“The best thing the division has done”

On 9 April 1918, the German Army launched Operation Georgette, a major offensive against the British positions in Flanders. This was the second operation of the German Spring Offensive, after the failure of Operation Michael further south. A key goal for the Germans was the capture of the strategic railway hub at Hazebrouck. The attack enjoyed some initial success against British and Portuguese units. The British withdrew from Messines and the Passchendaele Ridge, which had been taken at such a high cost the previous year. The British and French were able to move up reserves rapidly, including the 1st Australian Division, and the offensive was stopped outside Hazebrouck. Operation Georgette had been another costly failure for the Germans, who chose to make a second attack on Amiens soon after.

The 1st Australian Division, which had played a large part in the defence of Hazebrouck, now controlled the front line outside Strazeele, to the west of Hazebrouck. This new front line had little in common with the vast, well-made trench systems of 1916. It was made up of strong points that could provide mutual support to one another. The villages, still occupied by civilians before the offensive began, were damaged but not pulverised, and the vegetation still provided ample cover. Crucially, the German army the Australians faced was exhausted, poorly supplied and stretched beyond its limits.

Looking towards Merris the month before it was taken, the availability of thick vegetation for cover is clear

One of the key villages just in front of the Australian line was Merris. This small village lay about eight kilometres from Hazebrouck. Through aggressive raiding, known as peaceful penetration, the Australians were able to push the Germans back to new defences just outside the village, which made the village the front line.

On 14 July the 10th Battalion once again manned the front line outside Merris. They had been involved in moving the line closer to the village the previous month, with Corporal Phillip Davey earning the Victoria Cross during these actions. The battalion decided to keep up the pressure, and on 22 July attacked the flanks of the village with two companies. The attack was successful in demonstrating the weaknesses in the German defences, but German artillery forced it to withdraw.

The British XV Corps, to which the 1st Australian Division was attached, began to consider an attack on the Oultersteene ridge with three divisions. The capture of Merris was needed as a preliminary step. The 10th Battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Maurice Wilder-Neligan, was ordered to take the village on the night of 29– 30 July.

Lieutenant-Colonel Maurice Wilder-Neligan, Commanding Officer of the 10th Battalion

The plan

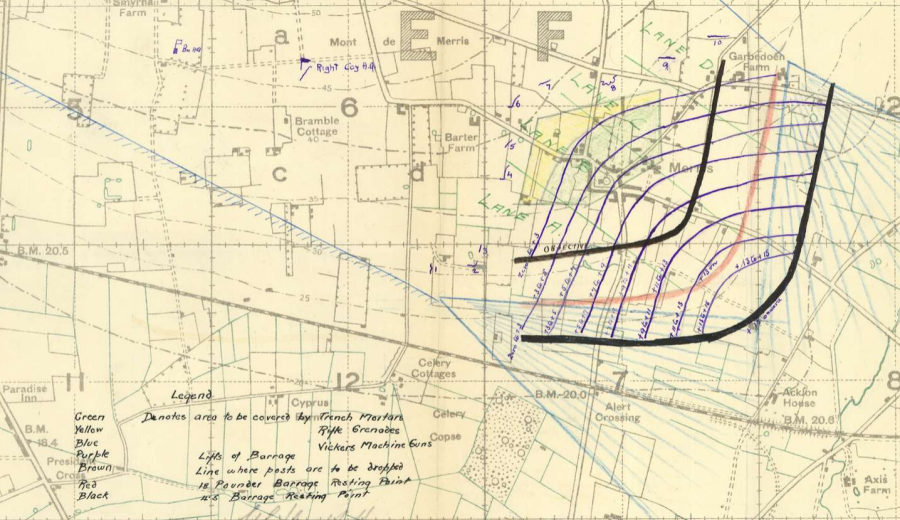

Wilder-Neligan conceived a plan that drew upon the tactical experience of the British Army over almost four years of war. It was to involve a simultaneous assault by two companies, one from the north-east and the other from the south-west. The companies would advance under a creeping barrage, while being careful to stay clear of a barrage that was simultaneously landing on the village. While moving around the flanks of the village, they were to leave platoons at strategic points. These platoons would dig in and prepare for attack from both sides, for which they were each provided a second Lewis gun. Overall the attacking force numbered about 160 men.

Artillery support was to be provided by four artillery brigades, two Australian and two British. The 18-pounders and 4.5-inch howitzers would provide a creeping barrage, moving through the village and stopping behind the objective line 15 minutes after commencement. Light mortars and rifle grenades from the two supporting companies and a battery of 4.5-inch howitzers would maintain a barrage on the village itself. Improvements in the use and accuracy of artillery meant that the infantry would be able to advance around the village, while the bombardment of the village did not have to stop.

