Looking back: Australians on Crete - Defeat & evacuation

On 27 May Freyberg accepted that evacuation was necessary. The main departure point was the village of Sfakia. With the Germans in close pursuit, the army made its way across the rugged mountains that divided the island. The Australian 2/7th and 2/8th Battalions were part of the rearguard that held off the Germans. The evacuation began on the night of 28 May. Each night more ships arrived, but there was neither time nor enough ships to rescue everyone. When the final ship departed on 1 June 5,000 British soldiers remained on Crete, including the 2/7th.

The Royal Navy took off the Heraklion garrison on the night of 28 May. Discovered the next morning, the convoy was repeatedly attacked by German bombers; the Hereward was wrecked and other ships damaged, killing over 400 soldiers and sailors. At Retimo nothing could be done for the Australians. Cut off, they never received the order to evacuate. On 30 May they capitulated, and the men of the 2/1st and 2/11th Battalions became prisoners.

Many soldiers refused to accept defeat and headed into the mountains. Some were caught, others joined the resistance. The local people, such as the monks of Moni Prevali, protected many until it was safe for them to escape. Eventually, about 600 soldiers made their way to Egypt.

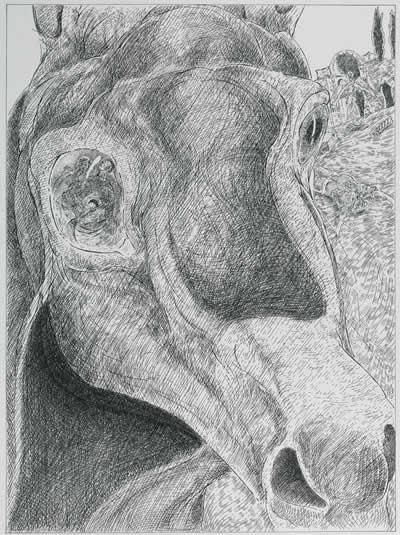

Michael Winters

Death reflected in the eye of a donkey

pen and ink on card

drawn in Canberra in 2003

50 x 36 cm

OL00475.035

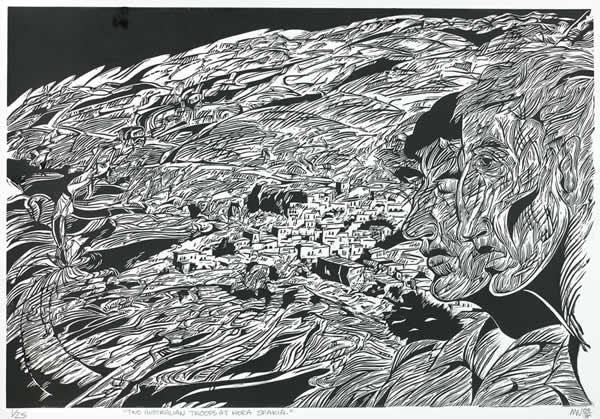

Michael Winters

Two Australian troops at Hora Sfakia

linocut on paper

made in Canberra in 2004; printed in Portland, Vic in 2004

35 x 50 cm

OL00475.014

Michael Winters

The burial of a comrade, among the vines of Crete

linocut on paper

