The Simpson Prize 2021

The question

“How do lesser known stories from the Western Front expand our understanding of the Australian experience of the First World War?”

Instructions

The Simpson Prize requires you to respond to the question above using the Simpson Prize Australian War Memorial source selection (below) and your own research.

You are encouraged to debate, agree with, or challenge the statement from a variety of perspectives – individual, national, and global – and to use sources in a variety of forms.

You are expected to make effective use of a minimum of three sources listed below. Up to half of your response should also make use of information drawn from your own knowledge and research.

Information about word or time limits, the closing date, entry forms, and judging can be found at the Simpson Prize official website.

Note: Students who submit winning entries for this year’s Simpson Prize question will travel in 2021.

The competition is funded by the Australian Department of Education and run by the History Teachers’ Association of Australia.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people please be aware that this resource contains images and names of deceased persons.

The sources

Source 1a: Photograph

The Australian War Records Section (AWRS) trophy store at Peronne, France, where battle souvenirs were collected for the Australian War Museum, 1918. AWM E03684

Source 1b: Photograph

Lieutenant John Treloar (right) working at the Central Registry Office of the 1st Anzac Corps Headquarters, Henencourt, France, 1917. AWM E00380

Source 2: Photograph

Warrant Officer Harry Hoyling (of Chinese descent) wearing a sheepskin jacket and a gas respirator, France, 1916. AWM P01315.002

Source 3: Photograph

Australian soldiers after a snow fight at a training camp. The group includes Indigenous serviceman Private Alfred Coombs, England, 1916. AWM P03906.001

Source 4: Film

The Australian Army postal services at work, J.W. Smith and G.H. Wilkins, France and England, 1916–1918. AWM F00020

Source 5: Artwork

Harold Septimus Power, Evacuation of wounded horses in the battle line (1917, watercolour, charcoal, and pencil on paper, 37.7 x 53.5 cm) AWM ART03313

Source 6: Prisoners of war (book extract)

The unique position of Private Douglas Grant of the 13th Battalion demonstrates the ability of some men to stave off the chronic effects of barbed wire disease while trying to retain a sense of duty and military pride. Grant was one of twenty known Indigenous members of the AIF captured on the Western Front. Born around 1885 in the Australian Indigenous nations of the rainforests of northern Queensland, he has a unique pre-war story of being orphaned as a result of a frontier massacre. Adopted and raised by a Scottish taxidermist who worked for the Museum of Australia, Grant attended public school in Sydney and worked as a draughtsman and wool-classer before joining the AIF in 1916. Having first overcome racist regulations that prevented Indigenous Australians from leaving the country without government approval, Grant arrived on the Western Front in February 1917 and was captured at Bullecourt two months’ later. He spent several weeks recovering from grenade fragmentation wounds in a field hospital in France before passing through a number of camps in Germany. In a letter to Mary Chomley, Grant described himself as ‘a native of Australia, adopted in infancy and educated by my foster parents whose honoured name I bear, imbued me with the feelings and spirit of love of home, honour and patriotism’.

In January 1918, both Grant and another dark-skinned Indigenous Australian, Private Roland Carter of the 50th Battalion, were sent to the special Halbmondlager (‘crescent-moon camp’) for Muslim prisoners at Wiinsdorf-Zossen near Berlin.68 Carter was a labourer before the war and was the first Ngarrindjeri man to enlist in the AIF from the Port McLeay Mission Station on Lake Alexandrina in South Australia. Wounded in the shoulder and captured at Noreuil on 2 April 1917, Carter was treated at a German field hospital at Valenciennes, where he discussed Ngarrindjeri healing methods with German doctors.

Extract from:

Aaron Pegram, Surviving the Great War, Cambridge University Press, 2020, pp. 143–44