18 pounder of the 12th Army Brigade in an improvised shelter the day after providing Fartillery support to the 10th Battalion

An hour and five minutes after the operation had begun, the guns firing into the village would stop. A special platoon would then have 55 minutes to clear the village of Germans. A signal to the platoon to withdraw from the village would be made by five minutes of incendiary rounds being fired into a nearby house. The barrage on the village would then continue.

Two companies of Vickers machine-guns, with 14 guns, were to provide a machine-gun barrage firing down the flanks of the objective, maintaining a rate of 100 rounds per minute until the objective had been taken. The guns would then stand ready to provide assistance if an SOS flare was fired.

Map showing the plans for artillery and machine gun bombardment of Merris

Attack

By midnight on 30 July, A Company was lined up south of Merris at an old post, while B Company lined up in a thick wheat crop to the north, ready for the attack to begin 15 minutes later. While moving into position four German shells landed on 5 platoon of B Company. Lance Corporal Frank Nelson was killed and 10 others were wounded, including the platoon commander, Lieutenant Graham Smith, and two NCOs. This platoon was to have been the unit that linked up with A Company behind the village; but as it had taken casualties, it was the first platoon to form a post during the advance.

At zero hour the artillery bombardment began. They had registered their guns on Merris church the previous day in preparation for the attack and were able to hit their targets accurately from the start. After using a creeping barrage that lifted roughly every three minutes for 15 minutes, they maintained a steady barrage in front of the assaulting forces. British heavy artillery shelled behind the final objective of the Oultersteene Road, while the 101st Battery of the 1st Field Artillery Brigade was tasked with shelling the town of Merris itself.

The attacking companies moved forward immediately at zero hour, each platoon advancing with two men covering each flank from a few yards away. As planned, each company left platoons at intervals along the way around the village. These platoons immediately dug in and positioned one Lewis gun towards the village and the other towards the new German front line.

After only 25 minutes the two companies joined up to the east of Merris. They had experienced only minor resistance, with small parties of Germans surrendering after being hit by bombs and Lewis guns. They now surrounded the village, which had been under constant bombardment the entire time. Lieutenant Pennington, who commanded one of the two platoons that joined up behind the village, fired a flare to signal their success.

After the village was surrounded and the defensive posts were dug in, patrols were sent out to capture enemy forces and assist the other posts when they were under attack. Sergeant William Faint, with five men, patrolled in front of the newly established posts. They used bombs (grenades) to clear out German positions, and after killing a number were able to capture 17 Germans and a machine-gun. Sergeant Ernest Mann and Private Donald Winter noticed an enemy force setting up in a wheat crop in front of their position. They crept forward, and after throwing a few bombs were able to capture 15 men and a machine-gun.

Lance Corporal Daniel Melville and Private Albert Bache were manning a Lewis gun in their post when they believed they were being attacked by 30 Germans. Australia’s Official War Correspondent, Charles Bean, suggests these men actually ran into the post by accident while trying to retreat. This is certainly a possibility, considering the general disorder of the Germans at the time, but it would have been impossible for the Australians to know this. A firefight ensued and their Lewis gun was put out of action, so the two men crawled into a position to attack their attackers with bombs. After taking them by surprise, Melville and Bache were able to kill a number and capture 21 men and two machine-guns.

A German machine-gun opened fire on one of the posts. Private Horace Beaton, who was in the next post to the right, saw this and crawled forward with one man. They were both discovered and fired upon, but they rushed the machine gun nest, killing four men and capturing 7 others as well as the machine-gun.

At 1.20 incendiary rounds began to be fired into Merris itself and continued for five minutes. This was a signal to a special platoon (led by 2nd Lieutenant Hartley Edwards and made up of batmen, orderlies and cooks from battalion headquarters) that the bombardment on the village would stop for one hour. They started from the north along the road leading into the village and worked their way south. The men of this platoon were provided with electric torches and instructed to clear the Germans out of the houses and cellars in the village.

It was dark, and the constant bombardment from 4.5-inch howitzers, Stokes mortars and rifle grenades had done significant damage to the village. Luckily many of the Australians had spent time drinking in Merris before the German offensive and were able to guide the others. To start with, the only inhabitant of the town they found was a cat, which fled at the sight of them. The Germans they did encounter surrendered immediately. Eventually they reached a building covered by three German dugouts; these refused to surrender and had to be neutralised with phosphorus grenades.

While the special platoon was clearing out the village building by building, the two companies holding the line in front of the village began to move forward and clear out the Germans from their old front lines. When the men of the special platoon saw the previously arranged incendiary rounds falling on Acklow house on the outskirts of the village, they withdrew from the village. The clearing out of the village had been successful, with 5 machine-guns and a large number of prisoners taken. But it was not complete, and prisoners were still coming from the village well after daybreak.