made in Canberra in 2003; printed in Portland, Vic in 2004

50 x 35 cm

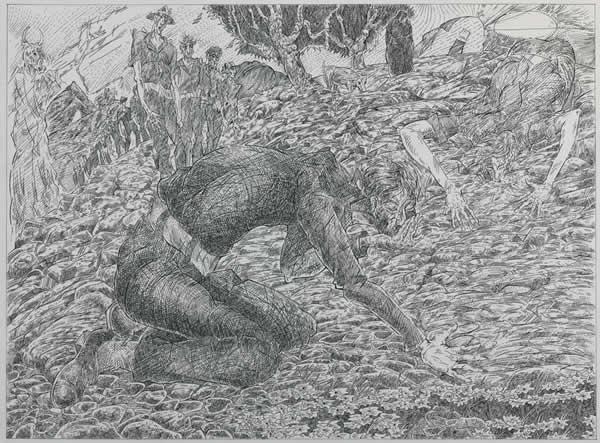

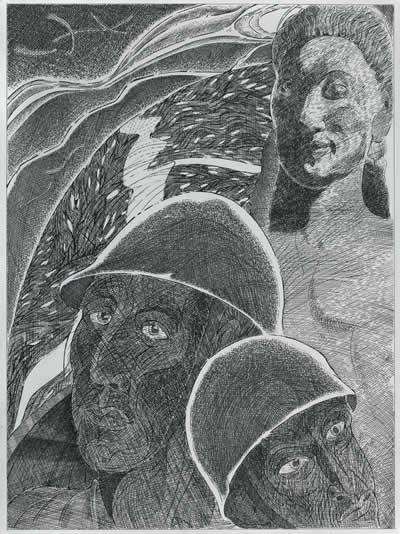

Michael Winters

Captured Australian and emblem from the Southern Cross

pen and ink on card

drawn in Canberra in 2004

50 x 36 cm

OL00475.044

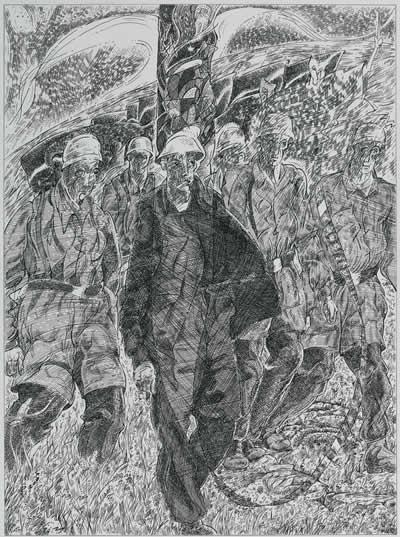

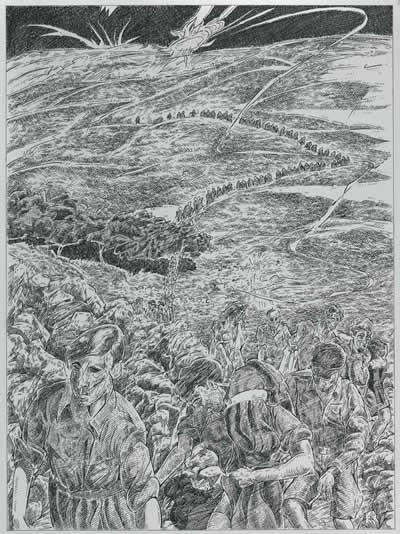

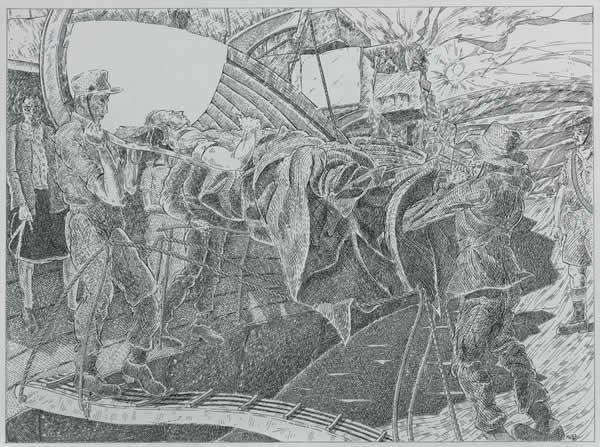

Michael Winters

Night march of the captured and a circle of the dead

pen and ink on card

drawn in Canberra in 2004

69 x 94.5 cm

In this work Winters depicts the events told to him by William Travers of the 2/1st Battalion. Travers was the Company Commander and had led his Company for three campaigns. His relationship with his troops and the respect he held for his men meant that having to surrender to the German’s was a particularly difficult experience for him. After capture, he and the other Australian soldiers were forced to march during the night to an assembly point where they were to be taken off the island. During the march they saw a circle of dead British soldiers lying at the foot of a bridge under the light of the moon.

Michael Winters

Thirst, on the retreat

pen and ink on card

drawn in New Zealand in 2003

36 x 50 cm

OL00475.029

Michael Winters

Captured

pen and ink on card

drawn in New Zealand in 2003

36 x 50 cm

OL00475.026

Michael Winters

Two of the fallen and their journey on the River Styx under the gaze of an ancient Kouros

pen and ink on card

drawn in Canberra in 2004

50.6 x 37.8 cm

OL00475.052

In Greek mythology the River Styx served as a crossroad where the word of the living met the world of the dead, known as Hades. It was believed that the souls of the dead, Gods, mortals, heroes and villains, were all transported across the river by the ferryman ‘Charon’.

