1993: year of the peacekeeper

A soldier smashing his radios to avoid them falling into “enemy” hands. An officer sitting through long meetings with a traditional council of elders. A woman doctor dying in a plane crash in a remote land of rocks and sand. These are a few of the many stories that came out of one year of Australian peacekeeping: 1993.

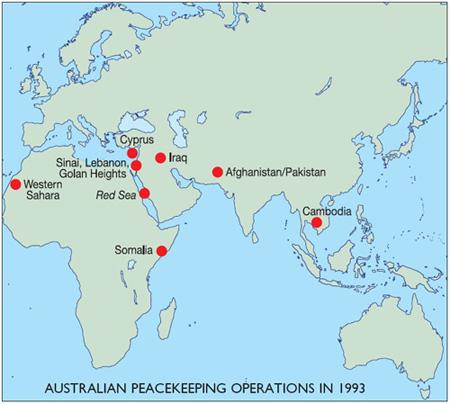

Ten years ago Australian soldiers, sailors, airmen and police were spread around the globe, from the lushness of tropical Cambodia to the harsh aridity of Somalia on the east coast of Africa; from Western Sahara to Afghanistan, with Cyprus, southern Lebanon, the Golan Heights, the Sinai and the Red Sea in between. They were not fighting a war, yet in every case war was the reason they were there.

Australian peacekeepers have been in the field since 1947, but for many years the numbers were small, most being military observers or police. With the arrival of Gareth Evans as Minister for Foreign Affairs in 1988, and the end of the Cold War the following year, the pace began to quicken. Suddenly Australia was sending a contingent of 300 engineers to Namibia, and providing ships to enforce United Nations sanctions against Iraq.

Australian soldiers helping with crowd control during the distribution of aid at a village in the Somali countryside.

There was great optimism about what the United Nations, and the international community generally, could do to promote peace, now that every conflict no longer had to be viewed through the prism of Cold War superpower rivalries. People really believed that a “new world order” had arrived. Australia was ready to do its bit: for a few months in 1993 there were more than 2,000 Australian peacekeepers in the field, many more than ever before.

Some were in operations which had been going for years, even decades. Australian military observers had been in Israel, Syria, Lebanon and Egypt since the 1950s; police had been in Cyprus since 1964. In Afghanistan, Australian sappers were about to be pulled out of a mission helping returning refugees avoid being blown up by landmines. In Western Sahara, Australian signallers were supporting an operation which was meant to culminate in a referendum on the territory’s future (the politics of the situation mean that it has still not been held). Some Australians were helping in the search for weapons of mass destruction in Iraq; another was serving as military adviser to a conference on the former Yugoslavia in Geneva.

But the two big operations that year were in Cambodia and Somalia, and in each case Australia played a distinguished role.

In the 1970s Cambodia first became collateral damage of the Vietnam War and then was ripped apart by one of the most appalling genocides of the 20th century, as the Khmer Rouge regime under Pol Pot inflicted a gruesome form of doctrinaire rural socialism on the country. A million Cambodians – an eighth of the population – were executed or died from overwork, starvation and disease. A Vietnamese invasion overthrew Pol Pot, but civil war continued until a peace agreement, which Australia had played a significant role in helping to broker, was signed in Paris in 1991.

Australia played a major role in the United Nations peacekeeping operation that followed. The Force Commander of the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) was an Australian, Lieutenant General John Sanderson. The main Australian contribution to the body of UNTAC was the 500-strong Force Communications Unit, made up of signallers drawn from all three services and also including New Zealanders. The signallers were working in a country whose communications infrastructure was largely destroyed. As a result, they were soon spread across the country, often in isolated positions. There might be ten at a sector headquarters, three in a provincial capital, but on a border control post a single signaller might be working with three or four unarmed military observers.

One such was Gunner Trenton Prince. In August 1993 Prince was on a post on the Thai–Cambodian border when the Khmer Rouge started shelling it. Smashing his radios with a screwdriver to avoid them falling into Khmer Rouge hands, Prince joined his observer team in beating a strategic retreat. They could not go far as the surrounding roads had been mined, and ended up as captives of the Khmer Rouge for eight hours. Prince had kept a hand-held radio, but whenever a call came through from headquarters trying to find out what was happening, he would get a kick or a punch from a young Khmer Rouge soldier.

