Out in the Cold: Australia's involvement in the Korean War - Medical Personnel

- Home

- Timeline

- Origins

- Australians in Korea

- Australian Operations

- Weapons of War

- Faces of War

- Armistice and Aftermath

- Glossary

- Australians in Service

- War on land: The Australian Army in Korea

- War at sea: The Royal Australian Navy in Korea

- War in the air: The Royal Australian Air Force in Korea

- Medical Personnel

In any war, the survival and health of serving personnel is largely due to the efforts and organisation of their medical personnel. The Australian doctors, dentists, nurses, stretcher-bearers and orderlies who served in Korea were no exception: they faced a wide variety of medical problems and challenges over the course of the war. Some Australian doctors who served in Korea were young, and had received little or no specific medical training for the trauma and injuries they would face there. Australian medial personnel worked with medical personnel of many other countries. The 60th Indian Field Ambulance in particular came to be highly respected by Australian personnel and patients alike.

Although there were many battle casualties and wounds among Australian servicemen, the mortality rate in Korea among Australians was 2.5% - a rate much lower than those of the two world wars. Most wounds were inflicted by small arms fire, such as machine guns and rifles, rather than by mortars or mines.

Apart from battle-related wounds, weather was a major factor in poor health, particularly among the ground troops who were forced to live in the cold of winter and in the extreme heat of summer. During the first year of the war, casualties were caused roughly in equal numbers by enemy action and the cold.

“Cold! I thought I knew it but Korea taught me otherwise. Cold so intense that even the ground was frozen solid and rivers iced up whilst a bone-chilling variable wind swept over the barren landscape. A weak sun rarely appeared in the leaden sky, vegetation withered and all animal life, with the exception of rats that infested our hoochies in plague proportions, vanished.”

Private Desmond Guilfoyle, 1 RAR

The incidence of frostbite was so severe in the first winter of 1950-51 that many of those afflicted had to be evacuated to Japan for treatment, which sometimes included amputation. It was particularly difficult to prevent because soldiers were on the move all the time and unable to take proper care of their feet, to change their socks daily, and give their feet rest.

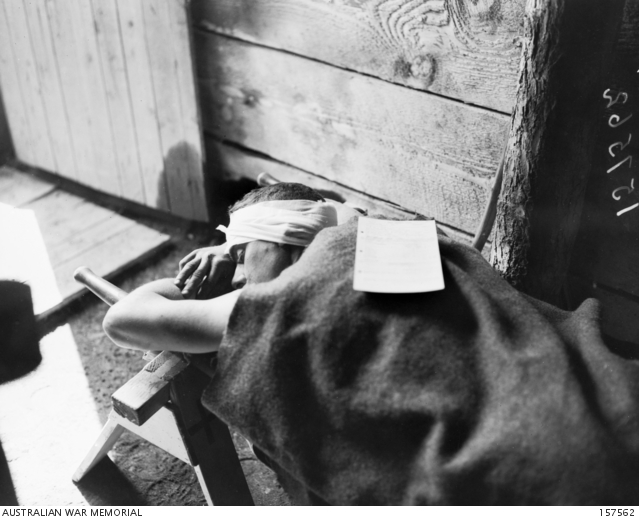

Private F.C. Smart, 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR), awaits helicopter evacuation from a 3 RAR Regimental Aid Post, after being wounded on Hill 355.

A doctor administers an injection of morphine to a badly injured soldier at Pakchon, November 1950.

Hill 614 area, February 1951.

A group of soldiers from C Company, 3 RAR, haul a wounded comrade, injured in both legs, on a stretcher.

Medicines, including penicillin, froze, and medical personnel expecting casualties warmed phials of medication in their pockets. In summer, heat and poor sanitation caused their own medical problems to a lesser degree, such as a variety of skin disorders.

Other medical problems faced included intestinal ailments, bronchitis, haemorrhagic fever, typhus, rheumatism, and venereal disease. The maintenance of good hygiene was crucial. Captain Bryan Gandevia, a doctor with the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR), wrote in notes to his medical staff:

“You are useless to us in the war against disease if you allow the Army's fifth column to destroy your personal hygiene, however fearlessly you may attack his well-defended positions such as lavatories, food and water supplies.”

Living in trenches was also responsible for medical complications, just as it had been for soldiers on the Western Front in the First World War. A condition called "Trench foot" in the First World War and "Rice-Paddy Feet" in Korea was the same problem - as a result of beingbeing immersed in water or snow for long periods of time, feet would swell painfully and peel. The condition often required a medical evacuation.

As in most wars, new techniques in medicine were pioneered. Australian medical teams in Korea developed new treatments in the repair of damaged blood vessels, saving many damaged limbs from amputation.

One of Australia's best-known and respected veterans, Major-General W. B. "Digger" James, then a Major, served and was wounded in Korea. After the war, he became a doctor and served in Vietnam.

Private Don Lamey, 3 RAR, was wounded in action on 16 July 1952. He carried these items as good-luck charms in Korea. The wallet, collar badges, dog tags and leather case had belonged to his father in the First World War. After initial treatment by an Indian Field Ambulance unit, Lamey was transferred in turn to a MASH (Mobile Army Surgical Hospital) unit, to a US Evacuation Hospital, and finally to the British Commonwealth General Hospital in Japan, before returning to Australia. REL 27796.001 -.004, .008

3 RAR stretcher-bearers carry a wounded soldier through the snow to the nearest aid post,

February 1951.

