Looking back: Australians on Crete

Special Exhibition

10 June 2005 to 7 August 2005

Works of art by Michael Winters

In May 1941 Australian, New Zealand and British troops were involved in ten days of desperate fighting against German forces on the strategically important island of Crete.

Michael Winters, a Canberra-based contemporary artist, has created a series of works that offer a retrospective interpretation of the Australian experience of war on Crete. Drawing on figures from Greek mythology and the turbulent history of Crete, his prints, drawings and paintings refer to the impact of the battles, the personal experiences of the soldiers that served there, and the strength of the relationships between the soldiers and the people of Crete from the time of the battles to the present day.

Winters is an internationally recognised draftsman, painter and printmaker. His long-standing relationship with both Greek culture and the people of Crete has heavily influenced his life and work. Winters has a passion for the myths and legends of ancient Crete and incorporates symbolism from the rich history of the island into his art. It was while living on the island in 1984 that Winters was first inspired to produce a body of work that would reflect Australia’s role in the campaign. He began work on this series in 1990 when he returned to live on the island just before the 50th anniversary of the battles.

Michael Winters

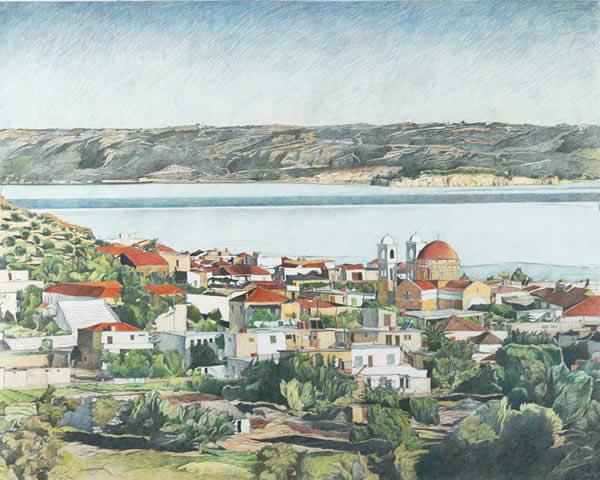

Crete, morning light, Suda Bay

pencil, coloured pencil on card

drawn in Crete in 1991

81 x 101 cm

OL00475.060

The campaign for Crete: May 1941

Dr Albert Palazzo

Historian

From 20 May to 1 June 1941, Australian, British, New Zealand, Greek and German soldiers fought a savage battle for possession of the island of Crete. At first victory was uncertain, and could have gone either way. German reinforcements tipped the scale, however, and the campaign swung against the British. The result was another evacuation by sea of defeated British soldiers, and the falling of yet another part of Europe to Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime.

The origins of the Cretan campaign lay in the preceding battle for Greece. In one sense it was a logical step in the Nazi path of conquest, yet German planners also saw the island as strategically important. They feared that British planes operating from Crete’s airfields could bomb the oilfields at Ploesti in Rumania, which were the source of most of Germany’s petroleum.

Most of the British defenders on Crete were refugees from the failed Greek campaign. They arrived exhausted, with little equipment and weapons. However, while tired, they were not demoralised and were ready to face the Germans again.

On 20 May German paratroopers and glider-borne infantry landed at four points: the airfields at Maleme, Retimo and Heraklion and the British administrative area of Cannea-Suda. At first the defenders marvelled at the German’s boldness. For nearly all, this was the first time they had witnessed an airborne invasion. But as the sky filled with descending Germans, the defenders opened fire. Entire German units were consumed in a hail of bullets and bombs, before or just after they reached the ground. A German company that floated down around Pirgos started the day with 126 men. Within two hours the defenders had accounted for 112.

The German assaults on Heraklion, Retimo and the Cannea-Suda area failed. The remaining paratroopers found themselves on the defensive, fighting for survival. At Maleme, many of the Germans met a similar fate. However, those who came down west of the airfield landed in an undefended area and arrived relatively unscathed. The struggle for Maleme became the focal point of the campaign. Despite heavy losses the New Zealanders of the 22nd Battalion stoically threw back desperate German attacks. As darkness fell they still held the airfield.

That night the 22nd Battalion’s commander made a fateful decision, one which determined the battle’s outcome. He believed that the Germans had destroyed his forward companies, and, unable to get support from his neighbouring battalions, he withdrew. The Germans soon surged forward to occupy the empty positions.

The next day the Germans began to fly in reinforcements. Sensing the danger, the British commander, New Zealander General Bernard Freyberg, ordered a counter-attack. It failed. With each arriving planeload of soldiers and heavy weapons the German strength grew. The British forces continued to resist fiercely, but on 27 May Freyberg accepted the need to evacuate.

The main evacuation point was Sfakia on the south coast. There, on the nights of 28 May to 1 June, the Royal Navy embarked most of the waiting troops. The Heraklion garrison departed from that city on the night of the 28th. The Australian defenders at Retimo, mainly of the 2/1st and 2/11th Battalions, never received the message to withdraw and surrendered on the 30th. Peace did not descend on the island with the evacuation. Instead, over the next four years the local Cretan people waged a bitter guerrilla war, which their occupiers were unable to quell.