Whatever the temptations, the Khmer Rouge soldiers did not want to kill a group of United Nations peacekeepers in cold blood. So, in the end they allowed the group to be evacuated into Thailand by local Thai soldiers (who seemed to Prince to be acting more or less in concert with the Khmer Rouge). Two days later Thailand allowed UNTAC to send a helicopter to pick them up.

The highlight of the United Nations’ work in Cambodia was the election of May 1993. Observers were deeply moved as 90 per cent of Cambodia’s registered voters braved monsoonal rains and the threat of violence to vote in their first free election.

Somalia was a very different story. Somali society was based around a multitude of extended kinship-based clans; at one stage the country enjoyed a parliamentary democracy with 64 political parties. In the 1980s, under dictator Mohamed Siad Barre, opposition to Barre by rival clans led to a reign of terror in which thousands died. In 1991 Barre was expelled from the capital, Mogadishu, and the country fell into chaos and anarchy. Three hundred thousand Somalis died of famine, while young thugs riding “technicals” – battered utilities with a machine-gun mounted on the back – stole humanitarian aid before it could get to those who needed it.

A United Nations operation in Somalia had included some Australians; but in January 1993 a much larger Australian contingent, a 1,100-strong battalion group based on 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR), joined a US-led operation to restore security to Somalia. The operation was known as the Unified Task Force (Unitaf), and its role was to create conditions to allow aid agencies to deliver aid to the victims of the famine; after that, Unitaf would hand the situation back to the United Nations.

The Australians were allocated the Baidoa Humanitarian Relief Sector, 17,000 square kilometres centred on the town of Baidoa in south-western Somalia. Taking over control of Baidoa from the US Marines, the Australians found a town where the buildings had been stripped and rubbish and wreckage littered the streets. Gang warfare was endemic: shootings and beatings happened every night. Aid workers lived in fear of their own hired gunmen. Around the town there were villages of refugees living in humpies made of twigs and grass and plastic bags or cardboard.

The Australian infantry set to work to impose their authority on the town, patrolling intensively on foot and by vehicle, talking to people and getting to know where the arms caches were. They made a serious attempt to reduce the number of weapons on the streets. In the countryside they patrolled, protected aid convoys, and on occasion conducted cordon-and- search operations of suspected bandit villages.

Somalia was a peace enforcement operation, meaning that a high level of force could be used when justified. On one occasion a patrol, caught in an alley in Baidoa under automatic weapons fire from the windows of a building, fired a 66-millimetre anti-tank rocket into the building to quell opposition. On a number of occasions, Australians killed Somalis in firefights.

But the operation remained fundamentally one of peacekeeping. Increasingly 1RAR commander Lieutenant Colonel David Hurley found himself drawn away from his battalion to a role in effect as Baidoa’s military governor; from the start, he knew that the politics would be the hardest part of the job. Early on he wrote:

This is a frustrating little war we have over here. No enemy but people shooting at our patrols. Elders wanting us to help them but not providing information. You can’t trust anyone to be telling the truth.

To the Somalis Hurley was the Australian chief elder, and the result was long meetings discussing how to set out to rebuild the political, judicial and civil life of the town. Much of this got bogged down in clan rivalries, but the Australians made a real attempt to set up fair and impartial institutions which would survive their departure.

In May 1993 the Australians departed Baidoa, leaving behind a situation considerably calmer than that when they arrived. Peacekeeping operations are never entirely successful, but they rarely entirely fail, either. Although Somalia ended as a failure for the United Nations, in their few months in Baidoa the Australians had saved lives and had given support to those Somalis interested in peace. This was a story repeated at many places around the globe in Australia’s year of peacekeeping.

Two deaths

Only ten Australians have died while serving on peacekeeping operations: two were in 1993. Early in the evening of 2 April 1993, 21-year-old Lance Corporal Shannon McAliney was going out on patrol when another soldier handed him his Steyr rifle to hold. The rifle discharged and the bullet hit McAliney in the stomach at point blank range. Although he was wearing a flak jacket, McAliney suffered massive internal injuries and, despite efforts to treat the wound, he died later that night.

Major Susan Felsche was the medical officer with the Australian contingent to Minurso, the United Nations operation in Western Sahara. Based at a camp of tents at the southern sector headquarters at Awsard, surrounded by sand and rocks, she would fly out to visit sick and injured members of the force and to conduct clinics for local people. On 21 June 1993, a Pilatus Porter aircraft crashed on take-off from Awsard, killing three of the crew, including Felsche. She was the first Australian woman to die on overseas operations since the Second World War.

The aircraft in which Major Susan Felsche was killed when it crashed on takeoff in June 1993.