Warrant Officer 1 G.R. Gardiner instructs Australian nurses in rifle training before their departure for Korea. Authorities were concerned that North Korean troops would not respect the articles of the Geneva Convention protecting medical personnel and the sign of the Red Cross.

Because of medical evacuations by helicopter, the time taken to transport wounded to an established and well-supplied medical facility was normally quite short. However, this method had its limitations. Only two stretcher cases and two walking wounded soldiers could be evacuated at a time, and they could not receive treatment while in transit. In snowy conditions, when helicopters could not be used, medical evacuations had to be undertaken on the ground, often taking many hours to transport wounded to Regimental Aid Posts (RAP).

In the face of the rough terrain and the poor condition of local roads, helicopter evacuation was frequently the only option.

When Private M.C. "Snow" Dicker was wounded on 5 November 1950 from Chinese mortar shrapnel, he remembered waking up in a large marquee tent - MASH No. 8055:

“I was on a stretcher on the ground, and after feeling around a bit, I felt a large piece of sticky tape on my chest. I did not remember being hit there, so when the orderly came past, I asked him what it was all about. He told me it was the custom of the MASH units to keep the bullets, shrapnel, or whatever as a souvenir, and they stick it to your chest as a souvenir.”

Aerial evacuation also decreased the need for medical teams to be near the frontlines, or to be at risk of being captured as prisoners, a risk for many medical personnel during the Second World War. Nonetheless, at the frontlines there were still stretcher-bearers and medical personnel working in the battalions or as part of a field ambulance, who recovered the wounded and applied first aid.

At Maryang San, Sergeant Mark Young recalled that stretcher-bearers:

“… showed unbelievable courage in pulling out the wounded. If you've never been there you couldn't understand."

Wounded soldiers of D Company, 3 RAR, sent down by flying fox to jeeps waiting to transport them to the RAP.

A heavily sandbagged RAP for 3 RAR. In the foreground is an army jeep that has been converted to carry

stretcher cases.

Aeromedical evacuation in a US helicopter of a wounded Australian soldier, in a "pod" attached to the side.

Nurses

Twenty nurses of the RAAF served in Korea, assisting with the evacuation and care of the wounded. In Japan, there was a large general hospital based in Kure, which received many casualties that were evacuated by air. In Iwakuni, six Australian nurses were attached to the RAAF hospital, assisting aeromedical evacuations. Over 12,000 casualties were flown out of Korea by the RAAF medical teams, often in difficult conditions.

RAAF nurse Sister Patricia Oliver recalled:

“There were certain dangers in transporting wounded in freezing conditions in unpressurised aeroplanes … The condition of the patients was never ideal for evacuation but it was considered preferable to return them to Japan rather than have them remain in Korea any longer… On one occasion, we had to fly so high because of the weather that I became semi-conscious from lack of oxygen.”

Working conditions

Australian medical personnel in Korea often worked in very primitive conditions, where access to running water, electricity and medical equipment was extremely difficult.

It was also difficult to see first-hand the effects of warfare on men. Dita McCarthy, an Australian nurse in Kure, recalled one Australian nurse who was determined to continue her work in Korea, even though her brother had recently been killed in action there.

There were also psychological casualties. Medical personnel were sometimes called upon to help troops cope with the distress and trauma of what they faced.

Captain Don Beard, Regimental Medical Officer (RMO) of 3 RAR recalled:

“The diggers … wondered how long it would be before they might be replaced by the dwindling number of replacements. I rapidly found that my role as the RMO was more important as a counsellor than a dresser of wounds.”

Ill-health after the war was a constant reminder to some men of their time in Korea:

“The liver is never the same after a DDT bath. For all this the Digger received the basic soldier's wage, a bottle of beer in reserve for which he paid, and a thankless return home.”

Lieutenant (later Lieutenant Colonel ) Maurie Pears, MC

RAAF Nursing Sister Cath Daniel consoles 2nd Lieutenant Reg Gasson of the South African Air Force. Gasson had his toes amputated from his right foot while a POW in Korea.

RAAF Nursing Sister Lou Marshall prepares a patient for a medical evacuation flight from Korea to Japan.

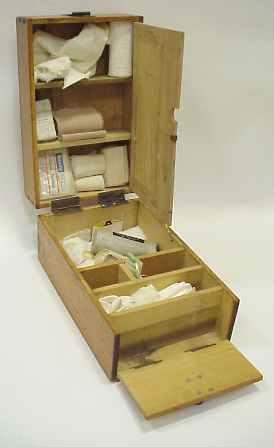

Nathalie Oldham (now Wittmann) carried this Japanese-made box for medical supplies such as bandages, antiseptics and morphine needed for in-flight treatment. She also served with a US air evacuation squadron. Wittmann and four other RAAF nurses were recently proclaimed Ambassadors of Peace by the Republic of Korea.

Captain John Morgan, 101 Australian Mobile Dental Team, treats 3 RAR soldier Private "Ned" C. Sparkes, only 1,000 yards behind the front line, June 1953. HOBJ4352