The attack did create some confusion on both sides. At about 2 am an Australian runner from the second post in the north was sent back for water. He accidentally ran into a German post at Garbedeon farm at the northern edge of the attack – but managed to convince the 31 occupants to surrender. An hour later a German officer, completely unaware of the location of the Australian positions, walked right up to a Lewis gun and surrendered immediately after realising his mistake.

While the two attacking companies maintained their new positions, carrying parties from the two companies manning the old front lines brought supplies up to them. When Corporal Alfred Dunne and Private James Sincock from D Company went to get supplies at about 4.30 they took the wrong road and hit the main German line. Dunne was wounded, but managed to work his way back to the unit; shortly after informing them that he did not know what had happened to Sincock, Dunne died. Sincock had been captured by the Germans.

At 9 am Lieutenant Drew Sharland and Sergeant Charles Williams crept forward to attack a German machine-gun that had been causing problems. As they approached, Sharland shot one man in the head; after a few others had been killed by bombs, the post’s remaining seven occupants surrendered.

German confusion continued as dawn broke. At about 10 two German runners ran into Lieutenant Pennington’s post. They had come from the village and were completely unaware that they were surrounded. The runners’ message, according to Brigade diaries, stated that the British had attacked and the situation was obscure. Sergeant Faint in the second post on the north side went out with one man to assist the third post, which was being sniped at. He found the German post and shot one man and captured another five, taking them to the third post to surrender, before returning to the German post to souvenir the machine-gun that had been left behind.

Sergeant William Faint received a bar to his Military Medal for his bravery during the attack on Merris

From the outset the Australian plans had called for strong preparations to stop any counter-attack that the Germans might launch. Each platoon had been issued with a second Lewis gun for this purpose, while the Vickers machine-guns and artillery were tasked with standing by to counter any German attacks. But none came. Three German companies had been tasked with launching one, but the fire from the Australians was so powerful that the attack was called off almost as soon as it had begun. Lacking significant reserves in the area, the Germans chose not to launch any more counter-attacks.

Aftermath

The attack on Merris was an impressive success. It was testament to the thorough planning and coordination undertaken by Wilder-Neligan and his staff. Throughout the entire attack, 3rd Brigade Headquarters were kept up to date with any changes to the situation. So good was the planning that part-way through the attack the Australians on the front line were able to enjoy a hot meal, which had been brought up in the early hours of the morning.

Not only had the village been captured and the line straightened, but four officers and 175 other ranks had been captured. Overall, German casualties for the night were at least 280. This amounted to three companies almost completely lost. The 10th Battalion casualties were comparatively light, with 48 men wounded and 11 killed. The German regiments holding Merris were the 14th and 140th Infantry Regiments, both of the 4th Division. These units had arrived in the line only on the night of 28 July, after several weeks of rest and training behind the lines. They had been expecting a relatively quiet sector.

Bean visited the 10th Battalion on the day of the attack. Later in the afternoon he went with Major General William Glasgow, who had taken command of the 1st Australian Division a month earlier, to the village of Meteren, to the north of Merris. From there Bean was able to sketch Merris and the land captured during the night. On their way up they met Brigadier-General Knox, from the General Staff of XV Corps, who said of the attack that morning, “That operation your fellows did last night is the best thing the division has done since it has been up here.”

A group of 10th Battalion non-commissioned officers the day after the attack E02795

The night after the attack, the 10th Battalion was relieved by the 8th Battalion and the 10th moved back to Hondeghem, north of Hazebrouck. Bean once again visited the unit, photographing the trophies taken during the attack on Merris. He also photographed a runner, who had been selected by Wilder-Neligan, and took his entire uniform for the Australian War Records Section. Bean failed to record the name of the soldier, but it is possible that it was Private Horace Beaton, who had captured a machine-gun and seven Germans, as well as running messages and supplies throughout the morning, later receiving the Military Medal for his bravery. Unfortunately, the photographs were double exposed; only the helmet and rifle remain in the Australian War Memorial’s collection.

A 10th Battalion runner, photographed by Charles Bean, shortly before his uniform was collected

For his planning and command of the operation, Wilder-Neligan was awarded a bar to his Distinguished Service Order. The two company commanders, Captains Hurcombe and McCann, received the Military Cross, as did three of the platoon commanders. Twelve soldiers of the battalion received the Military Medal for the attack.

The 1st Australian Division was withdrawn from Flanders and joined the other four Australian divisions to participate in the offensive launched near Amiens on 8 August. With Merris captured, the British launched their offensive on the Oultersteene ridge on 18 August. It was a success; the following month the British, Belgian and French armies launched a massive offensive in the Flanders area, which contributed to the Hundred Days Offensive that ended the war.