Secret Agents across the Samichon

The river crossing had gone smoothly. The dark night and the monsoon-swollen river provided some cover to the clandestine nature of the four agents’ movements. Splitting into pairs, they made their way towards their objective, an anti-tank ditch behind enemy lines. As they reached the ditch, enemy machine-gun fire split the night apart. One agent fell dead; the other, wounded, faced being caught and killed as the enemy closed in.

The intelligence war in Korea began during the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. With the country divided into north and south zones, each side sought to destabilise the other. By 1953 agents on both sides of the wire had experienced varying degrees of success. One group in particular, the 1st Commonwealth Division’s Special Agent Detachment, had been very successful.

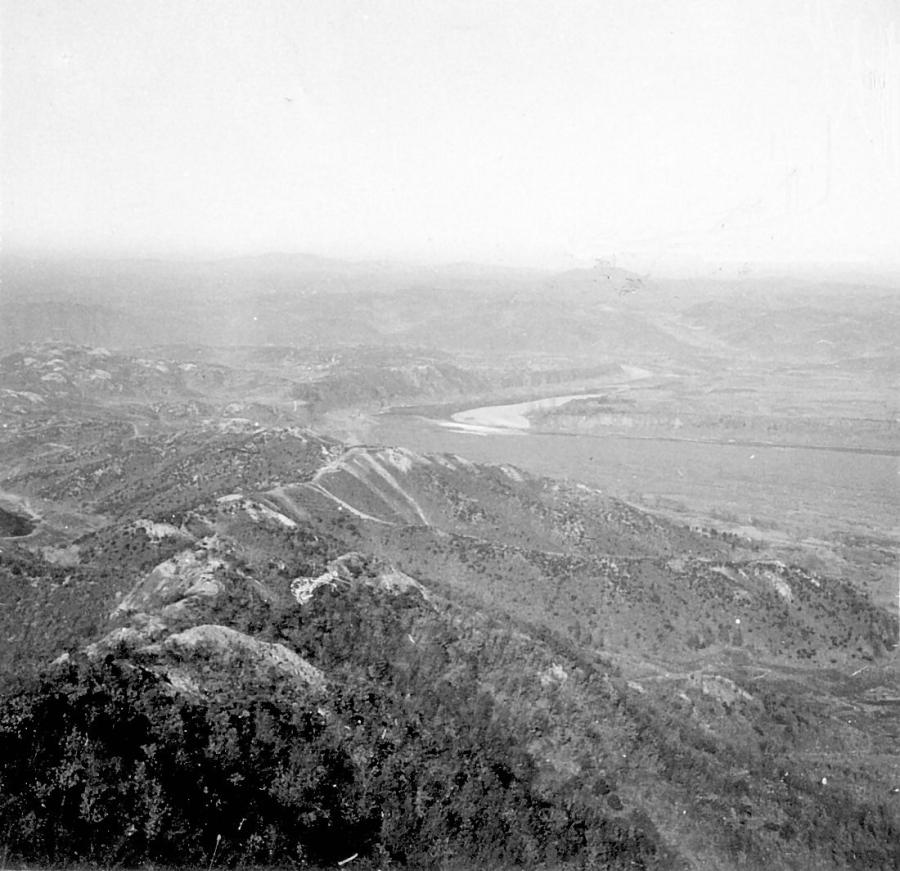

Operating in the Samichon Valley, the detachment became familiar with Chinese operations and was able to provide intelligence to United Nations Command. In the latter month of the war, the detachment was run by Australian Sergeant Arthur “Jack” Harris, who had become an intelligence operative after being wounded at Chongju in 1950, and whose war behind enemy lines would become the stuff of legend.

Prelude

Harris was born in Mildura, Victoria in July 1925 and spent his early years across the Murray River at Buronga before moving to the inner Melbourne suburb of Moonee Ponds. He worked as a labourer, fitter and turner and merchant seaman before joining the Australian Army in early 1946, having seen an advertisement for men to serve in the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan.

Arriving in Japan, he joined the 67th Battalion and became a member of its intelligence section. Over the next eight months he was promoted to sergeant and gained a good grasp of the Japanese language through interactions with the locals. Looking to formalise this knowledge, he attended a nine-month Japanese language course before returning to his battalion in July 1950, shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War. By this time his battalion had been renamed the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR). Seeking a more active role, Harris transferred to 9 Platoon, C Company, becoming a platoon sergeant.

3RAR was preparing to return to Australia and was at around half-strength when it was committed to the Korean War in late July 1950. In August, the K Force recruiting campaign bolstered the ranks by recruiting Second World War veterans into the army for three years, including one year in Korea, minimising the training effort required. By the end of the month, 3RAR was almost back to full strength. The battalion also received a new commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Green, a decorated veteran of the Second World War.