Here two Australian soldiers float down the River Styx in a wooden boat. Behind them is a Kouros or youth sculpture. These stylized monumental figure sculptures, which depicted young unclothed men, are considered today to be one of the most distinctive products of Archic era, the period of ancient Greek history from approximately 650 to 500 BCE.

Michael Winters

Wounded at the church, Imvros

linocut on paper

made in Canberra in 2003; printed in Portland, Vic in 2004

50 x 35 cm

A church at Imvros was used by the Allied troops as a shelter in which to treat the wounded and the dying during the retreat.

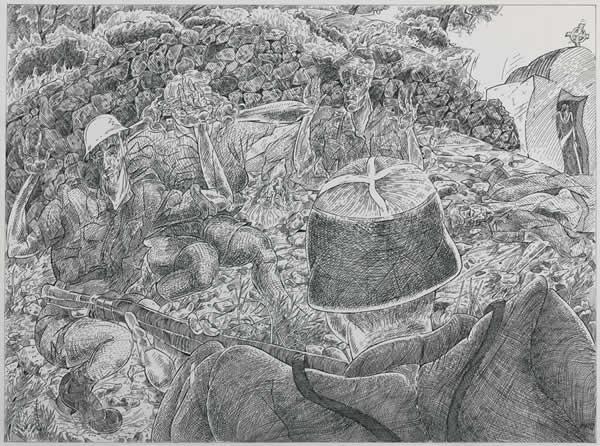

Michael Winters

Night and retreating troops amid the rocks of the Imvros Pass

linocut on paper

made in Greece in 2001; printed in Portland, Vic in 2004

35 x 50 cm

Michael Winters

Retreating troops amid the landscape of Crete

pen and ink on card

drawn in Canberra in 2004

50 x 36 cm

OL00475.042

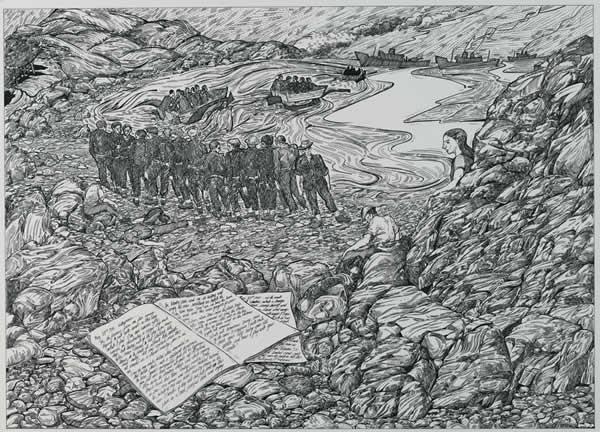

Michael Winters

A dropped diary of an Australian soldier on the beach at Hora Sfakia

pen and ink on card

drawn in Crete in 1990

37.5 x 52.5 cm

OL00475.018

Michael Winters

An escape from Crete, with blankets for sails

linocut on paper

made in Canberra in 2004; printed in Portland, Vic in 2004

50 x 35 cm

After the organised embarkation had ceased, as many as 600 soldiers were left behind on the island. Many of these men made their way back to Egypt in landing barges, fishing boats and submarines. An Australian soldier who found himself separated from the retreating Allied troops found an old, barely seaworthy boat on the coast. With no motor and no oars he decided to make a sail out of blankets sewn together with bootlaces. During the long journey he had to bind his eyes as they became inflamed by the exposure to the sun and the sea. Exhausted and parched with thirst he finally washed up on the north coast of Africa where he was found by allied troops.

Michael Winters

The escape of an Australian soldier

pen and ink on card

drawn in Canberra in 2004

36 x 50 cm

Private Stan Carroll, a soldier from Western Australia, found a sixteen foot Greek fishing boat and decided to try and make an escape. He used a piece of drift wood as a mast, a fishing spear as a boom and a piece of bamboo as the peak. To make a sail he used an old piece of light canvas which he had found in a flour mill. He set sail on the night of 11 June with the intention of sailing along the coast to find some other soldiers. However after coming under German fire at each attempt he changed his mind and set off alone for Egypt with six tins of chocolate and two gallons of water on board. On the seventh day of sailing the wind picked up and the sea became very rough. The boat slowly started to take on water and eventually broke into pieces. By this stage Carroll could see land in the distance so taking hold of the almost empty water tin across his shoulders and started swimming. It took him seven hours to reach the shore where he was later found by British troops.

Michael Winters

Wounded Australian arriving in Alexandria

pen and ink on card

drawn in Canberra in 2003

36 x 50 cm