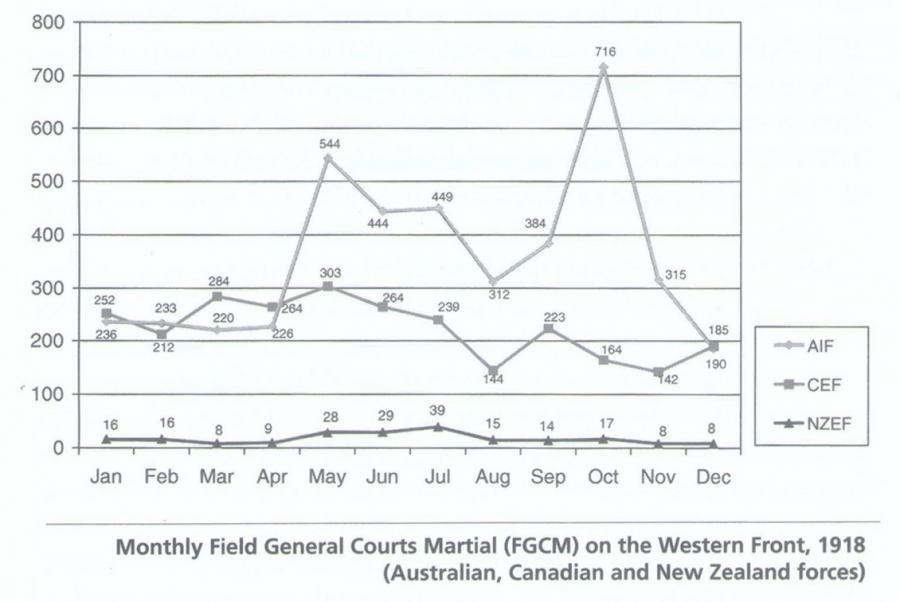

Source 7: Courts martial (book extract and graph)

The frequency of courts martial, primarily for the offence of desertion, increased during periods of intense operational activity, allowing for the delay between the dates of offences and sentencing. Within the Australian force, Field General Courts Martial on the Western Front reached a peak of 544 cases in May 1918, 80 per cent more than the Canadian total of 303 cases for that month. In October 1918 the Australian monthly total surged to 716 cases, the highest monthly total in the AIF for the entire war, and over four times the Canadian total of 164 for that month. This peak reflected the greatest period of operational stress for the understrength Australian units in late September.

Ashley Ekins, Fighting to Exhaustion, in Ashley Ekins (ed.) 1918: Year of victory, Exisle Publishing, Wollombi, 2010, p. 127

Source 8: Extracts from Diaries, Memoirs and Letters of Australian Flying Corps Officers 1917-18

There was a good deal of white archie [British Anti-Aircraft fire] about this morning and I was kept constantly at it. I saw one of our aeroplanes go down absolutely out of control and it subsequently turned out to be Streeter and Tarent. It is thought that their tailplane was shot away by one of our archie shells in its trajectory. It was Sheetin’s first turn on the line.

Lieutenant Owen Lewis, No. 3 Squadron AFC, diary, 17 February 1918 (AWM PR00709)

Had to make a good getaway from well over the Hun lines about a week ago. Six of us were attacked by 14 Fritzes. It makes one think of home sweet home as you see the bullets go past …

Two of us rather foolishly wandered too far into Hunland yesterday evening and were dived on by six Huns, and once again we had to make a hasty retreat, as the wind was blowing us away from our own lines as we stopped to fight, so we did not stop for too long as the air was unhealthy.

The squadron got its 100[th] Hun this morning, not bad going for 8 months work.

Lieutenant Thomas Edols, No. 4 Squadron AFC, letter to a friend, 14 July 1918 (AWM PR 86/385)

From the air the war zone of France looked like a scrawled and badly erased piece of paper. A few fragments of buildings, an odd ruin broke to monotony of the broken and shell pitted earth. In areas that had suffered heavy artillery barrages, it was literally impossible to walk between the shell holes … There had been life here before, but it had been systematically rubbed out.

Our own conditions were infinitely preferable … we enjoyed good food, plenty to drink and solid quarters … At one aerodrome we were billeted next to a champagne factory and could buy its wares, until we grew bored, for a bottle.

Captain Adrian Cole, No. 2 Squadron AFC, manuscript memoir, pp. 27-8 (AWM PR88/154)

5 September 1917: We do offensive patrols at about 15,000 to 18,000 feet well over the lines looking for a fight all the time. Our chaps brought down 3 of theirs yesterday and 2 today. And we lost 2 yesterday and 2 this morning (killed and wounded). So, things are pretty lively – four of our 18 pilots gone in two days.

9 September 1917: Went on my first ‘show’ in the PM with four other “Camels”. ‘It being my first real ‘go’ over the lines the others looked after me more or less and didn’t let any Huns get near me. The funny part about it was I didn’t see any hostile buses at all- at least I didn’t recognise them – although all the others fired at Huns at 4 or 5 different times.

10 September 1917: Had breakfast in bed and I got up at 10am to find the sky full of clouds and haze which stopped us going on our first jobs. However, it cleared up by 3pm. I took my place in a 5-plane formation. Soon after going over the lines we attacked 7 Huns (at about 13,000 feet) some of which dived away. MacMillan (the Flight Commander) dived after these and I followed him down to 8,000 feet where we each picked out a Hun and went for them. Mac shot his down out of control and I got a good burst on the other at close range and he suddenly caught alight, turned over and went down in flames.

2nd Lieutenant Raymond Brownell, No. 45 Squadron RFC, diary, September 1917 (AWM PR83/231)

Quotes from:

Michael Molkentin, Australia and the war in the air: Volume I - the centenary history of Australia and the Great War, Oxford University Press Australia, 2015