British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) members watch 3833 Sergeant (Sgt) Alfred Martin Harris, a member of the North Zone team, win the 3 mile race during a BCOF athletics meeting held at Anzac Park.

Battle of Chongju

As part of the 27th Britiash Commonwealth Brigade, 3RAR was at the forefront of the US-led advance into North Korea in early October 1950. Harris took part in 3RAR’s early actions, including the capture of a North Korean regiment at Sariwon, the battle of the Apple Orchard, the battle of the broken bridge at Kujin, and the battle of Chongju.

The battle of Chongju began on 29 October. After almost two days of fierce fighting, 3RAR had captured its objectives and was in rest positions. Harris was resting in the sun with several of his men when their idyll was broken, as he described it, by a “tall, skinny, highly agitated” American soldier who “had difficulty controlling himself as he told us there was a self-propelled gun being dug in just below our position”. With his platoon commander Lieutenant David Butler away, Harris took several men, including a bazooka team, and headed down the hill to investigate.

As he neared a ruined village at the bottom of the hill, Harris spotted movement. When he turned to shout a warning to his men, he felt a hammer blow to his left hand: “I lifted my fist and saw I had taken the bullet in the gap between my thumb and the first finger. The entry wound was tiny, but the lead had taken all my knuckles away and the exit, where the smashed bone had been blown out, was huge.” Angry about being wounded in such a manner, Harris was evacuated to the 8063rd Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) at Anju, where surgeons saved his hand.

Later that day a North Korean self-propelled gun fired into 3RAR’s positions. Five rounds hit the forward slope of the hill occupied by 3RAR; the sixth cleared the hill, hitting a tree and exploding. Around 40 men from the battalion were in the vicinity, but the only one hit was Lieutenant Colonel Green. Wounded by shrapnel from the explosion, he was evacuated to the MASH at Anju, where he died on 1 November.

By January 1951, Harris was in Australia, undergoing intense physiotherapy. Despite the lack of metacarpal bones, he regained movement in his fingers, but his career as an infantryman was over. Having transferred to the intelligence corps, he attended a Chinese language course at the Royal Australian Air Force School of Languages before being seconded to the Australian Secret Intelligence Organisation (ASIO).

In January 1953 Harris was sent to New Guinea to identify communists among the local Chinese population, but without success. Bored and frustrated, he wrote to the head of Army Intelligence, volunteering for a second tour of duty in Korea, and was soon back in the Land of the Morning Calm.

Seconded to a US-led Interrogation of Prisoners of War Team, Harris found this unit suffering from poor morale and discipline due to a lack of prisoners and direction, so he organised a transfer to the 1st Commonwealth Division’s Special Agent Detachment. Welcoming Harris to his new position was the man he was to replace, Second World War veteran Staff Sergeant Clifford Jackson DCM MM. An original member of the unit when it formed in 1951, Jackson had established safe houses, hired and trained agents – including a good number of former South and North Korean soldiers and civilian refugees – and undertaken patrols and operations with them.

Harris’s new home was in a ruined village near the Imjin River. A sign had been erected on the road in warning would-be visitors that the village was the site of a smallpox outbreak. Despite its dilapidated appearance, the village was a hive of activity. Harris and his agents trained with Chinese weapons – particularly the Chinese variant of the Russian PPSh-41 sub-machinegun, grenades and knives – and wore Chinese uniforms. Aside from Harris, they could blend in behind the lines with little effort.

Harris quickly came to rely on two agents: Pak and Lim. Pak had seen his father and sister murdered in front of him by a North Korean political officer and had barely survived after being shot twice and brutally beaten. Retrieved by British troops, he recovered, joined the South Korean army and was wounded in action. While in hospital, he was recruited for the Special Agent Detachment by Lim.

Lim, the detachment’s senior agent, was an older man, thick-set, strong and level-headed. He had served in the Japanese puppet army in Manchuria. After witnessing the torture of a woman by Japanese soldiers, he killed several of them and deserted to the Chinese guerrillas. Captured and tortured by the Japanese, he was released after convincing his captors that he was mute. Returning to Korea after the war, he served in the South Korean army before being wounded and discharged, and then recruited as an agent.

Harris wasn’t going to ask his agents to take risks that he would not take himself, so he accompanied his agents across the Samichon at the start of every operation. He made his first crossing in March 1953 and got to know the landmarks and hazards as he and his agents travelled behind Chinese lines, observing and reporting on troop movements, stores, and weapon emplacements.

