Elliott felt about being evacuated from Gallipoli when his men were still fighting there?

-

What are the qualities of a good leader? Do you think Elliott was a good leader? Why or why not?

-

Read Elliott's service biography of Tom Elliott.

What does this document tell you about how Elliott felt about Tom Elliott and his death?

-

Have a look at these letters from Elliott to McCrae’s father.

Read the letter dated 26 January 1916.

-

What does Elliott write about McCrae in this letter? Why do you think he wanted McCrae’s father to know this information?

-

Elliott writes about missing out on promotions. What do you think was the reason for his disappointment?

-

-

Read the letter dated 21 July 1916.

-

Transcribe this letter. You may need assistance.

-

What does this letter tell you about Elliott’s thoughts on the battle of Fromelles?

-

Elliott compares Fromelles to the 8th Light Horse Regiment’s charge at Walker’s Ridge on Gallipoli. What is this charge more commonly known as? In what way did Elliott view these battles as similar? More information on the 8th Light Horse Regiment.

-

-

Frederick Wright of the 7th Battalion wrote of Elliott in 1915:

I would follow him anywhere, even to certain death.

When Australian War Memorial founder Charles Bean discovered that Elliott had died, he wrote:

So Pompey Elliott is gone! … The old soldier has laid down his arms … we can picture Pompey going round the turns of that long road that we all must travel some day, with his head held high, his senses alert, his strong chin set. It is not the first time that he has gone out alone into no man’s land. We know this about Pompey; he goes out as a soldier, utterly unafraid … History will do him an injustice if it does not hand him down to posterity as – with very few peers – one of the outstanding and most lovable characters of the AIF.

What do these quotes tell you about how Elliott’s peers viewed him? Why do you think these views differed from those of some of his superiors?

-

Read the following excerpts from a letter written by Elliott to his young son Neil:

Since I wrote to you before we got a lot of big waggons like traction engines and put guns in them and ran them “bumpety bump” up against the old Kaiser’s wall and knocked a great big hole in it and caught thousands and thousands of the Kaiser’s naughty soldier men and we killed a lot of them and more we put in jail so they couldn’t be naughty any more … it is very, very cold here and the Jack Frost here is not a nice Jack Frost who just pinches your fingers so you can run to a fire to warm them but a great big bitey Jack Frost and he pinches the toes and fingers of some of Dida’s poor soldiers so terribly that he pinches them right off. Isn’t that terrible … And the naughty old Kaiser burnt down every little house all round here and Dida’s soldiers have to sleep out in the mud or dig holes in the ground like rabbits to sleep in. And all the trees are blown to pieces by the big guns and there is no wood to make fires … Isn’t that old Kaiser a naughty old man to cause all this trouble. Now goodbye dear little laddie. Give dear old mum a kiss and tell her Dida’s coming home soon and that you will grow up soon and you won’t let any old Kaiser come near her.

Write a letter to a child from the perspective of a father at war. How would you explain events to a child that can be tragic, violent and incomprehensible?