Life at the Dat

From 1966 to 1971 most Australian soldiers in Vietnam formed a task force which ranged across the province of Phuoc Tuy, seeking out an elusive and ultimately unbeatable enemy. The task force was supplied by sea at the port of Vung Tau, but it conducted its “operations”, as the army nicely called them, from Nui Dat, near the centre of the province. For many Australian soldiers “the Dat” was more than a military base. It was also their temporary home.

The Dat sprawled out from a low hill and by a major road which bisected Phuoc Tuy from north to south. By 1969 it housed 5,000 soldiers, and its defoliated perimeter of barbed wire was 12 kilometres long. Rubber trees provided useful shade across the base. Snakes, almost as plentiful, were less welcome, as was the constant noise from frequent landings and takeoffs by aeroplanes and helicopters and intermittent artillery and mortar fire in support of operations.

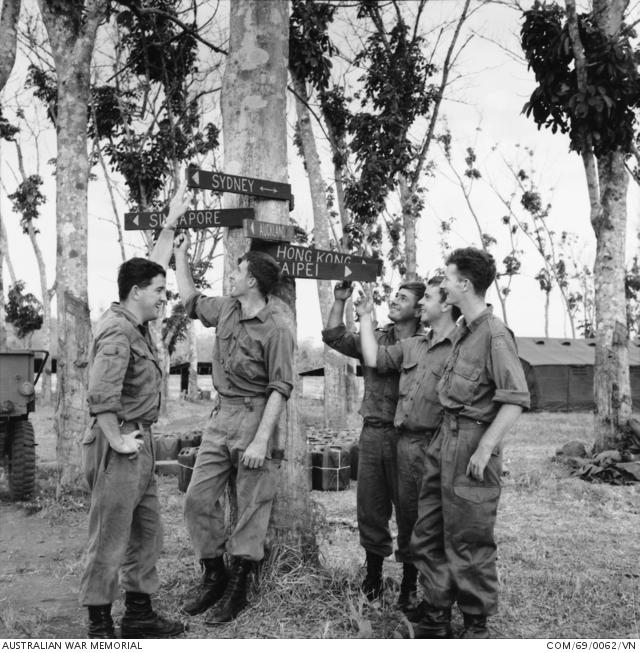

Signs of life. Directions to Sydney, Singapore, and elsewhere on a tree at the Eagle Farm helipad at Nui Dat.

Large units at the base lived in miniature villages. An infantry battalion might have its own canteen, store, post office, cinema, helipads, Salvation Army tent and chapel. Inside their own tents, soldiers might have chairs and furniture made from artillery and mortar boxes, and normally expensive stereo equipment bought cheaply from the US Army’s American Post Exchange, or PX. Latrines at the Dat were basic but comfortable, at least compared with making one’s own arrangements in the field, but they presented their own perils. “ Tonight after work,” one soldier recorded, “ someone let a smoke grenade off down the chimney when the house was full. It was really funny to watch five blokes exit quickly in a cloud of yellow smoke as they pulled up their strides and at the same time tried to wipe watering eyes.”

Combat soldiers at the Dat were either resting between operations, patrolling the perimeter, or standing ready to reply to an attack. But most men permanently stationed at the base were support troops, ranging from mapmakers to pay clerks. Much of their work simulated civilian life: painting and panel-beating, road-laying and cake-making, fixing televisions and filling tooth cavities. Not that war was far removed from their lives. Looking out from his tent, one mechanic could watch some of the bunkers that helped defend the base from attack. Like most other soldiers he would grab his rifle whenever something, usually an animal, set off one of one of the mines planted to help secure the base.

Stereos, radio broadcasts and especially mail deliveries at the Dat allowed soldiers to connect with Australia, their families and their communities. “Few moments back in camp could compare with receiving mail,” one battalion history recorded. It might come in traditional letter form, or on cassette tape. Hearing a loved one’s voice paradoxically dissolved the distance between Vietnam and Australia and yet reinforced it. Mail included parcels as well, sometimes from the Australian Forces Overseas Fund. These were valued not only for what they contained but also for suggesting that support for the troops back in Australia outweighed protests against fighting in the war. “Your efforts more than neutralise those of the ‘noisy minority’,” one soldier wrote to the fund.

Life at the Dat was, naturally, regimented. A day typically began at first light with patrols of the perimeter, a flag raising and the first of two “paludrine parades” at which soldiers took preventive medicines against malaria. Breakfast, usually including eggs, came around 7.30, followed by inspections, briefings, or several hours of work. Lunch, often cold meat and salad, was followed by more work. Around 4.30 the recreation rooms and the wet canteen, where alcohol could be purchased, would open. After dinner, which was often a barbecue, the flag was furled, sleeves were rolled down as further protection against mosquitoes, the perimeter was patrolled again, and movies might be shown.

Movies were popular. “They’re not too bad,” one soldier commented on arriving at the base. “Some of them are released here before they hit the screens in Australia and the States.” He judged Roger Vadim’s Barbarella, starring a young, scantily-clad Jane Fonda, to be “a bit rare”, but at least it gave his comrades a laugh. Concerts at Luscombe Bowl, a natural amphitheatre at the end of the base’s main airstrip, were even more popular, especially when given by entertainers from Australia like Johnny O’Keefe or Normie Rowe (who, as a National Serviceman in 3 Cavalry Regiment, was already in Vietnam), or by any woman. A good concert made the war seem to disappear for a while. Then again, so did many aspects of life at the Dat. One night work at the command post was interrupted by a phone call from some soldiers objecting that the “image on our TV set in the boozer isn’t good”, and wanting to know whether “this was general throughout the task force”.

Entertainer Johnny O’Keefe and members of his 1969–70 touring party on stage at Nui Dat.

Distractions like this were inevitable, even vital, for soldiers at war. Perhaps only the distraction offered by alcohol threatened morale as well as bolstered it. Beer was supposed to be rationed to two cans per day, but mountains of cans rose spectacularly, especially after a long operation was over. Accidents and fights resulted, occasionally with fatal consequences.

When the theft of a bugle given to an officers’ mess distracted some soldiers at the Dat for at least a day, one officer commented wryly that “one can take consolation from the fact that if things like this can cause so much fuss, we must be winning the war.” But Australia and the United States were not, of course, winning the war and, as the task force was gradually withdrawn from Phuoc Tuy, those temporarily left behind at the Dat grew bored and occasionally bitter. Still, when the Australian flag was hauled down for the last time at the base in November 1971, it was done with a ceremony which recalled the pride and discipline which helped make Australian soldiers dangerous opponents of their enemies in Vietnam.

Lowering the Australian flag for the last time at Nui Dat, South Vietnam. It is 7 November 1971 and NZ Regimental Policeman Private Tai Whatu, and Australian Regimental Policeman, Private John Skennar lower the Australian, 4RAR and RNZIR flags for the last time. collection/C37046