Haramura, Japan. 1950-09-06. Troops from "C" Company, 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR), during a training exercise to carry out an assault on a hill. Left to right: 3/833 Sergeant A. M. Harris, Platoon Sergeant relaying a message to 5/1263 Private G. W. Lobb for onward transmission to Officer Commanding by Walkie Talkie radio communication.

Final offensive

The intelligence gathered by Harris and his agents pointed to the build-up of a final Chinese offensive, which materialised in the last days of the Korean War. United States Marines adjacent to Australian positions on the Hook bore the brunt, but the men of 2RAR – including Harris’s former platoon commander, Captain David Butler – endured intense bombardments and probing attacks.

The Korean War came to a tenuous halt with the signing of the armistice at Panmunjom on 27 July 1953. When it came into effect, Harris was forced to disband his unit. Having bid farewell to Lim and the other agents, he was briefly posted as a Chinese interpreter to the United Nations Command Military Armistice Commission at Panmunjom, after which he returned to Australia.

He discharged from the army in May 1954 and taking up an offer from the head of the organisation, went to work for ASIO. One of his first jobs was guarding Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov, Soviet defectors who were giving evidence at an Australian Royal Commission into espionage. He worked for ASIO, predominantly in Hong Kong, until 1965 when he took up a senior post with the Australian retail group Myer. While successfully running Myer’s operations in Asia, Harris completed a master’s degree and a doctorate. The Tall Man, a fictitious account of his time with the Special Agent Detachment in Korea, was published in 1958, followed by Grains of Sand, a fictitious account of the rescue of Lieutenant Colonel Carne. He later wrote two autobiographical works: Only One River to Cross and Seize the Day. He returned to Australia in the mid-1980s with his wife, Julie, and children, Stephen and Joanne, and for many years remained active with the Oriental Society of Australia.

Australian soldiers, probably of the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (2RAR), stand above their front line trenches at the Hook feature. One of a series of photographs taken by the Australian Mr Douglas (Doug) Bushby in his capacity as a UN accredited War Correspondent.

The Hook and the rescue

On learning that the safe house operator at Namsong-Dong had vital information to pass on, Pak and Harris travelled by night for three days, coming close to being discovered on several occasions. As they used waterways to sneak into the village, Chinese soldiers passed above them. On reaching the safe house, Pak accompanied its owner to plot Chinese positions and the build-up of stores, which pointed to an impending offensive against the Hook. Details were plotted onto Harris’s map, and the pair made their way to pass the intelligence to Commonwealth Division headquarters.

The Chinese launched one last direct attack on the Hook, which was held after fierce fighting by the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. In April Operation Little Switch, an exchange of sick and injured prisoners, took place at Panmunjom. Intelligence from returned British prisoners revealed the location of Lieutenant Colonel James P. Carne DSO, who had been captured during the battle of the Imjin River. Carne was reported as being kept in solitary confinement and, like many other prisoners, badly mistreated.

A plan was hatched to effect his rescue, and Harris was tasked with ensuring a route through Chinese lines remained open. Two British operatives arrived from England and Harris spent time training with them and a small team dedicated to the rescue.

On the night of 2 July 1953, Harris journeyed across the Samichon with Pak, Lim and Chet. A fourth agent, Soong, remained on the opposite side of the river to await their return. Once the men had crossed the fast-flowing river, the unit divided into pairs and headed towards a Chinese anti-tank ditch around 1.5 kilometres behind the front line.

As Harris and Pak reached the ditch, Pak whispered an urgent warning – “Machibuse!”, Japanese for “ambush” – and pushed Harris down; it was the last thing he said. Harris barely had time to register it before a machine-gun opened fire. He recalled seeing “bullets come in a circular red pattern and hit Pak in the chest from a few feet away. I heard him sigh ever so gently. I knew he was dead.” Harris took cover behind Pak’s body as a concussion grenade went off nearby, followed shortly after by a second grenade, whose shrapnel wounded Harris in the right hand and thigh. He responded by throwing two No. 36 Mk I Mills grenades to keep his enemy at bay. Realising the other two agents remained undetected, Harris returned fire with his pistol to keep the enemy focused on him. He released the safety catch on his PPSh machine-gun and threw it towards the Chinese. As it hit the ground, it fired the entire magazine. Facing capture and certain death, Harris withdrew, entered the Samichon, and let its current carry him to safety.

Lim and Chet returned a short time later and reported that the planned route to bring Carne out of North Korea was compromised. The rescue attempt was abandoned. Carne was released in September 1953 and was awarded the Victoria Cross the following month for his courage and leadership during the battle of the Imjin. Harris was awarded a Military Medal for his courage over his 11 trips behind enemy lines.